Sailor’s role in the birth of Israel

In My View

By Dr. Rafael Medoff

Issue of May 1, 2009 / 7Iyar 5769

His neighbors don’t know it, but on the quiet, palm tree-lined streets of Port Saint Lucie, the Mets spring training headquarters on the South Florida coast, lives an unsung hero of the fight for Israeli independence.

Jeno Berkovits, 90, was one of the gutsy American veterans of World War II who, instead of taking a well-deserved rest after returning from the war against Hitler, chose to sign up for a tour of duty in another war. He is among the dwindling group of American veterans of the battle to create Israel. On the eve of Israel’s 61st birthday, he agreed to his first-ever interview about those days.

Berkovits came to the United States from Hungary with his family in 1930. They settled in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, and Berkovits attended the Boys & Girls High School of Brooklyn. Lena Horne was a classmate; Isaac Asimov was one year behind them. “But what happened to a lot of boys in those days happened to me too,” he recalls. “My family needed me to help make ends meet, so I dropped out of school and went to work alongside my father in a factory making neckties.”

When America entered World War Two, Berkovits became a Merchant Marine. He spent the next five years on ships in various locales from the California coast to the Caribbean to Europe. The world war finally ended, but in British Mandatory Palestine a Jewish war raged. Home for less than a year when “I read in the newspaper one morning that a group called the American League for a Free Palestine was looking for sailors,” Berkovits says. “They wanted us to help bring Holocaust survivors to Palestine. How could I not go?”

The League, better known as the Bergson Group, was a political action committee that used full-page newspaper ads, rallies, and lobbying in Washington to mobilize support for creating a Jewish state. Now the

League was opening a new chapter in its battle. In late 1946, it had purchased a 150-foot yacht that it named the S.S. Ben Hecht in honor of the journalist and screenwriter who was one of the Bergson Group’s leading members, and began outfitting it in Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal.

“They interviewed me in their office in Manhattan, and soon afterward called to tell me I was accepted to join the crew,” Berkovits recalls. “Officially I was listed as a Messman, someone who serves food, but in practice almost everyone in the crew had to do all kinds of things.”

On December 26, 1946, the Ben Hecht sailed for France with a remarkably diverse crew of volunteers. “We had 20 men, with 20 different reasons for joining up,” Captain Robert Levitan said later. One was Walter “Heavy” Greaves, a beefy, tattooed professional sailor who survived three torpedo attacks during World War II. Shaken by a postwar visit to a Displaced Persons camp, Greaves took note when he read “that the Jews wanted a state of their own.” He thought to himself, “Why not, goddamit?,” and signed up for the S.S. Ben Hecht.

Another was Walter Cushenberry, a tall African-American in his thirties, with whom Berkovits became particularly friendly. “As a black man, he knew what it was like to be kicked around, and he didn’t like seeing the Jews get kicked around,” Berkovits said. “We had a crew member who was Irish Catholic and hated the British. We had a Jewish crewman who was religious and put on tefillin every day, and there were others, like me, who weren’t so religious but just wanted to help the Jewish cause.”

There were also two young Norwegians, Haakom Lilliby and Erling Sorensen. “They didn’t speak much English and nobody knew quite why they were there,” Berkovits says, “but when the engines broke down, they worked 24 hours straight to get us going again.”

In Port de Buc, France, the ship took on six hundred Jewish refugees. Conditions on board were difficult, but food was never in short supply, thanks to the two thousand pounds of kosher salami donated by a Bergson Group supporter. “It seems to me that we had salami sandwiches every single meal,” according to Berkovits. “But nobody complained.”

