Israel salutes America: 70 who counted in 70

On the occasion of the Jewish state’s 70th anniversary, the Israeli embassy in Washington, in partnership with the Jewish News Syndicate, celebrates 70 of the greatest American contributors to the U.S.-Israel relationship

Many of the people and organizations chosen for this acknowledgement will be readily recognized by readers of The Jewish Star, others less so, but their powerful stories build a collective history that reflects the broad base of American love and support for the Jewish state.

This week, The Jewish Star publishes the sixth part of a series that will cover all of the “70 who counted.”

Link here to all 9 installments:

U.S. Veterans 42 of 70

Crucial aid during the 1948 War of Independence came from American veterans of World War II, both Jewish and non-Jewish, who volunteered to fight to defend the Jewish homeland. Serving on all fronts, these volunteers were known as MACHAL.

During this time, the United States made it difficult for its veterans to fight for Israel. All passports were stamped with a warning that if one left the country to serve in the military of a foreign state, they could lose citizenship.

Indeed, many U.S. volunteers had their citizenship temporarily suspended when they returned. This highlights the effort and sacrifices of heroes who put their lives on the line for their Jewish brothers and sisters struggling for independence thousands of miles away.

Overall, American veterans made up a very small percentage of the Israeli forces, with one important exception: due to a severe lack of homegrown talent, the fledgling Israeli Air Force was essentially founded, run and staffed throughout the war by foreign volunteers, with a major U.S. contingent. There were so many Americans involved that for a time, English was the Air Force’s de facto language.

Similarly, the Israeli Navy was founded and commanded by American veterans. Paul Shulman, a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy with combat experience in the Pacific, served as its commander from 1948 through 1949.

Without these brave and heroic volunteers, Israel would have had no functioning air force or navy. Their dedicated service may well have determined the outcome of the war.

Lone Soldiers 43 of 70

With the establishment of Israel, two great transformations occurred in the lives of Jewish people: Jews from around the world could now immigrate to a Jewish state, and the Jewish people now had the power to defend themselves. Lone soldiers — individuals serving in the Israel Defense Forces whose families live abroad — embody both of these remarkable transformations.

Often driven by their commitment to Zionism and the Jewish people, thousands of young men and women come to Israel to serve in its military, enduring the hardship of not having a loving family nearby. While lone soldiers come from all over the world, a consistently large group comes from the United States, a testament to the vigorous support for Israel in American Jewish communities.

Lone soldiers serve throughout Israel’s armed forces, including special combat units and intelligence. In recognition of their status, they enjoy financial assistance and subsidized housing. Immigrating is difficult in any circumstance, and lone soldiers often arrive with limited Hebrew. Through sheer will, they often overcome adversity to become exemplary soldiers who inspire their Israeli-born colleagues with their idealism.

Lone soldiers fought in all of Israel’s conflicts. Tragically, a number of them have fallen in battle. Most recently, Sean Carmeli and Max Steinberg were killed in the Gaza operation in 2014.

While the loss of any young soldier is unbearable, there is an additional level of suffering for the family of a lone soldier so far away. To express their support, Israelis of all stripes took to social media to ensure that as many people as possible attended their funerals. On July 21, 2014, some 20,000 mourners accompanied Texan-born Sgt. Carmeli of the Golani Brigade to his final resting place.

In this way, ordinary Israelis acknowledge the sacrifices of lone soldiers. “It’s our national pride to come and support a family and a lone soldier — a person who made a decision, against all conventions and with Zionist motives, to join the best combat unit although he could have chosen a more comfortable life,” one funeral attendee expressed. “I am here to salute him.”

In 2009, the Lone Soldier Center was founded in memory of Michael Levin, a lone soldier from Pennsylvania killed in the Second Lebanon War. It currently serves more than 6,300 lone soldiers.

