How I learned to dance

Posted

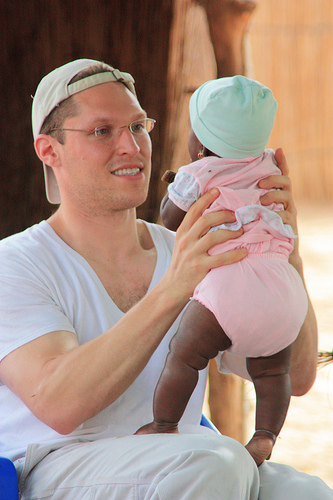

Shared humanity in an African village

By Gilah Kletenik

Issue of September 25, 2009/ 7 Tishrei 5770

No one would accuse me of being a dancer. In fact, I’ve been diagnosed with that special syndrome called “rhythm deficiency.” Which is why, in retrospect, it seems decidedly ironic that one of my most uplifting moments transpired on the dance floor. Of course, this was no ordinary dance floor.

It was a sandy desert ground in the village of Darou Mouride, located in rural Senegal, Africa, and this kind of dance, not to mention the music, was certainly nothing I’d ever experienced before — after all, this was our first day in Senegal. To welcome us, the villagers greeted us with a dance. But, it isn’t the novelty that made this experience so memorable. Rather, it’s the authenticity of the dance that has been tickling my heart ever since.

There were a host of reasons why I applied to American Jewish World Service’s ten-day Rabbinical Students’ Delegation to Senegal (a disclaimer, I am not a rabbinical student, only a graduate student studying Talmud).

I wanted to build latrines for two villages in the Global South; I wanted to engage with future Jewish leaders from across the denominational spectrum; and I wanted to go to Africa — but dance? I had no interest. I hoped to really give of myself, to finally translate my values of Tikkun Olam into sustainable, lasting change. But really, the latrines we were sent to build and my part in lugging bricks and stirring concrete was fungible — I did not have to be there. I’ll be honest; none of us had to be there. Shockingly, flying 25 rabbinical students across the world for a week and a half is not the most effective way of erecting latrines. This became clear immediately.

In one of his famous parables, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov taught that to help someone out of misery one must not reach down into the trenches from above, but one must plunge into the pit together with the person in need. I had always wondered why. The task might be done just as effectively, if not more so, from outside the pit than from within. What is the benefit of descending into the depths?

Rabbi Nachman’s demand that we join the needy in their neediness closes the distance between both parties and draws them together. To do otherwise presupposes a hierarchy, and the strictly prescribed roles of giver and recipient.

When we began to dance with the Senegalese villagers the foreignness immediately evaporated and the blatant boundaries were broken. There no longer existed the hierarchy of the donor and the recipient, of the white oppressor and black victim, of the Jew and the Muslim. Instead, we were all people, briefly escaping the vicissitudes of our reality, united in our humanity.

In the middle of the dancing, a woman got up from nursing her child to tie a rinted cloth around my waist, skirt-like. She proceeded to show me how to dance by incorporating the cloth into my moves. Dancing there together, we looked into each other’s eyes and I had a glimmer of understanding; I felt the sparkle of Tzelem Elokim, the G-dliness, in both of us. Finally, Rabbi Nachman’s teaching became clear.

Soon, the dancing died down, reality set in and it was time to get to work. I began to notice my surroundings. There was arid desert in all directions; the village’s fields yielded just a quarter of what they once did. The odor of goat and donkey droppings was everywhere; most villagers walked barefoot through this mess because they did not own shoes. I felt guilty reaching for my bottle of filtered water as I drew water for the villagers from the well.

As I sat in my new friend Anta’s home I wondered what it felt like to live in a thatched hut without electricity or running water. I cheerfully tried to acquire the skill of millet grinding and sifting, though it was painful to know that whatever we ground would not be enough to feed Anta’s malnourished extended family. When I spoke to the villagers in my broken version of their language, Woolof, I delighted in bringing a smile to their faces, but witnessed their missing teeth and the sorry state of their infected gums. The children had flies in their eyes and distended bellies. There was brokenness everywhere.

The word in Woolof used to respond to a greeting is, “mangifee,” which literally means, “I am here.” The more times I said it, the more times I took it in. When a half dozen little boys would run after me screaming “Gilah, Gilah, Gilah;” when Anta would patiently teach me the same song over and over again and when Cheerno, our driver, would walk me through the village teaching me the Woolof words for everything we encountered, I felt no brokenness and saw no desperation in their eyes. I was not the privileged American there to help them and they were not the distressed Africans struggling to survive. We were all human beings, with our own hopes and dreams, pains and fears, joys and loves; we were all created by G-d, cousins descended from Adam, made in His image.

It is this shared humanity of ours that demands a response. This also explains why it made perfect sense for my 25 colleagues and me to travel all the way to Senegal. Only once we encounter the humanity in the other are we compelled to turn towards the other, even if he or she is geographically or culturally distant.

Even after my African dance boot camp, I still am not a dancer. But, on the sandy ground of Darou Mouride, thousands of miles from home, I danced for the first time.

Gilah Kletenik is a Fellow in The Graduate Program for Advanced Talmudic Study at Yeshiva University and a student in The Bernard Revel Graduate School. She is co-Director of the Eilu ve-Eilu Fellowship at Drisha. To make a micro-loan to villagers in Senegal you can go to kiva.org or donate through the website of the American Jewish World Campaign at http://action.ajws.org/goto/gilah.kletenik.

Report an inappropriate comment

Comments

56.0°,

Overcast

56.0°,

Overcast