Mendelevich’s Jewish war defeated communism

How ironic that a published history of the struggle to liberate Soviet captive Jewry begins with two words — Yosef Mendelevich.

“When They Come For Us We’ll Be Gone,” by the skilled journalist and essayist Gal Beckerman (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), describes the struggle between Judaism and community that Mendelevich personified, and which defined a generation of Jewish youth both in the Soviet Union and America.

In 598 pages, Beckerman tells of the titanic struggle that would ultimately defeat communism. He covers those at the grass roots level who gave of themselves to help liberate hundreds of thousands from the shackles of communist tyranny, and features such personages as Avi Weiss (see story on page 1), Jacob Birnbaum, Glenn Richter and Abraham Joshua Heschel, who helped to catapult this issue to the front pages.

Yet it was Mendelevich who came to symbolize the Jewish religious element in direct combat with Marxist-Leninist communism on both ideological and physical levels.

“Mendelevich was a shy boy with pale, pimply skin and thick horn-rimmed glasses,” writes Beckerman of the face of the struggle. He was born in post-war 1947, into an ash heap from World War Two, with a Jewish community in physical waste from the murderous struggles that resulted in the destruction of over six million Jews.

• • •

This Jewish community was betrayed by those who it viewed somewhat favorably before 1939.

In his 1958 study, “Masters of Deceit,” FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover goes into great detail demonstrating the communist betrayal of East European Jewry in helping to blindside them to what was to come at the murderous hands of the Nazis. In a chapter titled, “The Communist Attack on Judaism,” Hoover states:

“The third communist propaganda claim, that of rescuing Jews from Nazi extinction, is also a deception. In the first place, for two years prior to the Nazi invasion of Russia, when Moscow was allied with Berlin, there is no record of any Soviet protest against the Nazi slaughter of Jews, so far as is known. The good-neighbor policy between the communists and the Nazis, initiated by the Stalin-Hitler pact, is clearly established by the following report sent by the German Foreign Office, where it came to light after the war. … ‘The Soviet Government is doing everything to change the attitude of the population here toward Germany. The press is as though it had been transformed’.”

Hoover continues by stating, “Then, too, the silence of the Soviet leaders on the outbreaks of Nazi anti-Semitism completely misled Eastern European Jews as to the real character of the Nazi threat and hence, some two million Russian and East European Jews made no attempt to escape the Nazis during the early months of the German invasion of Russia. And even after the Nazi onslaught, there was a shocking failure on the part of the Soviets to reveal Nazi atrocities against the Jews.”

“Not only did the communists in the Soviet Union fail to make any effort to save Jewish people during the war, they showed no concern over their fate,” Hoover wrote.

Furthermore, the director notes that concurrent with the Holocaust, the communist attitude toward Zionism reflected policies and actions that would lead to mass suppression, targeting Jews who wished to identify with and later to emigrate to the Jewish state.

• • •

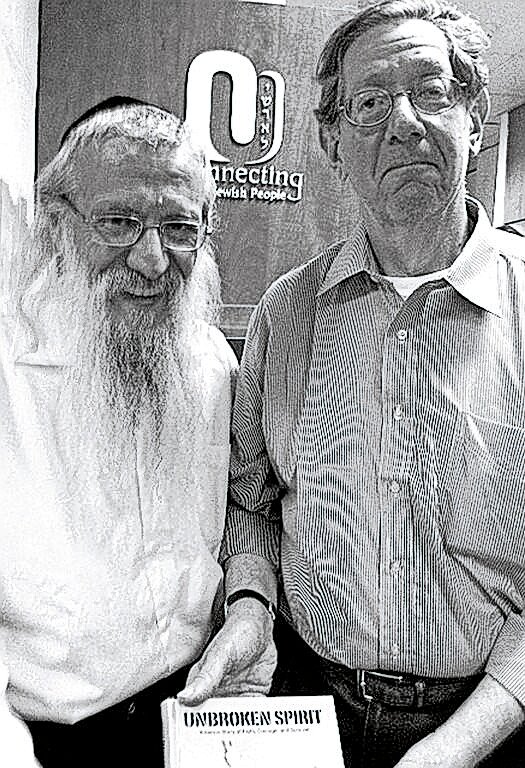

This was the world into which Yosef Mendelevich and his contemporaries were born, a world hostile to both Judaism and its concurrent Zionist ideology. In this world of communist oppression, Mendelevich was to experience severe cruel persecution and eventual brutal imprisonment, horrific experiences described in great detail in Mendelevich’s recently translated, “Unbroken Spirit: A Heroic Story of Faith, Courage, and Survival” (Gefen Publishing, 2012), translated by Benjamin Balint.

Mendelevich’s work is “an extraordinary testament. It tells us that nothing can kill the human spirit,” Beckerman says. “Even living in a totalitarian regime, where his basic rights were denied, Mendelevich managed to rise to great heights of bravery and faith. He recounts his story beautifully and powerfully. It is impossible not to be moved by the resilience of his Jewish soul.”

It was to this Jewish soul, the spirituality that frames Mendelevich’s whole existence, that most impressed me when I met him last year in Jerusalem.

This sentiment is reflected by Mendelevich in the following:

“Someone who called to urge me to publish this book accurately observed:

‘The value of your book lies in the fact that you have so faithfully and consistently continued to live the life you began all those years ago.’ He was right. If I were to honestly ask myself, ‘Are those values you believed in — the people of Israel, the land of Israel, and the Torah of Israel — still significant for you?’ I would answer, ‘Yes, yes, yes !’

“Not only have I not veered from the path on which I originally set out, but I have progressed along it. I have studied a great deal of Torah and, aware of how much I do not know, I wish to learn much more. I have endeavored to act for the good of the Jewish people here in Israel, and wish to do so much more. It is for this reason that I feel privileged to address Jews all over the world.”

• • •

In a special message for this essay, Glenn Richter, one of the premier leaders of the Liberate Soviet Jewry movement, writes the following tribute to his friend:

“My respect for Yosef has grown over the past 41 years since we campaigned for his release from the brutal gulag. He remains clearly focused — that the plot to hijack a small plane to fly to freedom, though doomed, was the strongest possible expression of the desperation of Soviet Jews to exit to Israel, that it galvanized Jews across the USSR to demand their freedom and free world Jews to support them — and we can never forget that sense of abiding solidarity.

“Yosef realizes that he remains a role model, and is willing to shoulder the burden, for those who wish to take their Jewish identity seriously and put practical application to their beliefs. His book shows how he thought each step of belief and then acted upon it. Sometimes the appellation ‘inspiring’ is used too loosely. In Yosef’s case, that’s just the beginning.”

At the conclusion of an interview in the OU’s Jewish Action magazine, Bayla Sheva Brenner asked Mendelevich this question: “As a Jew who believes in hashgachah pratis, why do you think G-d deemed that Yosef Mendelevich be born in communist Russia and find a way to blossom as a Jew in that environment?”

Mendelevich replies: “I have no explanation, but I am thankful to the Ribbono Shel Olam for having selected me for this mission. It is the reason I wrote my book, to show how, with the help of G-d, it is possible for even an assimilated Jewish boy living in communist Russia to find his Jewish soul. It is my hope that the next generation of Jews will read the book and think, ‘If a simple Jew like Yosef Mendelevich could do it, I can too.’”

Let me conclude by stating that we all can only respond with a hearty Amen to these heartfelt sentiments. As a student of Marxist communist ideology, I can only marvel at the fortitude that Mendelevich represents to all of us.

Our faith deserves this commitment and we, in turn, must dedicate ourselves to further observance to the tenets of our faith in G-d, equally both in ethics and ritual.

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy