Rabbi Billet: Yeshiva College cannot fund and recognize LGBTQ club

There has always been a tension at the core of the concept of Yeshiva College. A Yeshiva is an institution committed to the yoke of heaven and to the observance of the Torah’s commandments, while a College in the USA is place of free intellectual inquiry and freedom of expression.

For many of us who attended Yeshiva College in the late 1960s and early 1970s, what the institution meant for us lay in that oxymoron at its core. It symbolized for us the unresolvable complexity of what it meant to be Orthodox Jews in America. We believed in free inquiry and free expression, but as Orthodox Jews, we also felt that the Torah limited our expression. Yeshiva College was a place where we could deeply expand our intellectual horizons, open our minds, and yet remain fully part of the world of the Yeshiva. It was a paradox and a dream, and it was a place that nourished our minds and our souls.

Today, the challenges of the paradox of Yeshiva College are all over the news in a painful controversy over expressions of LGBTQ identity and well-known Torah norms that cut against this.

In over 40 years in the rabbinate, I have been moved by the plight of gay Orthodox Jews. I have worked hard, alongside many other compassionate rabbis, to reconcile parents with their children, and to make the Orthodox community as welcoming as possible to gay Jews, while also acknowledging a painful but binding halakhic reality.

I understand the plight of the students, and I understand the predicament that YU is facing. It is a difficult situation and we must all approach it with compassion for the positions on all sides, and pray that Hashem grants wisdom and strength to all involved.

• • •

The current situation at YU has extended beyond this painful and challenging sphere into a broader and more fundamental question that cuts at the core of what Yeshiva College is and what the institution has meant to so many of us who have spent our lives trying to straddle the difficult boundary between Orthodoxy and modernity.

The current controversy arose when the LGBTQ student club sued YU in court over its refusal to fund the club. YU welcomes students of all sexual orientations to the college, but it viewed the issue of funding the club as a breach of the norms of halakha.

In a June ruling, the State Supreme Court found that Yeshiva was not incorporated as a religious institution but as an educational one. Therefore, it must abide by New York City’s human rights laws, which do not allow discrimination based on sexual orientation. YU is now appealing this ruling, on the grounds that it has far broader implications for the ability of Yeshiva College to retain its character as an Orthodox Yeshiva.

While I am deeply pained over the specific issue that has led to this broader controversy, an issue that has been very close to my heart as a community rabbi who has helped reconcile many families and who has advocated for compassion and inclusion, I support YU in its fight to ensure that it has the legal rights to retain its Orthodox character.

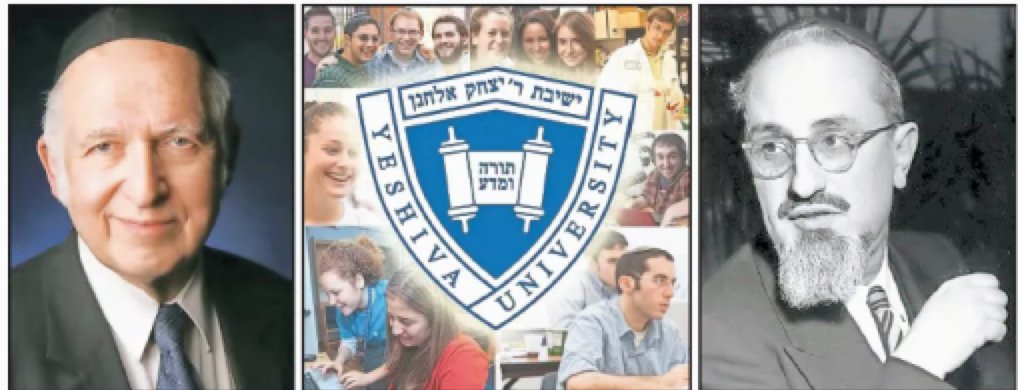

In fact, I fought for this broader issue in the academic year 1969-70, at a time when YU made a decision that I and many of my fellow students and our beloved and honored rebbeim — including Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (the Rov) and Rabbi Aharon Lichteinstein — deeply opposed. I believe this historical moment lies at the root of the broader legal issue in the current controversy. I think it’s worth sharing some of that history.

• • •

In 1969-70, when I was a student at YU, the Concerned Student Coalition clashed with the YU administration after we had discovered that two years prior, in 1967, Yeshiva University had changed its charter and turned the entire institution including the three undergraduate religious divisions into nonsectarian divisions.

YU did this for practical and understandable purposes. New York State’s Bundy Funds, which provided essential funding for independent colleges, were no longer available to religious institutions. To obtain these crucial funds, YU had to reframe its mission with a focus on the College, rather than the Yeshiva, side of the paradox.

We students were aghast when we learned of this change. We objected to the notion that the Yeshiva we were attending was no longer sectarian. It misrepresented what we enrolled to attend. For us, the Yeshiva side was as important if not more important than the College side of the paradox. We could only condone a Yeshiva College that lived in the tension.

We also felt that this was simply dishonest. We were not politicians or leaders tasked with ensuring a financially viable institution in a tough economic setting. We only saw that the dream we were trying to live — that paradoxical dream — was at stake.

Things came to a head that year around the celebration of the Chag HaSemicha, one of the biggest events associated with the Yeshiva, celebrating the ordination of graduates of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS).

• • •

With the support and with the full participation of the Rov and Rav Lichtenstein, we organized a demonstration of the Yeshiva College, Stern College, and RIETS student body to be held concurrently with the Chag HaSemicha. We were careful that none of our signs or statements be ad hominem or insulting. The basic content was advocacy to save the essence of what Yeshiva College had always been, a place of Torah study connected to a full College program.

In the wee hours of Saturday night just before the events at Yeshiva University were to occur, the Rov asked us to call off the demonstration and to trust him. He would be speaking at the Chag HaSemicha and he would advocate for our cause in that speech.

We were unable to fully honor his request at that point, because the plans for the protest were too far underway and had taken on a life of their own. Those of us who were his students did not participate in the demonstration, however, and went instead to hear his speech.

On that Sunday 1500 men and women, all students in various divisions of Yeshiva University, attended the demonstration and protested respectfully and behaved in ways that complied with the expectations of the character and behavior of yeshiva students.

Although he had asked us to call off the demonstration, when the Rov spoke, he referred to the demonstrators, as “the finest boys and girls I have ever met. This is a demonstration for Torah. I identify with them one hundred percent!”

We, his students, were deeply moved by this.

Ironically the current incorporation of YU that led to the ruling YU is now appealing in court seems to be a function of what Yeshiva did in 1967 when it became nonsectarian. One might suggest that this ruling is a corollary of exactly what the Concerned Student Coalition, The Rov, and Rav Aharon Lichtenstein were trying to prevent when we became aware of it in 1969-70.

Although the issue that triggered the current controversy is deeply painful, Yeshiva College is right to rectify that mistake that was made back then. It owes a principled stand on the legal matter to the undergraduate students who have chosen to attend College at an Orthodox Jewish institution.

At the same time, the YU administration and the leaders of American Orthodoxy more broadly must continue to have ongoing conversations, filled with compassion and empathy alongside commitment to halakha, to make room for all our deeply loved children, young adults, and adults, especially when halakhic norms lead to painful realities.