Survivor déjà vu: Renewed antisemitism, war

For months, the news has been filled with some chilling events aimed at the Jews: Kidnap, rape, torture, murder and war with a brutal enemy that hides in schools, hospitals and an endless network of underground tunnels. And from around the globe, rising antisemitism on college campuses, protests and marches down city streets, news broadcasts in the media — not to mention getting a thumbs up from global agencies like the United Nations and the Hague’s International Court of Justice.

For Holocaust survivors, all of this seems an eerie sense of déjà vu, taking them back eight decades to a time everyone thought was ancient history.

The three who spoke to JNS are following news of Israel’s war against Hamas closely — a war that came out of pogroms on Oct. 7 inside its borders.

“When I think of the captives being burnt alive, I think of my mother and brothers whose bodies were burnt in crematoria,” says Rena Quint, an 88-year-old survivor living in Jerusalem. “And when I think of the hostages living on half a pita and a bit of rice, I remember how we nearly starved and how towards the end in Bergen-Belsen, we drank water from puddles. I completely understand how they must feel.”

Since Oct. 7, survivor Bronia Brandman of Brooklyn, N.Y., has kept her computer tuned to the news of the war in Israel. “I can see how the media is really giving Israel a bad name and social-media platforms, too,” says the 93-year-old. “They’re totally distorting what’s happening there. It’s a myopic view that reminds me so much of the Nazis, like a repetition. And, if the Jewish bigwigs think they can close their eyes and it will go away, they are very much mistaken.”

David Frenkel, a survivor living in Jerusalem who is a 58-year veteran of the Israel Defense Forces, as well as a retired judge, is equally concerned. “In schools with tunnels under them, our soldiers found books including the ideology of Hitler,” he says. “Every country has to stand up against this horrible hatred; it needs to be stopped before it goes any further.”

And although the Nazis took years to develop their policy of mass destruction of the Jews, he adds, “the kind of inhuman cruelty we’re seeing now against men, women, children and even babies sounds very familiar.”

These survivors are also watching with concern the steep increase in antisemitism around the world, a phenomenon that transports them back to their own childhoods.

“In 1933, Jews were already experiencing restrictions, and in 1938, you already had Kristallnacht,” says Quint. “Today, there are Jews who are afraid to wear a Magen David” (a “Star of David”), and, she notes, she read that “nearly 20 percent of people in New York say they believe Jews caused the Holocaust.”

This triggers early memories for the mother, grandmother and great-grandmother.

Born in 1935, the only thing Quint recalls of her first three years was her two big brothers pulling her on a sled in their hometown of Piotrków, in central Poland. The happy childhood ended on Sept. 5, 1939, when after the country was invaded by German Nazis on the first of the month, they rolled into her town in tanks and airplanes, throwing grenades into Jewish homes. When they were rounded up in the town synagogue, a stranger shouted at her to run and she did, never seeing her mother or brothers again.

Eventually reuniting with her father and uncle, she was disguised as a boy and put to work with them in a glass factory until they were shipped to Bergen-Belsen, where a series of women took her under their wings.

Quint was on a death march at the time of liberation and then sent to Sweden to recover from typhus, eventually landing in America, where she was adopted. “My life ended at 3 and began again at 10,” she says. In 1984, she moved to Israel with her husband and children.

Of the more than half a million Hungarian Jews who were murdered, 100 of them were Frenkel’s family. “So when some Germans came to ask for forgiveness, I said I don’t have the right to grant forgiveness on behalf of the 6 million,” he says. “No one gave us power of attorney to do that.”

Before his ninth birthday, Frenkel’s childhood took him from his native Hungary through the Budapest ghetto and to Bergen-Belsen after most of his family perished in Auschwitz. He was 9 in the fall of 1945, on his way by himself to pre-state Israel through the Youth Aliyah program.

