Israel salutes America: 70 who counted in 70

On the occasion of the Jewish state’s 70th anniversary, the Israeli embassy in Washington, in partnership with the JNS news service, celebrates 70 of the greatest American contributors to the U.S.-Israel relationship

Many of the people and organizations chosen for this acknowledgement will be readily recognized by readers of The Jewish Star, others less so, but their powerful stories build a collective history that reflects the broad base of American love and support for the Jewish State.

This week, The Jewish Star publishes the first in a series that will cover all of the “70 who counted.”

Link here to all 9 installments:

Isaiah ‘Si’ Kenen (1905-1988) and AIPA 1 of 70

The small town of St. Stephen in maritime Canada is an unlikely birthplace for a giant of 20th-century pro-Israel leadership. Yet for Si Kenen, born there in 1905, Zionism was integral to his family heritage, and his life was defined by dedication to the Jewish state.

Kenen’s father had been an Orthodox Zionist, who had known Theodore Herzl and other Zionist leaders in Europe. Having immigrated to Canada from Kiev in the Russian Empire, the Kenens made their way to Toronto, where Si attended college and later found work as a journalist, later moving to Cleveland where, in 1941, he became head of a Cleveland Zionist chapter.

Kenen threw himself into Zionist work, becoming an information director of the Jewish Agency and then a member of Israel’s first UN delegation in 1949. In 1951, he set up the American Zionist Committee—soon to become AIPAC—convinced that a strong Israel would make America stronger. Kenen understood that, although now independent, the State of Israel faced enemies and many domestic challenges; it would require an organized force of American citizens to strengthen Israel and the US-Israel relationship.

It was a brilliant assessment of the way Washington worked and a bold move, made at a time when some American Jews still preferred to keep quiet about their love of Israel.

Frank Sinatra (1915-1998) 2 of 70

One of the greatest singers of the 20th century, Frank Sinatra always had universal appeal. Although there is no Sinatra number called “Moonlight in Tel Aviv,” for his entire life, “Old Blue Eyes” was an ardent philo-Semite, an unstinting supporter of Zionism and the Jewish state. Indeed, as Sinatra’s long-time assistant wrote in a memoir, Israel was Mr. S’s “favorite country.”

Growing up in immigrant-heavy Hoboken, NJ, Sinatra developed a keen sense of the discrimination faced by Italian and Jewish newcomers to America. As Shalom Goldman wrote, Sinatra’s early life was filled with Jews. One nanny, a certain Mrs. Golden, spoke only Yiddish, causing him to later joke that he “knew more Yiddish than Italian.”

By 1947, Sinatra had already long been one of the most famous singers in America. In contentious pre-state days, he lent his prestige to the cause, appearing at a pro-yishuv benefit concert at the Hollywood Bowl. Nor was Sinatra above getting his hands dirty. In 1948, he helped future Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek illicitly ship weapons from New York to Palestine. “I wanted to help [the Zionists],” he later recalled; “I was afraid they might fall down.”

Sinatra first visited Israel in 1962, on his first international tour, and he came to love the reality of the state as much as he loved the image he had developed of it. He marked Israel’s 40th birthday alongside David Ben-Gurion and Moshe Dayan, and gave a concert to paratroopers-in-training at Tel Nof.

Sinatra returned frequently to Israel in later years and gave generously of his time and money to Israeli causes. He financed a Catholic church and youth center in Nazareth, and raised one million dollars to open a student center in his name at the Hebrew University. All of these institutions remain active to this day.

What explains Sinatra’s love of Israel? Surely the New Jersey melting pot, and his Christian faith, played a part. But he also saw in Israel a quality that he greatly admired: moral and spiritual toughness—dusting yourself off after it seems as if you’ve gone down for the count—living to fight another day and, perhaps most of all, doing it your way.

