Runaway bochur’s work may aid Covid research

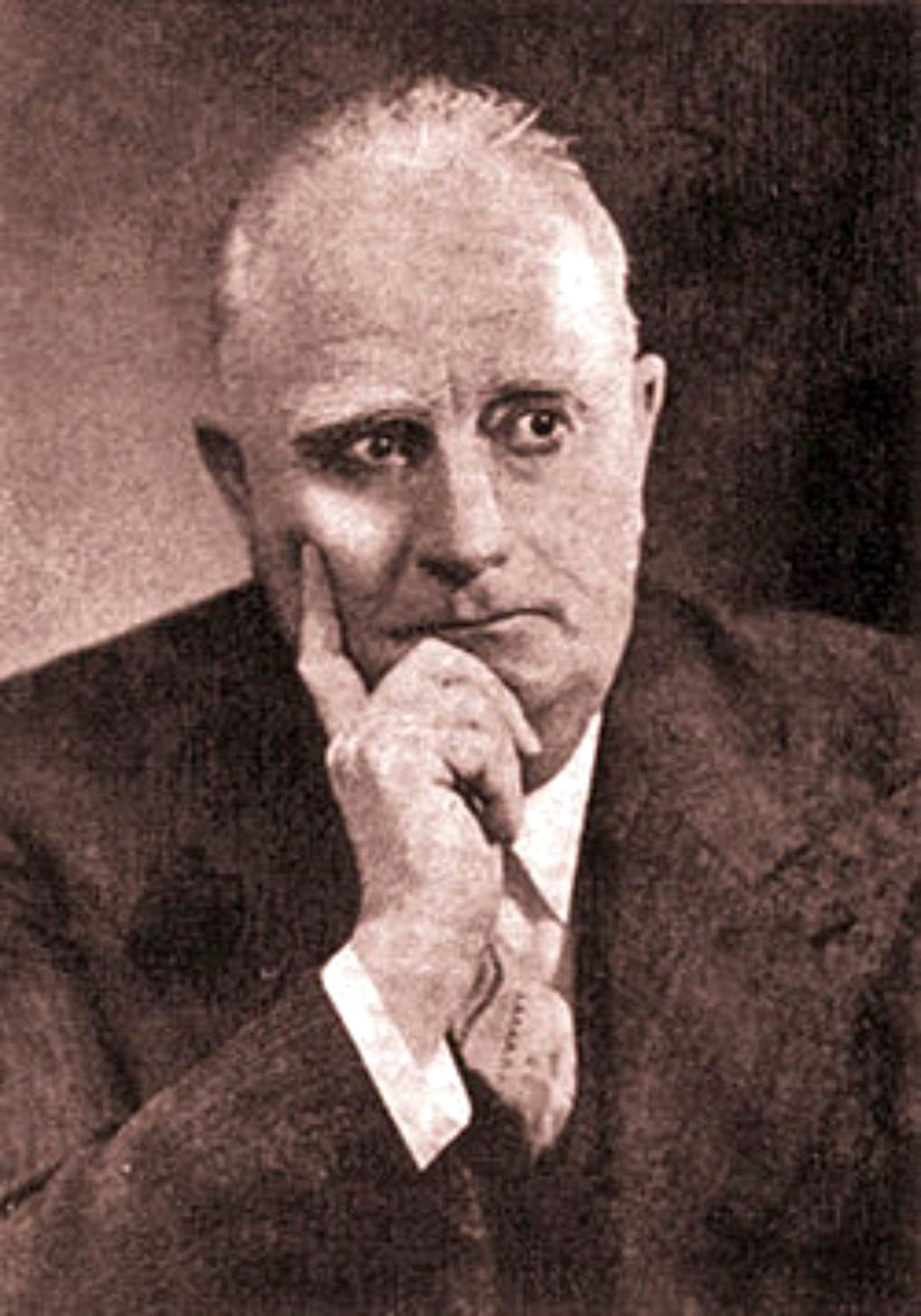

Shortly after emigrating to Israel in 1901, this Telz-educated orphaned son of a rosh yeshiva earned an unlikely nickname: “the crazy fly-catcher.” Israel Aharoni’s odyssey into the world of middle eastern zoology, long recognized in the scientific world with over 30 species named after him, is earning new attention for its potential contribution to COVID-19 research.