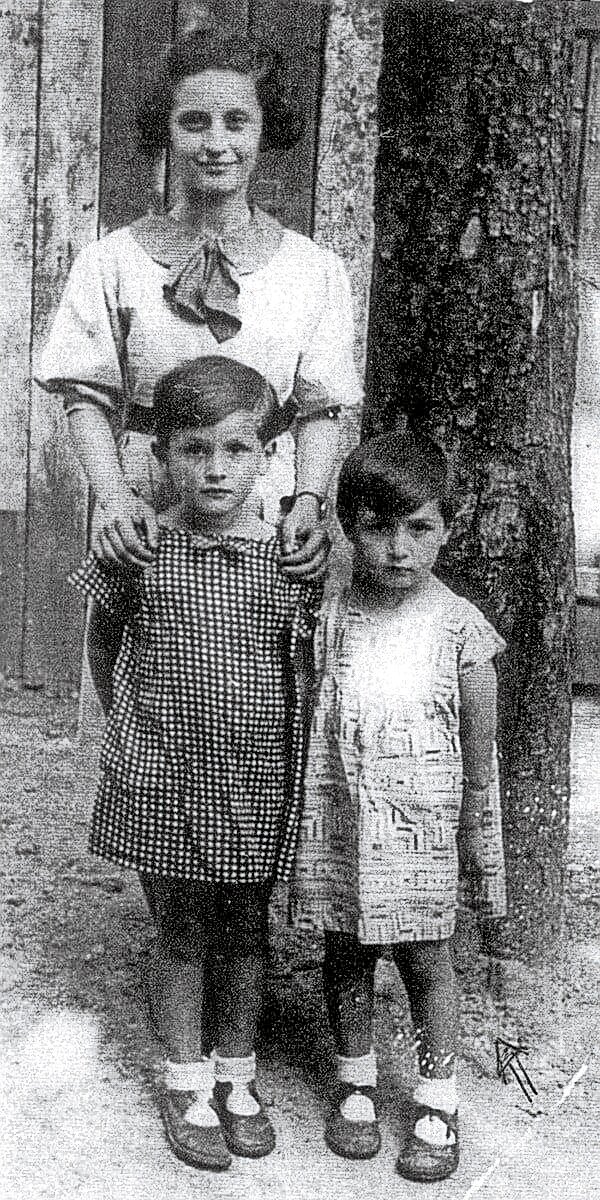

Like Quint and Frenkel, Brandman grew up fast. She was 8 when the Nazis invaded her hometown of Jaworzno in southern Poland. “We heard their booming, threatening voices — just to hear those voices made your blood curdle,” she recalls. “We knew that life would never be the same.”

From a family of eight, only she and one brother survived Auschwitz. One moment particularly haunts her: Staying with a sick sister in the camp infirmary, she was warned that all patients would be killed the next day. Though she felt terrible leaving her sibling, Brandman fled the infirmary. Like Quint, she, too, was sent on a death march before liberation.

Brandman did not speak of her Holocaust experience for 50 years, nor did she really laugh for 25. “The Nazis left me without any tears,” she says. In the end, she and the one brother were among the 17 Jews who survived the war out of the 2,000 who once lived in their hometown. They made it to America in 1950, where she married and had a family.

From this, Brandman has a theory explaining why antisemitism keeps resurfacing: “I think people have that streak in them always, and when it’s unveiled, we’re scapegoated again and again.”

Of course, survivors like these are increasingly a rarity: Of the 3.5 million alive at liberation in 1945, an estimated 250,000 remain today as International Holocaust Remembrance Day draws near on Jan. 26-27.

One of them is Sheryl Ochayon’s 88-year-old mother, who was hidden for two years by non-Jewish friends in southeastern Poland near today’s Ukrainian border. “She’s very disturbed by what she’s seeing in the media about Israel; she finds it shocking and depressing,” says Ochayon, a project director at Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center. “And the more we learn about what happened in Israel on Oct. 7, the more it reminds her and all of us of the sadism of the Nazis.”

Ochayon adds that “the more we hear about the world looking the other way, including the Red Cross refusing to help the Israeli hostages, the more familiar this is sounding. It’s especially shocking to those of us who have always thought that the world is a much better place than it was in 1939.”

53.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

53.0°,

Mostly Cloudy