Henrietta Szold (1860-1945) and Hadassah 3 of 70

An early American Zionist leader who was also learned in traditional Jewish texts and scholarship, Henrietta Szold was notably ahead of her time. Born to a Jewish family in Baltimore in 1860, Henrietta’s father was a rabbi who ensured that she received a Jewish education. As a result, she became involved in teaching, as well as in editing and publishing Jewish texts, an unheard form of scholarship for women at that time.

An example of her work, familiar to many English speakers who have studied Talmud, is the Marcus Jastrow’s Dictionary of the Talmud, which she edited. Szold also served as the sole female editor for the Jewish Publication Society, translating, editing and preparing works for publication. Szold continued her formal Jewish education at Solomon Schecter’s Jewish Theological Seminary.

A committed Zionist since its early days, Szold visited Palestine for the first time in 1909 and immediately devoted herself to work for the betterment of its population. She founded an organization called Hadassah, which focused on improving health care in Palestine. Under Szold’s leadership, Hadassah created hospitals, nursing programs and facilities as well as many important health and education services.

Hadassah, also known as the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, continues to operate as one of the largest international Jewish organizations with well over 300,000 members in the United States. One notable leader was Miriam Freud-Rosenthal, who carried on Szold’s legacy in Hadassah until her death in 1999. Over the decades, the women of Hadassah have supported a number of programs and wide range causes, branching out from the initial immediate need of improving medical care in the early days of the Jewish community in Palestine.

Szold ensured that the medical programs founded and funded by Hadassah would be available for all residents of Palestine and subsequently the State of Israel, regardless of an individual’s race, ethnicity, or religion. Thus it was quite appropriate that Hadassah was involved in the opposition in 1975 to the UN General Assembly Zionism is racism resolution.

Szold came to Palestine to live permanently in 1933. A year later, she inaugurated the new Hadassah-funded hospital on Mount Scopus. This is the same Hadassah Hospital which operates today as one of the central and foremost medical facilities in Israel.

Louis Brandeis (1856-1941) 4 of 70

Living the American dream and following a path that would ultimately land him on the Supreme Court, Louis Brandeis had little time for Zionism in his early life and even held views that were antithetical to it.

But that changed in 1914, when Jacob de Haas, a former secretary to Theodore Herzl, came for what turned out to be an important visit. De Hass asked Brandeis if he was related to a prominent Kentucky Jew by the name of Lewis Dembitz, who was ardently and publicly both a Jew and a Zionist. This was indeed Brandeis’s uncle. Reflecting on this meeting and the noble conduct of his uncle, Brandeis began to recognize that there need not be a contradiction between Zionism and Americanism, and that Zionism and Americanism in fact ennobled one another.

From then on, Brandeis passionately devoted his intelligence and influence to Zionism. Over the course of World War I, he became an acknowledged leader of the American Zionist movement. Touring America and drumming up support for Zionism, he raised large sums of money for the yishuv.

Perhaps Brandeis’s greatest achievement came in 1917, as the British Government was weighing whether to issue the Balfour Declaration. He helped persuade President Woodrow Wilson that America should be entirely behind the declaration—and, by extension, favorable to a Jewish homeland.

Nahum Goldman, who would become president of the World Zionist Organization, stressed the centrality of the Brandeis intervention. Without Brandeis, he wrote, “the Balfour Declaration would probably never have been issued.”

In the first part of the 20th century, many sectors of American Judaism had been skeptical of Zionism. Precisely because Brandeis had once held this view himself, he was able to break it down through a powerful conviction that America and Zionism shared a commitment to justice, righteousness and liberty.

The Galilee kibbutz of Ein Ha’Shofet (“Spring of the Judge”) was established in honor of Louis Brandeis and stands as a permanent testament to his devotion to the State of Israel.

Elmo ‘Bud’ Zumwalt Jr. (1920-2000) 5 of 70

Elmo Russell “Bud” Zumwalt Jr. was a decorated war veteran who rose through the ranks of the U.S. Navy to serve as its youngest Chief of Naval Operations, commanding U.S. naval forces in the Vietnam War and modernizing many aspects of navy policy and strategy.

Admiral Zumwalt believed strongly that the United States should aid Israel in its conflicts with the surrounding Arab countries. During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Zumwalt played a critical role in airlifting supplies to Israel that were a crucial factor in Israel’s victory.

In an oral history recorded in 1991, Zumwalt recounted that he approached Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger and conveyed to him that Israel was losing the war and would run out of ammunition in one or two days, and that it was therefore essential that America transfer supplies and equipment to Israel immediately. Lacking authority from President Nixon, Schlesinger said there was nothing he could do. Refusing to take no for an answer, Zumwalt turned to Senator Scoop Jackson to mobilize pressure on the Nixon administration. Zumwalt unhesitatingly risked his career by briefing Jackson every day, helping him to outmaneuver the opponents of resupply. His persistence paid off at the last minute when Nixon authorized a massive airlift using Air Force C-5 cargo planes.

Zumwalt was then directly involved with the logistics of actually getting the supplies to Israel, which proved to be no easy matter. He had to “lean pretty hard” on various nations who controlled essential airspace on the route necessary for transit and refueling. En route to Israel, the planes landed in the Portuguese Azores, refueled over Spain, and were supported by a fleet of ships based in Greek waters. All three nations were at that time controlled by indifferent or even hostile regimes. This massive airlift, known as Operation Nickel Grass, resulted in over 22,000 tons of weapons and supplies, including one hundred fighter jets being sent to Israel. In many instances, the supplies reached the front lines within a few hours of landing, directly contributing to Israel’s victory.

The operation could not have gone forward without the determined efforts of Admiral Zumwalt who, like Scoop Jackson, should be remembered for decisive action that helped save Israel in one of its most vulnerable moments.

James Grover McDonald (1884-1964) 6 of 70

Few individuals have contributed as much to the cause of the Jews and Israel as James Grover McDonald. An unwilling witness to the pivotal events that led to the Holocaust, McDonald was a fervent and essential advocate for the creation of the Jewish state.

A native of Indiana, McDonald came from a family of hoteliers. Educated at Indiana University and then Harvard, McDonald spoke fluent German, given his mother was an immigrant from there. That skill served him well when he met with Nazi officials as U.S. representative to the League of Nations’ High Commission on Refugees.

Appointed in 1933, McDonald strove tirelessly to arrange for the transfer of Jews out of Germany. This required him to work closely with Chaim Weizmann. Conversations with Nazi officials persuaded him of the enormity of the situation and of the vital importance of creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Frustrated by the difficulty of raising money or gaining support from the High Commission, McDonald resigned in 1938 and went to work as an editorial writer at the New York Times, where he was an unrelenting voice for Zionism. Eventually, he returned to official service, co-authoring a report in 1945 that called for the immediate admission of 100,000 Jewish displaced persons to British Mandated Palestine, an idea that President Truman supported but the ruling British Labour Party opposed. Meeting the following year with British leaders, he implored them to adopt a more pro-Jewish attitude.

Two years later, President Truman appointed McDonald as U.S. Special Representative. Fighting with his Arabist State Department aides, he consistently argued for U.S. support and recognition for Israel and for admission of Jewish refugees from around the world. This battle continued when McDonald became the first U.S. ambassador to Israel.

Even after retirement, McDonald continued to advocate for American support for Israel. To that end, McDonald led a campaign for the purchase of $500 million in Israel bonds.

Explaining himself, he commented: “I am confident that it [Israel] will be a civilizing, modernizing and democratizing influence in the whole region.”

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) 7 of 70

Leonard Bernstein was an American conductor, composer and pianist who became one of the most renowned figures in American musical history and world-famous as the conductor of the New York Philharmonic, as well as the composer for such Broadway musicals as West Side Story.

