Films romanticize and sanitize US Communists

If you like movies, you shouldn’t miss the chance to see Christopher Nolan’s brilliant new film “Oppenheimer.” Though oddly linked with the even more popular “Barbie” as a record-breaking summer blockbuster duo, the biopic about Robert Oppenheimer — the nuclear physicist who led the effort to create the first atom bombs — is an impressive work of cinematic art. It is both visually striking and presents a nuanced view of its subject matter.

But it’s far from clear just what sort of historical lessons the many millions of people who see it will draw from the film’s narrative, which focuses on Oppenheimer’s complex personality and regrets about his achievement, in addition to the postwar effort to purge him from the American nuclear program by those who doubted his loyalty.

That’s why I found it interesting that at the same time that Nolan’s three-hour-long epic was packing audiences into multiplexes, a documentary about one of the people who worked on Oppenheimer’s Manhattan Project team was being shown in arthouse theaters around the nation. Steve James’s “A Compassionate Spy” won’t be seen by a fraction of those who will be drawn into theaters by the “Barbenheimer” hype, but it makes for an interesting companion piece to the more popular film. It is both an affectionate memorial and polemic in favor of the actions of Ted Hall, an American Communist and Soviet spy who handed over to the Stalinist regime a vast and significant store of information about the American nuclear effort.

Taken together, the two films give us two differing views about how contemporary popular culture wants viewers to think about the history of the American nuclear project as well as the efforts to combat communism in the postwar era.

Yet while “Oppenheimer” is not as dishonest or propagandistic as “A Compassionate Spy,” it’s also true that neither comes close to a full understanding of the argument in favor of the use of nuclear weapons to force Japan’s surrender. Just as important, they fail to make clear the enormity of the crimes of the government that those sympathetic and presumably idealistic young Americans supported. Nor do they acknowledge the cruel irony of a situation in which so many Jews supported the antisemitic regime of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

It’s possible to argue that none of this really matters today. The Soviet Union is, thankfully, as dead as the Nazi regime it allied itself with and then defeated.

Its crimes and the tens of millions who died as a result of Stalin’s oppression — whether by purges and mass executions or in famines deliberately caused by the brutal leader’s policies, such as the Holodomor, which killed millions of Ukrainians — are remembered only by historians.

And while nuclear weapons remain a threat to human existence, worries about them have also been largely marginalized, made obvious by the blithe willingness on the part of so many supposedly enlightened people to risk an escalation of the Russia-Ukraine war, regardless of the risks to the world.

Still, it would be a mistake to ignore the implications of our willingness to simply sweep these issues under the rug. Dishonesty about American communism, and its slavish and disloyal Stalinism, is important not just because it is a matter of preserving the truth about our history.

It matters because when the efforts of those who justify totalitarian and antisemitic movements are romanticized, the foundation is laid for doing the same thing again for contemporary threats. Just as crucial, it is a mistake to glorify those who denigrate patriots or depict the United States as an irredeemably flawed nation that deserves to be betrayed or its opponents lauded. When we do that, we are assisting those who — for not entirely unrelated reasons — are carrying on the work today of the Marxists of the past.

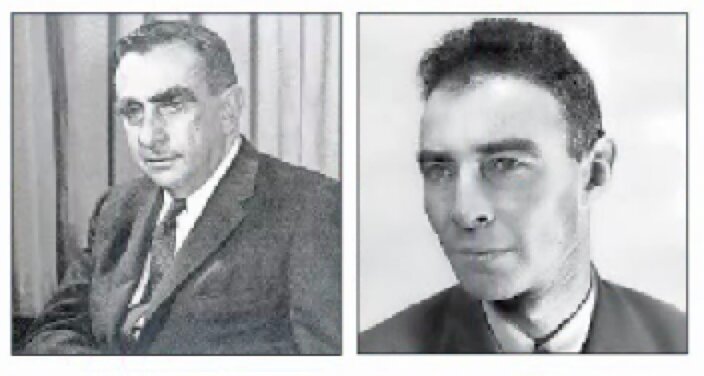

Oppenheimer was a fascinating historical figure whose achievements are worthy of recognition. But there is one glaring mistake about him in both the film and the biography “American Prometheus” by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, on which it is based.

As historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes argue in a must-read article in Commentary magazine, the assumption that the physicist was merely a well-meaning fellow traveler of Communists is wrong. Contrary to his claims of innocence, he was a member of the Communist Party, and he took part in efforts to build support for the Soviet Union prior to its entry into World War II — when it was not only committing mass murder against its own citizens but invading neighboring countries and helping the Nazis.

Klehr and Haynes are the leading experts on the history of Soviet espionage and have written extensively about evidence that has come to light as a result of the opening up of files of the American Venona Project and those of Moscow’s intelligence establishment after the fall of the Soviet Union.

As their work makes clear, far from being American liberals who were just a bit farther to the left than most Americans, the Communist Party USA operated under orders from Stalin’s government. It was a remarkably successful conspiracy that worked to assist the Soviets that, among other things, was responsible for the theft of the Western allies’ greatest secret: the work of Oppenheimer’s Manhattan Project.

Klehr and Haynes rightly argue that the postwar push to strip Oppenheimer of his security clearance was a mistake. By then, he had dropped out of the Communist Party, and so pillorying him for having second thoughts about the bomb was pointless and unfair. But it is equally true that Oppenheimer did everything he could to cover up or lie about his past. As they note, that makes the physicist something of a figure out of Greek tragedy rather than merely a martyr to the excesses of a McCarthyite anti-Communist purge.

