Soviet Jews learned to ‘read between the lines’

You shouldn’t judge Soviet Jewish homes by their book covers, yet their bookshelves often contained the only clues that they were Jewish homes.

The overwhelming majority of post-World War II Soviet Jews were not observant and lacked access to religious objects like mezuzahs. So books — often secular ones — identified homes as Jewish, according to Marat Grinberg, professor of Russian and humanities, and comparative literature chair at Reed College in Portland, Ore.

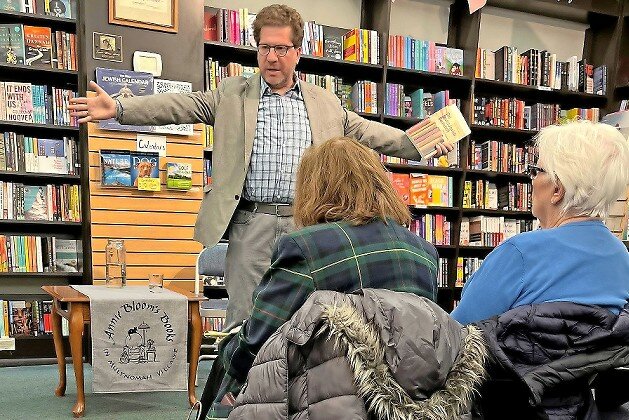

“Certain books in their bookcases were codes and secret language which Soviet Jews shared with one another,” Grinberg, author of the newly published book, “The Soviet Jewish Bookshelf: Jewish Culture and Identity Between the Lines,” told JNS.

Growing up in Ukraine, Grinberg was already “quite obsessed with everything Jewish” at age 12 or 13, as Jewish centers of learning were re-emerging. He began learning Hebrew and read about Jewish history, religion, philosophy, literature, politics and Zionism “voraciously,” including many 20th-century classics of Jewish thought in Russian translation.

In 1993, when Grinberg was 16, his family emigrated to the United States. Their bookshelves were packed “into a few tight boxes and bundles,” he recalled. “When we came to the States, I desperately wanted more Jewish education.”

He studied in the joint Columbia University-Jewish Theological Seminary program, where he was surprised to learn Jewish classmates and German professors alike knew nothing about German Jewish writer Lion Feuchtwanger, whom Soviet Jews lionized.

That planted the seed for the book about Soviet Jewish bookshelves, which “reveal that Soviet Jewishness was much more than an empty sign or only the sign of victimhood and persecution,” Grinberg wrote in the book.

So what does a scholar who studies other people’s bookshelves (and who would later earn a doctorate at the University of Chicago, where he wrote on Jewishness in Russian poetry) have lining his own walls? Some “contain the ingredients of the Soviet Jewish bookshelf,” replied Grinberg. Others have Russian classics, 20th-century Russian and German poetry, Holocaust literature, Hebrew and Yiddish Jewish books, and volumes on cinema and scripture.

As Grinberg is working on a new book about Jewishness and the Holocaust in Soviet and Eastern European science fiction, many of his shelves are packed with books by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky — Soviet brothers who wrote science fiction—by the Polish sci-fi writer Stanislaw Lem and by U.S. science-fiction writer Philip Kindred Dick, or PKD.

The key idea of the book is borrowed from the German-American Jewish thinker Leo Strauss, who wrote about “reading between the lines,” Ginberg told JNS. That kind of inventive and sophisticated reading was “necessitated by living in a totalitarian or authoritarian society like the Soviet Union,” said Grinberg.

• • •

Soviet Jewish bookshelves had explicitly Jewish books, such as commentaries on Sholem Aleichem or Feuchtwanger novels, while other volumes approached Judaism from an atheistic, anti-Zionist or antisemitic perspective.

“These required crossing out many lines and reading between the lines,” said Grinberg. That sort of reading, he writes in his book, at times “presented a subversive intellectual game and a hunt for knowledge. Some writers wanted to be read between the lines, and others might have resisted it.”

An example in his book of Soviet readers gleaning valuable information from anti-Jewish books is also a personal memory. In fifth or sixth grade, a Jewish classmate and friend showed him “in secret a slim paperback he found hidden in the bookcase at home.” The volume was a copy of Trofim Kychko’s 1963 book “Judaism Unadorned.”

Kychko was alleged to be a Nazi collaborator, and the book, published by the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, was antisemitic and anti-Zionist.

The friend loaned Grinberg the book, and from the start, he was “genuinely repulsed” by what he read.

“From what I recall, I did not question the accuracy of Kychko’s sources — what seemed to be bizarre Talmudic titles and Hebrew terms — but the hateful suppositions he drew from them,” he wrote in the book.

Grinberg tore it up and threw it out — “the only time in my life I have ever done anything like that with a book,” he wrote. When his friend asked for the book back, he told him what he had done, and the friend asked him in disbelief how he could have done such a thing. “It was still a Jewish book! We could learn something from it,” the friend said.

Indeed, the book had a map of biblical Israel and stories about “good” Jews like Spinoza and certain Yiddish writers, he realized.

“Kychko proclaimed, ‘Scientific criticism has long debunked the indisputability of the truths of Torah and Talmud. Yet, throughout centuries, religious Jews were educated according to Torah and Talmud, seeing in them the main sources of wisdom … all knowledge about the world and the main laws of living’,” Grinberg wrote in the book.

“Cross out the first sentence and what remains is a statement on the pivotal role of the written and oral Torah in Jewish history,” he added. “Thus, it is futile to appreciate my friend’s reaction outside of the context of Soviet Jewish paradoxes, when any printed material that had the word Jewish in it was not to be bypassed, at times guiltily, ironically or indignantly by the Jewish reader.”

Soviet Jews brought caution and inventiveness to the ways that they educated themselves as Jews, Grinberg said: “It is these skills that they brought to the page as readers.”

In the book, Grinberg describes Soviet Jewish readers seizing upon any printed material with the word “Jewish,” with certain volumes only available on the black market or in specialty stores. There were even “book rations” that one could acquire with enough special tickets, which one would get, say, for turning paper goods in for recycling.

He writes in the book that his memories, “palpable and tactile, filled with the smells and textures of book spines and covers, shelves, bed stands, and suitcases that would be packed to the brim with the books during emigration,” inform the volume.

That, of course, is lost with the advent of e-readers.

“At this point, however, for me, it’s not crucial,” Grinberg told JNS. “As long as my students read, I don’t care if it’s an actual book or an e-one.”