Harry S. Truman (1884–1972) 44 of 70

President Harry S. Truman will forever be remembered for his fateful decision to recognize the State of Israel on May 14, 1948. That decision came at a critical time, as the newly established country fought off genocidal attacks in its War of Independence.

Although America’s support for Israel is often taken for granted today, Truman’s decision was met with tremendous opposition from some of his closest advisors, as well as prominent sectors of the U.S. government. Secretary of State George Marshall told Truman that if he recognized Israel, Marshall would not vote for him in November.

Despite his profound admiration for Marshall, Truman did not waver. As he later recalled: “George Marshall … was afraid the Arabs wouldn’t like [our recognizing Israel]. This was one of the few errors of judgment made by that great and wonderful man, but I felt that Israel deserved to be recognized and didn’t give a damn whether the Arabs liked it or not.”

Raised Protestant in Missouri, Truman had Jewish friends, and even a Jewish business partner. Later, as a senator, Truman spoke on behalf of a homeland for the Jews in Palestine. This belief was founded in his affection for the Jewish people and in his knowledge of the Bible, which inspired a rational sympathy for the refounding of a Jewish homeland.

In May 1948, as the British Mandate neared its end, Truman’s cabinet was divided. Nearly all his foreign policy “wise men” were against recognizing the new nation, including Defense Secretary James Forrestal, George Kennan and Dean Rusk. They believed that it would obstruct American access to Arab oil.

But Truman decided to recognize the Jewish state, making his announcement just 11 minutes following Israel’s declaration. Reflecting on his support in its fledgling moments, Truman famously compared himself to Cyrus the Great, the Persian ruler who allowed the Jews to return to Israel and rebuild the Temple.

It was not electoral considerations, as is sometimes alleged, that motivated Truman — it was his religiously inspired and politically informed sense that the Jewish state would be a great boon to America and the world.

To the State of Israel and its international friends, Truman will indeed forever be remembered as a second Cyrus.

Sanford ‘Zalman’ Bernstein (1926–1999) and Roger Hertog 45 of 70

In 1978, Sanford Bernstein was a brilliant investor leading a high-flying, largely secular New York life. That year his father died, and Bernstein began deeper inquiries into the faith of his parents, with the help of a warm and learned rabbi, Rabbi Shlomo Riskin.

Bernstein did nothing halfway. In the years that followed, he began using his Hebrew name, Zalman, and committed himself to observance. He would later make aliyah to Jerusalem, where he died in 1999.

Bernstein’s spiritual quest led him beyond personal renewal. He devoted the final chapter of his life to invigorating Jewish intellectual life and practice. To that end, he created philanthropic organizations — the Avi Chai Foundation and the Tikvah Fund — devoted to advancing Jewish and Israeli causes, organizations and ideas.

Founded in 1984, the Avi Chai Foundation has been devoted to strengthening the Jewish people and attachment to the State of Israel, and to cultivating mutual understanding among Jews of different affiliations. It has invested more than $300 million in support of innovative projects. Its work in the former Soviet Union has been particularly vital in giving the gift of Jewish and Zionist learning and practice to communities that had been deprived of these during Soviet times. After Bernstein’s passing, his wife, Mem, continued his philanthropic legacy.

The Tikvah Fund was founded in 1992. Since Bernstein’s death, its efforts have been guided by his friend, business partner and intellectual comrade Roger Hertog. Hertog has been guided by the important insight that ideas matter for the future of the Jewish people and state.

The Tikvah Fund has been a veritable incubator of profound Jewish thought. Tikvah-funded journals, including Azure, Mosaic, the Jewish Review of Books and Ha’Shiloach, have brilliantly expounded pressing questions facing Israel and the Jewish people. Educational programs in America and Israel have allowed thousands of students to deepen their intellectual engagement with Judaism and Zionism.

In 2017, Shalem, Israel’s first liberal arts college, which has received generous support from Tikvah, held its first graduation ceremony. Hertog received an honorary doctorate for his devotion to the cause of humanistic education in Israel — a fitting culmination of the work that he and Bernstein set out to accomplish.