Though “Oppenheimer” makes no explicit argument for the Communists who according to his story surrounded him, it does portray them as idealists while those seeking to ferret them out are villains.

That sets the stage for the way the decision to drop the bomb is shown in the film. While the film shows the awesome power of the weapon the scientists built (with the assistance of the US military), as well as its horrifying impact on its victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we are clearly meant to sympathize with Oppenheimer in a crucial scene about his meeting with President Harry Truman in which he sought to get him to share nuclear secrets with the Soviets and to halt further weapons development.

Though he is in only one scene, Truman’s depiction by Nolan is an injustice. He is shown as insensitive and dismissive of Oppenheimer, whom he calls a “crybaby” for speaking of the blood on his hands.

As Truman pointed out, if there was blood on anyone’s hands, it was on his. While he had agonized over the decision to drop the bomb, he understood that it was his responsibility to save as many lives as possible rather than to listen to those in the project who had lost interest in the weapon once the Nazis were defeated.

Doing so saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans who would have died in an invasion of Japan had it been necessary, as well as countless more Japanese, who had repeatedly demonstrated their willingness to fight to the last person rather than surrender. Indeed, Japan’s surrender wasn’t assured even after the two bombs had been dropped.

Another figure not fairly depicted is Edward Teller, the Hungarian Jewish physicist who was delegated to studying the possibility of what became the hydrogen bomb. Teller, who later in life would become an ardent Zionist, was an open anti-Communist. Though reviled in pop culture — the title character of Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove” is thought to be a composite future based on Teller and former Nazi missile scientist turned NASA hero Werner Von Braun — blaming even part of Oppenheimer’s fall on Teller is wrong.

But the ambivalence about the bomb and communism that is shown in “Oppenheimer” is nothing when compared to the pro-Communist and anti-American narrative of “A Compassionate Spy.”

The spy in question was Theodore Hall, a wunderkind physicist who graduated from Harvard at the age of 18 in 1944 and then was recruited to join the atomic effort in New Mexico. An avowed Communist, he passed a treasure trove of nuclear secrets to the Soviets, including the exact plans for the “Fat Man” plutonium bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki.

While the Los Alamos labs were riddled with Communists, no one did more to put the bomb in Stalin’s hands than Hall. But unlike others, including German/British scientist Klaus Fuchs and David Greenglass, a project machinist who passed on secrets to his sister and brother-in-law Ethel and Julius Rosenberg — Soviet agents who were ultimately executed for espionage — Hall was never caught.

Though questioned in the postwar era, he evaded prosecution, largely because exposing him would have hurt his brother Edward Hall, who was helping develop intercontinental missiles for the US Air Force. Eventually, he moved to Britain, where he unrepentantly lived out his life with his family working at Cambridge University.

The documentary is told mostly in the words of his adoring wife, who was also a Communist. It takes at face value his claims that spying for Stalin was the “compassionate” thing to do since the United States was a capitalist oppressor nation that would use a nuclear monopoly to create another Nazi-style Holocaust.

As with some of the characters in “Oppenheimer,” the Halls’ blind devotion to Soviet communism even after the mass purges of the 1930s and Stalin’s 1939 pact with Hitler illustrates both the willingness of so many on the left to delude themselves about Russia as well as the depth of their fanaticism.

That a successful documentarian like James, who is best known for his acclaimed 1994 “Hoop Dreams,” would depict the Halls as heroes rather than as, at best, deluded extremists, ought to be shocking. But it is like so many of the pop-culture depictions of American communism in the last 40 years in which the Stalinists are victims and those who sought to protect American liberty are the bad guys.

Until the fall of the Soviet Union and the Venona revelations were published, the American left was committed to a false narrative about the innocence of people like the Rosenbergs and Alger Hiss, an official in the Franklin Roosevelt administration who was another Communist spy. Once that was no longer tenable, they switched to defending those who worked for Stalin as idealists who deserve our praise rather than opprobrium.

“A Compassionate Spy” is hardly the first such effort not so much to exonerate American Communists as to honor them. It is part of the same genre as, for example, Tony Kushner’s 1991 Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Angels in America” and Ivy Meerpool’s 2004 “Heir to an Execution,” which celebrated her grandparents, the Rosenbergs.

Such efforts are infuriating, but what makes them even worse is the assumption that the backgrounds of people like Hall and Oppenheimer, both of whom were utterly disconnected from their Jewish heritage, somehow made it natural for them to embrace communism.

The same is true for attempts to argue that their efforts should be seen as an effort to counter antisemitism. They opposed the Nazis. But backing the other totalitarian European power put them behind the efforts of Stalin, who also singled out Jews for discrimination, oppression and, had he not died before his plans in the wake of the “Doctor’s Plot” were able to be realized, ultimately mass murder.

Nor is this merely a matter of distorting history.

The same way in which utopian ideals were weaponized on behalf of an evil cause with Communists is now employed by a new generation of leftists who, also in the name of human rights, wage a war against the West. These cultural Marxists target America and now Israel for the same sort of opprobrium and delegitimization that was used against the foes of the Soviet Union.

In this same way, such advocates of intersectionality and critical race theory who consider themselves idealists, including some who are Jewish, now wage an ideological war that, as was true so many decades ago, grants a permission slip to antisemitism rather than fighting it.

“Oppenheimer” is a good film that is, as Klehr and Haynes concede, “reasonably faithful” to history. But we should be wary of anything that soft-pedals the truth about those who embraced a murderous, antisemitic regime. American Stalinists weren’t victims; their legacy should be a reminder to realize that oppression and hate always lurk behind such utopian delusions.

66.0°,

Shallow Fog

66.0°,

Shallow Fog