Kosher Bookworm: Liberty Bell and the Torah Connection

“Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof” are words that were read in last week’s Parsha Behar, chapter25, verse 10.

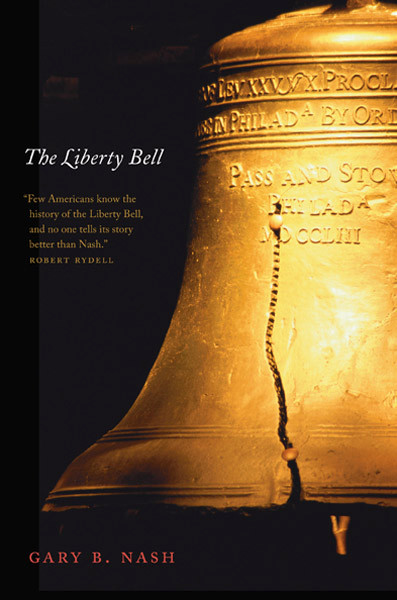

This very verse is inscribed upon the world famous American icon, the Liberty Bell located in Philadelphia. Its very theme speaks to the very ideological foundations of our republic, of freedom and political and economic equality for all.

In a recent dvar torah, Rabbi Mordechai Kamenetzky said, “Truth be told, these words refer not to a revolution or liberation, they refer to the mitzvah of ‘yovel’ – jubilee. Every 50 years, all Jewish servants, whether employed for only a six-year period or on an extended docket, and even those who desire to remain as servants to their masters, are freed. They return home to their families, and their careers of indenture are over.” Nevertheless, this verse was given new meaning in the minds of the planners of the Liberty Bell.

To those devout Christian leaders of pre-revolutionary Philadelphia, these sacred words represented for them and their people the hopes and aspirations for the better life that brought them and their ancestors to these shores from the despotic monarchies of Europe.

Having just celebrated Pesach Sheni and its theological echo of the festival of freedom, we would be well served to take a closer look at this American icon that carries so eloquent a tribute to the Jewish devotion and intense love for freedom.

George B. Nash, professor of history at UCLA, is the author of a beautiful book aptly titled, “The Liberty Bell” (Yale University Press, 2010) wherein he goes into great detail describing the plans, and personalities, led by Isaac Nash, as well as the pain that went into the erection of this bell back in the mid-18th century. To those devout Quakers who planned this icon, the use of the words to be inscribed upon it represented the fulfillment of a sacred religious obligation.

According to Nash, “These words from the Bible were freighted with social and political meaning. These were words that would take on new layers of significance in different eras, in different contexts, and in different parts of the world. Little did the bell’s commissioners know what lay ahead for this biblical verse.”

Nash speculates at what might have been in these people’s minds. ”What effect did they hope such an inscription would have? The surviving sources do not speak clearly to us about this. But, something is known, and much can be surmised. Norris had studied for two years in England and knew Hebrew, Latin, and French; he was also an avid student of the Bible.

“In consulting ancient texts, uppermost in Isaac Norris’ mind was the assurance of Pennsylvania’s bright future as a tolerant, fair-minded gathering of peoples from many parts of Europe, and Africa. Inscribed on this great bell should be words to inspire, words to hold people to founding principles.”

For us as Jews, these words take on much added meaning both in terms of the literary origin of the verse, the Book of Vayikra, and the political and civic meaning it has had upon our lives as loyal and proud Americans.

Further study of these words in the commentaries that I consulted all seem to focus on the Hebrew word for liberty, Deror.

In “Onkelos on the Torah, Leviticus” (Gefen Publishing House, Jerusalem) by Rabbis Israel Drazin and Stanley Wagner, we have the most extensive treatment on this verse in the English language.

“The commentators differ concerning the origin and meaning of the Hebrew ‘deror’, ‘liberty.’ Drazin and Wagner go into great detail tracing the of the translation and word origin, from the word meaning dwell, from the Hebrew, dur, to the name of a swallow that sings when it’s free, but dies when captive, to ‘dor’, generation. The term “freedom” of the Targun is derived from the Sifra and the Talmud [Rosh Hashanah 9a] and its meaning derives from Isaiah 61:1 and Jeremiah 34:8.

Both authors continue to follow this matter by referencing John Stuart Mill, and Isaiah Berlin from their works on the subjects of liberty and freedom, rather heady stuff for a chumash commentary. Yet, this reaching out to these great personalities speaks well of the authors as well of the sacred text itself.

From all the above we should all come to deeply appreciate this one fact, above all else. The greatness of our Torah and Tanach is that it speaks to us today as it spoke to Isaac Norris and his fellow commissioners of the liberty Bell in the 18th century, and… as it did to our ancestors in the desert from Moshe himself. How great is our inheritance and its legacy for all humanity.