Born to Jewish immigrants in 1918, Bernstein immersed himself in music from an early age, eventually studying music at Harvard University. Some of Bernstein’s musical compositions have clear associations and references to Jewish themes. One of the most obvious is his first symphony, which he conducted at its premiere in 1944. Titled Jeremiah, it follows the life of the biblical prophet. In addition to a soloist singing lines in Hebrew from the book of Lamentations, the second movement’s music is instantly recognizable to Jewish ears as based on the cantillation of the haftarah.

From early on, Bernstein felt a strong connection to and passion for the people and land of Israel. Deeply affected by his first visit to Israel in 1947, he wrote to his mentor Serge Koussevitzky, “I am simply overcome with this land and its people.” In 1948, Bernstein led the Israel Philharmonic on a whirlwind tour of 40 concerts, conducting under the threat of artillery fire from nearby enemy forces. At one concert, after being called offstage and informed about a possible incoming air raid, Bernstein immediately sat back down at the piano and continued to play.

His most important moment in Israel came on Nov. 20, 1948. The previous day, the United Nations ordered Israel to withdraw its forces from Beersheva, which they had captured a few weeks earlier. Israel refused, and the Israel Defense Forces remained entrenched in this strategic southern city.

The next day, Bernstein and the Philharmonic arrived and put on a concert for the thousands of soldiers holding fort. Held on a makeshift stage at the site of an archaeological dig, the concert was a moving experience for many of the soldiers and for Bernstein as well.

Bernstein maintained his close relationship with Israel throughout his life. Visiting almost every year, he helped develop the Israel Philharmonic into one of the world’s premiere orchestras.

Eddie Jacobson (1891-1965) 8 of 70

Eddie Jacobson’s life-long friend Harry Truman was hardly known for fulsome praise. So when Truman described him “as fine a man as ever walked,” it was a tribute not to be taken lightly. Humble and unaffected, Jacobson did not seek out a high place in the world. However, when given the chance to act nobly, he did.

The son of a milkman, Jacobson grew up in Leavenworth, Kan., and Kansas City, Mo. He first met Truman at the age of 14, but the two didn’t become friends until 12 years later, when they underwent basic training together at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Their success in running an army canteen inspired them to open the Truman-Jacobson Haberdashery in Kansas City after the war.

In the post-war slump, the store went bankrupt, leaving both men with sizable debts. Determined to repay their creditors, they spent decades doing so. During this time, Truman rose as a political leader, and Jacobson took on a career as a traveling salesman. Despite their failed venture, they remained the closest of friends throughout their lives.

Jacobson had free access to Truman even after he became president. During his visits, the two would discuss the situation in Europe and what could be done to rescue European Jewry. On many occasions, Jacobson brought along Zionist leaders like Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld and attorney A.J. Granoff to meet Truman, underwriting their trips to Washington.

By March 1948, Truman was weary of the solicitations from Jewish leaders regarding Israel. Unsure of how to respond to requests for recognition of the Jewish state, he even refused to meet with Chaim Weizmann regarding the issue.

That was when the future UJA leader Dewey Stone and then B’nai B’rith president Frank Goldman called Jacobson from a Massachusetts payphone. Stone had spent the day with a frustrated Weizmann. Goldman mentioned to Stone that he had just given a B’nai B’rith award in Kansas City to Jacobson for his various good deeds. Together, they beseeched Jacobson to meet Weizmann. The future president of Israel in turn asked Jacobson to intercede with Truman.

A mere six days later, Jacobson appeared unannounced at the White House. He explained to the president that Weizmann was “the greatest Jew alive” and begged him to speak with him once more. Truman agreed.

At their meeting, Truman promised to work for the establishment of the Jewish state. Not quite four weeks later, on May 14, 1948, America became the first country to recognize Israel.

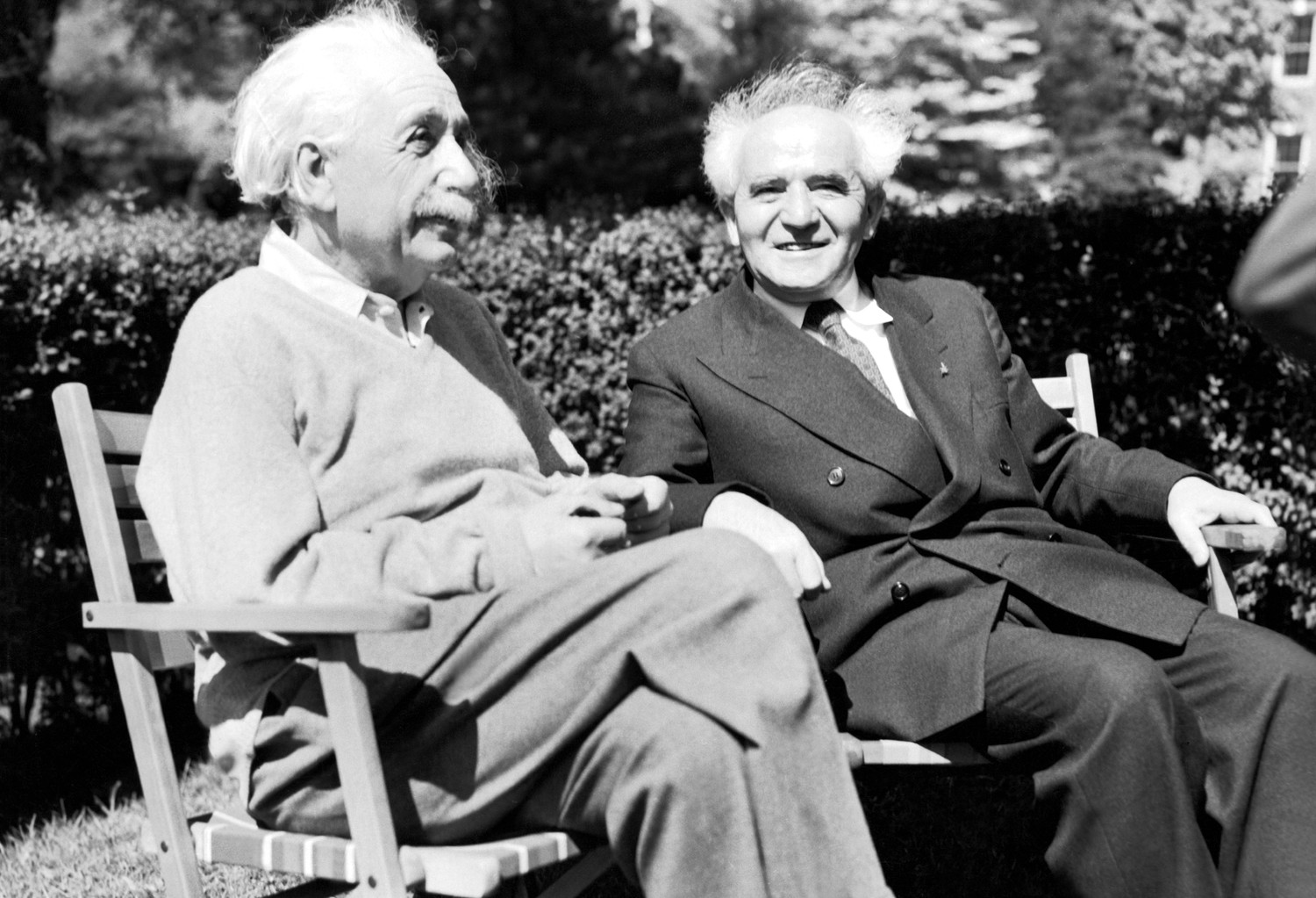

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) 9 of 70

The one generally known story about Albert Einstein and Israel is true. The 20th century’s greatest scientific genius refused David Ben-Gurion’s offer to become its second president.