He was born in Vidzy, Belarus, as Yisroel Aharonovich in 1882. Like the Talmud sage Abaye, he tragically lost his father before he was born and his mother shortly thereafter. At the tender age of two he was sent to live with his grandmother Malka, who raised him in the family tradition of Talmudic studies at the Yeshiva of Telz, which left a deep imprint on young Yisroel, especially in terms of its languages and descriptions of the natural ancient habitat of the Jews in Israel and Babylonia.

Yet Yisroel yearned for a more scientific approach, and at 13 he smuggled himself out of the Russian Empire to study with Rabbi Dr. Armand Kaminka in Prague, and then briefly at Charles University, focusing on Arabic philology and zoology. An encouraging letter from Theodor Herzl motivated him to move to Israel, where he Hebraized his name to Aharoni, taught languages, and continued his passionate study of the fauna of the Holy Land.

Over the next two decades his amateur search for animals, birds and insects mentioned in the Torah and Talmud became his full-time occupation. He wandered throughout the Middle East, often unescorted through hostile areas (he was once nearly hanged by Turks who suspected him of being, of all things, an Italian spy). Among his publications is “Torat ha-Hai: The Torah of Life,” an appropriately named and frequently reprinted zoology textbook for young students.

His most unlikely contribution to science came in 1930, when he journeyed to Aleppo, Syria, in search of the elusive rodent Mesocricetus auratus known to locals by its Arabic name “Mr. Saddlebags,” a reference to its habit of stuffing its cheeks with food. The burrowing rodent was first identified in 1797 and named in 1839 but rarely seen since then.

Aharoni and a Syrian guide named Georius Khalil Tah’an went door-to-door asking farmers if they had seen Mr. Saddlebags (encouraging some incredulous responses) before identifying a likely farm. With the permission of the local sheik (but not the farmer), Aharoni and Tah’an dug up the freshly planted field to a depth of eight feet before they discovered their prize: a nest with a mother and her ten pups. Aharoni would eventually give the species the Hebrew name ogen. In English, we know the animal as the common hamster.

Now widely domesticated as a pet, the Syrian or Golden hamster is as antisocial as it is fecund: the females go into heat every four days, and once pregnant, have an incredibly brief gestation period of 16 days, with litters of some ten pups. The survival of the young, however, depends largely on the mood of the mother — when stressed, she is likely to consume them, which is precisely what happened to one of the young before the horrified Aharoni could separate the mother from her litter.

Tah’an euthanized the mother, a hasty decision which complicated matters because Aharoni had to raise the pups himself, feeding them with an eyedropper in his Jerusalem laboratory. Highly territorial, the surviving hamsters bristled at their captivity and five of them engineered a mass escape by chewing through the wooden box that Aharoni had placed them in, fleeing the laboratory through a hole in the floor. Then one of the remaining males ate his sister before Aharoni could arrange for more appropriate hamster accommodations.

Ultimately, Aharoni was able to breed the survivors, whose descendants now live in hundreds of thousands of children’s bedrooms as pets. More significantly, he donated descendants of the “Eve” hamster to tens of international scientific labs for research, as their immune responses have proven to be remarkably similar to that of humans, prompting research in a wide variety of illnesses for almost a century.

Researchers in 2019, working with new gene editing technology, discovered that the potential for Syrian Hamster research is even greater than scientists had previously realized, prompting a follow-up study recently published by Oxford University Press and the Infectious Diseases Society of America that specifically proclaims the utility of this animal for COVID-19 research.

Thus the 1930 discovery by a young Israeli scientist, once a former runaway yeshiva bochur, is proving to be instrumental in the fight against this great pandemic.