How anti-Semitism replaced historic black-Jewish alliance

African-Americans committed many of the recent anti-Semitic attacks in New York and New Jersey. What makes that especially sad is that blacks and Jews were allies during the Civil Rights fight in the 1960s.

At the January 1963 National Conference on Race and Religion in Chicago, opened his address with these words:

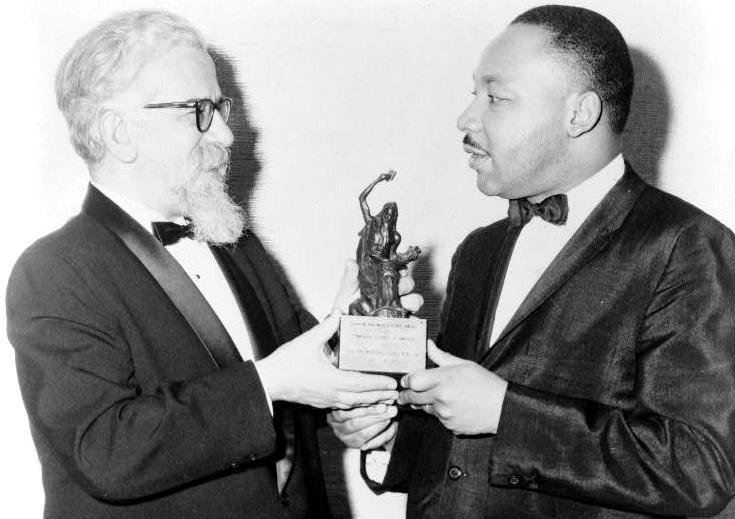

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. described Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel as “one of the great men of our age, a truly great prophet” who “has been with us in many struggles. I remember marching from Selma to Montgomery, how he stood at my side. … I remember very well when we were in Chicago for the Conference on Religion and Race. … To a great extent, his speech [there[ inspired clergymen of all faiths to do something they had not done before.”

To Rabbi Heschel, the civil rights movement was an essential responsibility of all religious leaders. In June of 1963, he sent a telegram to President Kennedy that said: “Please demand of religious leaders personal involvement, not just solemn declaration. We forfeit the right to worship G-d as long as we continue to humiliate Negroes. Church and Synagogue have failed. They must repent. … I propose that you Mr. President declare state of moral emergency. A Marshall Plan for aid to Negroes is becoming a necessity. The hour calls for moral grandeur and spiritual audacity.”

When King made his famous march to Selma, Alabama, he walked hand in hand with many Jews, including Rabbi Heschel. When he made stood at the Lincoln Memorial and said, “I Have A Dream,” Rabbi Heschel and a contingent of Jews were there with him.

In 1965, King said: “How could there be anti-Semitism among Negroes when our Jewish friends have demonstrated their commitment to the principle of tolerance and brotherhood not only in the form of sizable contributions, but in many other tangible ways, and often at great personal sacrifice. Can we ever express our appreciation to the rabbis who chose to give moral witness with us in St. Augustine during our recent protest against segregation in that unhappy city?

“Need I remind anyone of the awful beating suffered by Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld of Cleveland when he joined the civil rights workers there in Hattiesburg, Mississippi? And who can ever forget the sacrifice of two Jewish lives, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, in the swamps of Mississippi? It would be impossible to record the contribution that the Jewish people have made toward the Negro’s struggle for freedom — it has been so great.”

Rev. King was due to come to the rabbi’s house to attend a 1968 Passover seder. But sadly, a week before the holiday, on April 4, 1968, James Earl Ray killed King with a single shot fired from his Remington rifle and robbed the country of the great leader.

People like Jesse Jackson inherited the leadership of the Civil Rights movement. The new leadership saw the Jews as the African-Americans’ competition for achieving middle-class status. Black leaders such as Jackson, Andrew Young and Louis Farrakhan made public anti-Semitic comments. The hatred didn’t infest all black Americans, but too many forgot King and hopped on the hating bandwagon.

In his book Race Matters, Cornel West contends there were no good times when “blacks and Jews were free of tension and friction.” West says that the 1960s period of black-Jewish cooperation is often downplayed by blacks and romanticized by Jews, “It is downplayed by blacks because they focus on the astonishingly rapid entry of most Jews into the middle and upper-middle classes during this brief period — an entry that has spawned … resentment from a quickly growing black, impoverished class.”

The alliance forged by the Reverend King and Rabbi Heschel began to split.

An incident that widened the split occurred in New York City in 1968. A new community-controlled school board in the mostly black Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn fired 18 white teachers and administrators — many Jewish — because of their skin color. The school board’s action led to a series of citywide teacher strikes led by the United Federation Of Teachers leader Albert Shanker. During the work-stoppage African-American anti-Semitism was directed at Shanker and other Jewish members of the UFT. Anti-Semitic catcalls were shouted by protesters and appeared in newspapers put out by the Afro-American Teachers Association.