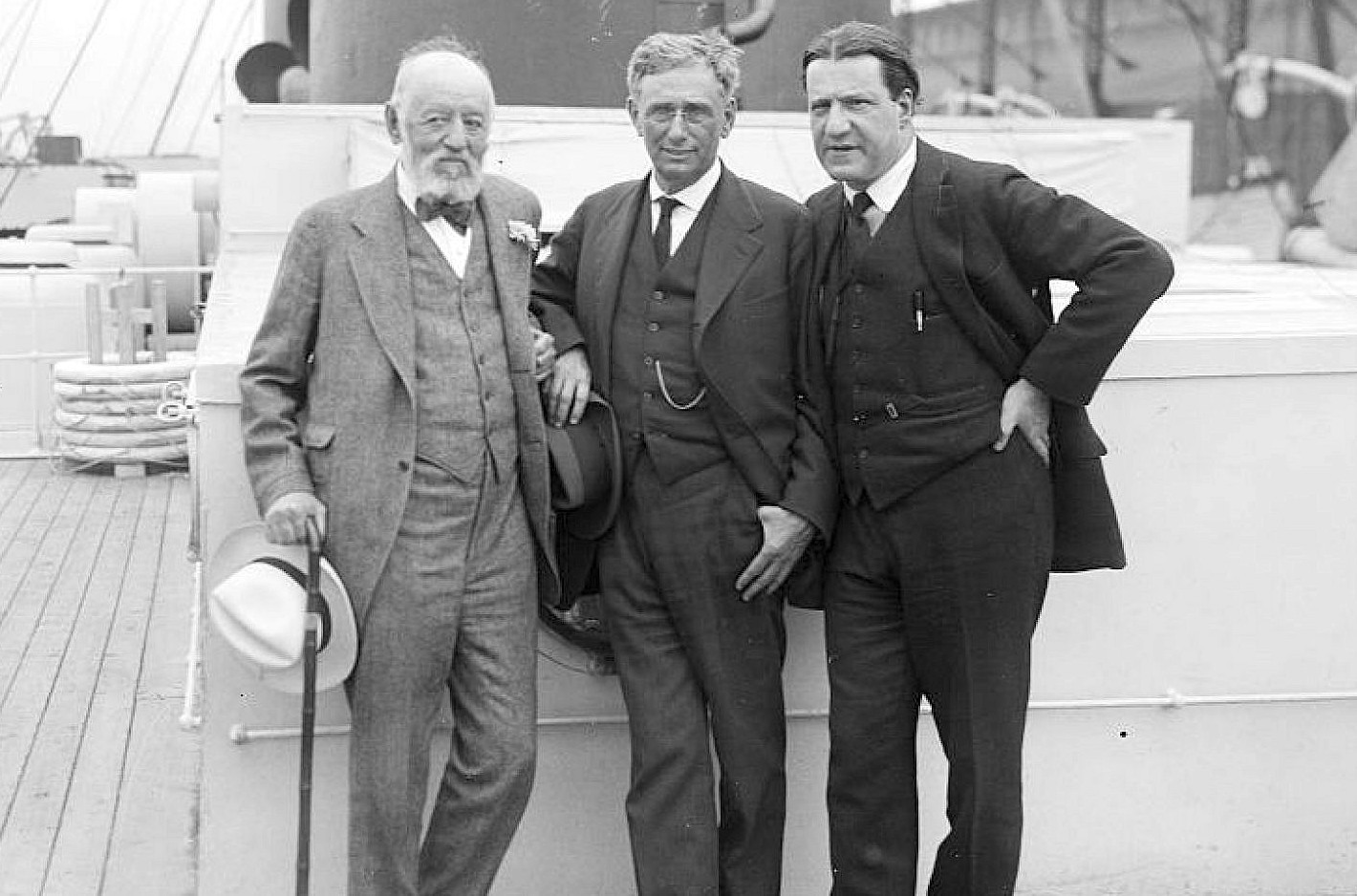

But this fact yields a false sense of Einstein’s relationship with Zionism. Einstein was a Zionist from 1919 onwards, when he was converted to the cause by Chaim Weizmann’s lieutenant, Kurt Blumenfeld. Thus, in 1921, Einstein accompanied Weizmann on a fundraising tour of the United States for the planned Hebrew University. Attracting front-page headlines and enthusiastic crowds, it raised $700,000—a remarkable sum in those days.