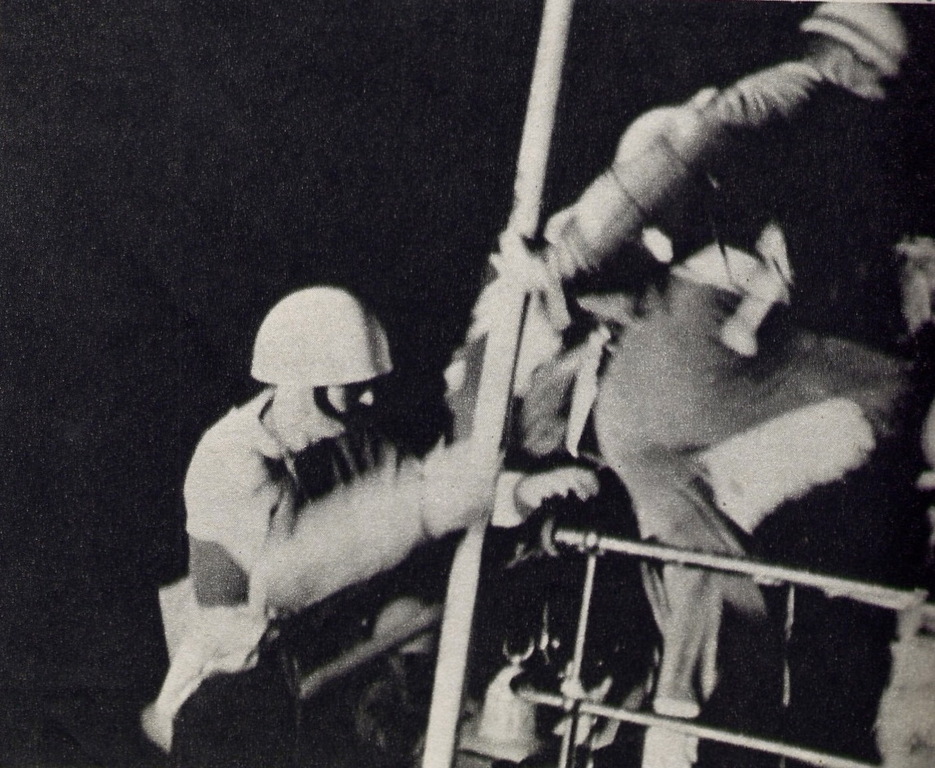

On March 8, everything changed. “That afternoon, I happened to be stationed on deck, at the steering wheel,” Berkovits relates. “I still remember how good it felt –– how the air smelled different as we got close to Eretz Yisrael. We were less than 10 miles from the coast of Tel Aviv, when three British destroyers approached and a British patrol plane circled overhead. I grabbed this flag, it had a big Jewish star on it, and hoisted it up the mast to show them that we were proud to be Jews fighting for our land.”

British soldiers wearing red berets — “we called them ‘red devils’” —

jumped aboard. They shoved Berkovits aside and quickly took control of the ship. The crew and the passengers were brought to a detention camp in Cyprus where they would end up staying for more than a year, until after Israel’s creation in May 1948.

Dealing with the American crewmen was a more delicate question. While the British government weighed what to do with them, the Americans were taken to the Acre Prison fortress, where they were jailed alongside members of the Irgun Zvai Leumi and Lehi (Stern Group) underground militias. The British authorities would soon regret that. The Irgun men had been planning a break-out, and only one obstacle remained: how to take photographs of the would-be escapees in order to make false identity cards so they could get past British roadblocks. Captain Levitan who had smuggled a small camera into the prison solved that problem.

To London’s dismay, the detention of the Ben Hecht crewmen became a lightning rod for criticism from members of Congress, the American press, and the U.S. Jewish community. After holding the seamen for a month, the British decided they were more trouble than they were worth, and put them on a ship bound for New York.

But even after returning home Berkovits and his colleagues continued to make trouble for the British. As a result of the contacts he made with the Jewish underground members in Acre, Berkovits and fellow crewman Harry Herschkowitz established an “American Friends of Lehi” organization. Operating out of a small office in Manhattan, they raised funds and published a newspaper called “Freedom” which sought to rally public support for ousting the British from Palestine.

Today, Berkovits, one of three surviving members of the Ben Hecht crew, recalls the events of 1946-1947 with satisfaction. “I am proud of the small role that I played in what happened back then,” he says. “We did what we could, and we did the right thing.”

Dr. Medoff is director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and author of blowing the Whistle on Genocide: Josiah E. Dubois, Jr. and the Struggle for a U.S. Response to the Holocaust.

45.0°,

Partly Cloudy

45.0°,

Partly Cloudy