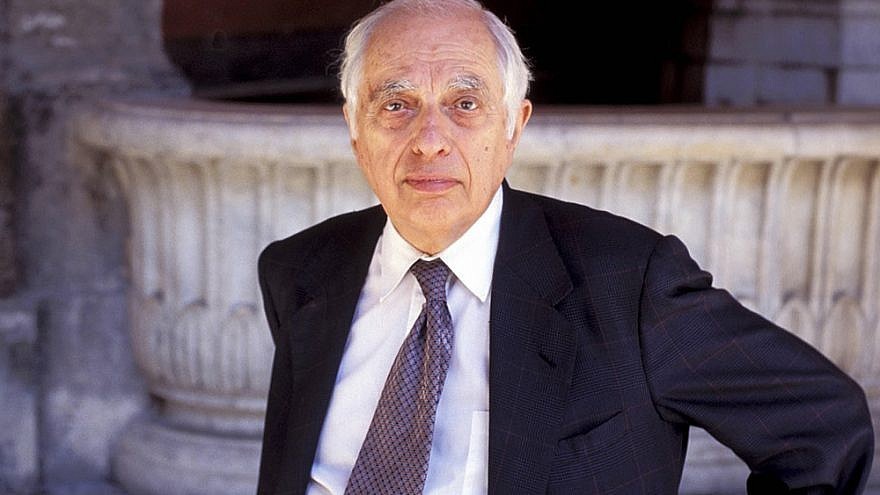

Bernard Lewis (1916-2018) 46 of 70

Bernard Lewis, who passed away over Shavuot at age 102, is known as an outstanding historians of the Middle East. Yet unlike many Mideast scholars, Lewis never combined his scholarly sympathy for the Arab and Muslim people of the region with antipathy towards Zionism and the Jewish people. Indeed, he was a lifelong Zionist and a friend to Israel.

While much contemporary Middle East scholarship has been ideological, Lewis is best known for his accurate and honest studies of the area’s people. Fluent in at least eight languages (including Arabic, Turkish, Persian and Hebrew), his studies remain a treasure.

Lewis has also proved a prescient scholar. In his 1976 essay “The Return of Islam,” Lewis predicted that a “clash of civilizations” was coming, anticipating the rise of radical Islamic theocracies. Similarly, his bestselling What Went Wrong?, written just before 9/11 but published afterward, explained these governments’ hostility toward the West and Israel.

Among more than 30 books and countless articles is Lewis’s definitive work, The Jews of Islam. It neither romanticized Jewish life under the Islamic governments pre-Israel, nor was it a mere polemic. Instead, it aimed to show what really happened: how Jews frequently lived under caliphs and sultans as useful and tolerated, though disfavored, subjects.

Raised in a middle-class Jewish home in England and educated at the University of London, Lewis was a naturalized American and taught for decades at Princeton. For more than 40 years, he spent the winter months in Tel Aviv, where he taught classes in Middle Eastern history and worked with budding Israeli scholars.

Throughout his career, Lewis mentored many of the greatest scholars of the Middle East and Israel, including Fouad Ajami, Martin Kramer, Harold Rhode and former Israeli Ambassador to the United States Michael Oren. In addition to his work on Arab history and culture, he offered fascinating reflections on Israel, particularly on how Jewish history helped the country maintain democracy despite the Jews having lacked sovereignty for 2,000 years.

As an honest scholar, Lewis could not ignore Arab anti-Semitism and the growth of Israel-hatred. Even when Middle East Studies became politicized, Bernard Lewis stood out as a beacon of integrity and a supporter of Israel.

George Shultz (47 of 70)

When Natan Sharansky gained his freedom, U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz was the first person to phone him. Shultz had campaigned directly with Soviet leaders for Sharansky’s release and, with the support of President Reagan, had made freedom for Soviet Jews a key issue in his talks with Russian leaders.