Two years later, in February 1923, Einstein visited British Mandate Palestine. During this trip, he gave the first scientific lecture at Hebrew University and joined Weizmann on its board of governors. Einstein continued to raise money for the university into the 1950s. On that visit, he also planted a tree in front of the Technion, an institution he would later support, including serving as chairman of the Technion Society.

In the 1930s, Einstein took on an honorary post as chairman of the United Jewish Appeal. This involved more than lending his name. Einstein gave radio addresses about the dangers Jews faced in Europe, and he denounced the limitations against Jewish emigration into Palestine.

Einstein’s decision to turn down Israel’s presidency was certainly not motivated by disregard or indifference, but rather by respect. As he put it, “I am deeply moved by the offer from our State of Israel, and at once saddened and ashamed that I cannot accept it. … I lack both the natural aptitude and the experience to deal properly with people and to exercise official functions. … I am the more distressed over these circumstances because my relationship to the Jewish people has become my strongest human bond, ever since I became fully aware of our precarious situation among the nations of the world.”

In the last days of his life, Einstein was working doggedly on a speech in support of Israel. Although he died before he was scheduled to deliver it, the address survives. In it, he said Israel’s creation was “an event which actively engages the conscience of this generation. It is, therefore, a bitter paradox to find that a state which was destined to be a shelter for a martyred people is itself threatened by grave dangers to its own security. The universal conscience cannot be indifferent to such peril.”

Einstein bequeathed his personal archives and all literary rights to his works to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Howard (1909-2014) and Lottie (1916-2015) Marcus 10 of 70

Dr. Howard and Lottie Marcus, originally of Great Neck, later of San Diego, were blessed with very long lives. Howard died at the age of 104 in 2014, and Lottie died in 2015 at the age of 99. Their deaths did not preclude them from causing quite a stir a few months later.

In June 2016, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev announced shocking news. The Marcus estate had gifted a sum of $400 million to the university. This incredible sum more than doubled the university’s endowment overnight and was the largest charitable gift ever bestowed upon an Israeli institution, academic or otherwise.

Both Howard and Lottie lost almost their entire family in the horrors of the Shoah and were intent that their gift go towards helping educate young Jews.

They met after the war in New York, Lottie working as a secretary on Wall Street and Howard as a dentist. The Marcuses made their fortune through none other than Warren Buffet. Befriending him in the early 1960s, the Marcuses joined his investment partnership, amassing an enormous fortune in the process. Despite their financial success, they lived modestly in a middle-class neighborhood in Great Neck and retired to a one-bedroom apartment in San Diego. Described as warm and friendly, they barely touched their fortune.

The Marcuses first became involved with Ben-Gurion University in the late 1990s. They were particularly enthralled by the university’s work in desalination and advanced irrigation of desert environments. They believed that solving the region’s problem of water scarcity would be an important step toward a lasting peace. A large portion of Howard and Lottie’s gift to the university is dedicated to the Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research at the university, which studies sustainable water usage and desalination, among other important research areas.

Amazingly, Howard and Lottie’s donation to Ben-Gurion University represented almost the entirety of their estate. Consistent with the manner in which they lived their lives, they viewed what they had earned as something to modestly hold onto, until the time was right to give back to the Jewish homeland and its people.

Pick up next week’s edition of The Jewish Star for more of the 70 who mattered.