Leaders of the South African anti-Apartheid movement traveled throughout the United States spreading Jew-hatred. In 1984, Desmond Tutu publicly complained about American Jews. Accusing them of exhibiting “an arrogance of power because Jews are a powerful lobby in this land and all kinds of people woo their support.” Speaking in a Connecticut church, Tutu said that “the Jews thought they had a monopoly on G-d; Jesus was angry that they could shut out other human beings.”

The Affirmative Action movement further divided the two allies. Jews fought against it because they believed everything should be based only on merit.

In 1979. Andrew Young, then President Jimmy Carter’s ambassador to the United Nations, violated administration policy and met with a representative of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Almost immediately, Young was fired. By most accounts, he was asked to resign because he had deceived the State Department — but black leaders saw a Jewish conspiracy. Young’s dismissal, said Jesse Jackson, was a “capitulation” to Jews.

Al Sharpton was a low-level civil rights leader who was looking to become “big time” by using Jews as his scapegoat. During the Twana Brawley hoax, he said that Brawley telling her story to New York State Attorney General Robert Abrams, who was Jewish, would be “like asking someone who watched someone killed in the gas chamber sit down with Mr. Hitler.”

On July 20, 1991, Leonard Jeffries of City College, who had a history of making anti-Semitic slurs, presented a two-hour long speech in which he claimed that “rich Jews” financed the slave trade and control the film industry with Italian mafia and use that control to paint a brutal stereotype of blacks. Jeffries called Assistant Secretary of Education Diane Ravitch a “sophisticated Texas Jew,” “a debonair racist,” and “Miss Daisy” (as in Driving Miss Daisy).

Jeffries’ speech received enormous negative press, especially from Jewish leaders who wanted him fired for the bigotry. He was removed as chairman of the black studies program but allowed to stay on as a professor — and regained the position of chairman after he sued the school.

With each new criticism directed at Jeffries, leaders in the New York African-American community rushed to his defense. The city’s two black newspapers, as well as black radio station WLIB, joined activists such as Sharpton, Colin Moore, C. Vernon Mason, Sonny Carson, and Lenora Fulani to showcase their approval of Jeffries’s “scholarship.” At the same time, they denounced the Jews who criticized Jeffries as anti-Semitism as race-baiters.

On Aug. 18, 1991, speaking about the growing Jeffries controversy, Sharpton made his famous comment: “If the Jews want to get it on, tell them to pin their yarmulkes back and come over to my house.”

The day after that comment, a car in the motorcade of the Lububcher Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson accidentally jumped the curb in Crown Heights and killed a young black child, Gavin Cato. More than 250 neighborhood residents, mostly black teenagers, went on a rampage that first night, many shouting “Jews! Jews! Jews!”

Sharpton wasn’t there on the first night when a Jewish Yeshiva student from Australia named Yankel Rosenbaum was killed. But seeing the possibility of becoming a national leader, Sharpton joined in on day two and attacked the Jews.

On the second day of the Crown Heights riot, according to the sworn testimony of Crown Heights resident Efraim Lipkind, Sharpton started agitating the crowd. “Then we had a famous man, Al Sharpton, who came down, and he said Tuesday night, kill the Jews, two times. I heard him, and he started to lead a charge across the street to Utica [avenue].”

On the third day of the pogrom, Sharpton and Sonny Carson led a march of protesters chanting, “No Justice, No Peace!” “Death to the Jews!” and “Whose streets? Our streets!” The mob displayed anti-Semitic signs and burned an Israeli flag.

On the back of his scapegoating of Jews, Sharpton become a national figure. He left behind an widening divide between Jews and blacks.

According to the ADL, between 2007 and 2016, African American anti-Semitism was almost twice that of the general community. While these numbers are frightening, it is essential to note that the vast majority of African Americans are NOT anti-Semitic.

At the end of 2019, there was a rash of anti-Semitic incidents in the New York area perpetrated by African Americans, including the machete attack in Monsey and the shooting attack at a kosher grocery in Jersey City. After the shooting, members of the African American community in Jersey City spewed anti-Semitic comments, including one by a member of the city’s school board.

How do we reverse the spiral of hatred? How do the Jewish and African American communities go back to the days of Rabbi Heschel and Dr. King?

Leadership!

I am not an expert on African American leadership, but I suspect the problem with their leaders is similar to the issue with Jewish community leaders. Most leaders of major Jewish community organization leaders don’t prioritize anti-Semitism or mending fences with other communities. Judging by their actions, their top priority is pushing the progressive goals of the Democratic Party. That’s why so many Jewish leaders kiss up to the anti-Semitic Al Sharpton, supported Barack Obama despite his anti-Semitism, allowed the House Democrats to get away with their BDS support, and so on.

Jewish organizations contend that President Donald Trump, the most pro-Jewish president in recent decades, is an anti-Semite, while his only real offense is that he is a conservative Republican.

I have never met a conservative African American who hated Jews and didn’t support Israel. I suspect that black leadership, like Jewish leaders, put progressive politics before the needs of their people

If Jews demand that their leadership address the needs of their people as a priority over liberal politics and if African Americans demand the same from their leadership, it would be one giant step toward bringing back the alliance forged by two great leaders during the 1960s.

39.0°,

Fair

39.0°,

Fair