Yet typical of the humble Shultz, he speaks of his debt to those he helped free, remarking that he has “a great sense of gratitude to the Soviet Jews because they showed us what courage is all about.” Years later, he told Sharansky: “You played a crucial role in bringing down the Iron Curtain and giving freedom to the [Russian] people. I can assure you that your name will remain with us forever as a liberator of millions of Soviet Jews.”

This is true, of course, of Shultz himself. A Marine artillery officer in World War II, he is one of only two men to have served in four different U.S. cabinet positions.

But he made his mark as a devoted advocate for freedom. Shultz consistently supported Israel, recognizing its importance as an American ally. That commitment was shown during his six-and-a-half years as Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of State. In 1982, during the Lebanese Civil War, his shuttle diplomacy helped bring Israel’s forces safely away from Beirut, and in 1988, he labored to bring an end to the first intifada.

Shultz also helped Israeli leaders deal with hyperinflation during the 1980s, noting that Israel wouldn’t be safe unless it got its budget in order. He put together an American-Israeli Joint Economic Development Group aimed at stabilizing the Israeli economy, and helped shepherd through emergency economic assistance to Israel. Shultz also was instrumental in putting together America’s first free-trade agreement — with Israel of all countries — in 1986.

Though rarely mentioned today, Shultz’s efforts were vital in stabilizing the Israeli economy and helped lay the groundwork for its astonishing success in the decades that followed.

Most recently, Shultz, 97, has spoken out about the inherent difficulty of assuring Iranian compliance with any nuclear agreement, and of the risks posed by Iran as a determined enemy of freedom and the West.

Throughout his distinguished career in public service, Shultz has never wavered in his determination to support freedom and in his friendship towards Israel.

Walter Lowdermilk (1888–1974) (48 of 70)

How would the State of Israel survive, much less thrive, in a land where water was so scarce?

The genius who solved this riddle was Walter Lowdermilk. Raised in arid Arizona, Lowdermilk majored in chemistry at one college, then engineering at another, followed by a Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford to study German forests. Then he worked to prevent the cycle of floods and famines faced by Chinese peasants.

These experiences prepared Lowdermilk for his life’s occupation: blending soil conservation and water management. Those skills were further honed during his tenure with the U.S. Forest and Wildlife Service’s Soil Conservation Service.

An extended stay in British Mandate Palestine inspired his 1944 bestseller Palestine, Land of Promise. It presented a detailed plan for water use and land reclamation. In his book, Lowdermilk claims that the Jewish people “demonstrated the finest reclamation of old lands that I have seen in three continents … by the application of science, industry and devotion … [they have acted against] great odds and with sacrificial devotion to the ideal of redeeming the Promised Land.”

The book sparked interest in and admiration for the pioneering settlers, and, along with Lowdermilk’s meetings with American leaders, convinced Western intelligentsia that a great and populous country could be built by Jews amid the deserts of Palestine. Integral to this, he explained, was use of the Jordan River to provide drinking water and electricity, and the Litani River to irrigate the Negev.

Lowdermilk outlined a visionary proposal to build a hydroelectric canal extending from the Mediterranean to the Dead Sea. In all, he set forth what has been called “the Lowdermilk Plan”: an outline for the creation of the nation’s water system.

He also criticized the White Paper of 1939, warning that limiting Jewish immigration to Palestine would lead to massacres of Jews by Arabs.

Lowdermilk returned to Israel in 1951. Now called “the father of the Israel water plan,” he stayed through 1957, guiding the setup of Israel’s Soil Conservation Service and helping to establish the Technion University’s School of Agriculture and Engineering, which was later named after him.

His writing provided impetus for the construction of the National Water Carrier. In appreciation of his many contributions to the Jewish state, Israel Minister of Development Mordecai Bentov put it best: “We don’t need powdered milk. We need Lowdermilk.”