Chayei Sarah reminds us of our history in Hebron

As Shabbat Chayei Sarah approaches, we are once again reminded of the prominent place of Hebron in Jewish history.

According to the biblical narrative, Abraham’s wife Sarah died in Hebron. As a self-described “sojourner,” Abraham needed permission for a burial site from Ephron, the Hebron landowner. He insisted on paying the full asking price in order to ensure his legal title forever. With the exchange of money for land accepted, Sarah was buried in the cave of Machpelah, where Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Rebekah and Leah would also be entombed. According to the Bible, G-d promised: “To thy seed have I given this land.”

Long before Jerusalem was mentioned in the biblical text as a remote Jebusite hilltop town of little consequence, Hebron had become a holy site. It was there that Jewish history in the Land of Israel began and King David ruled before relocating his throne to Jerusalem.

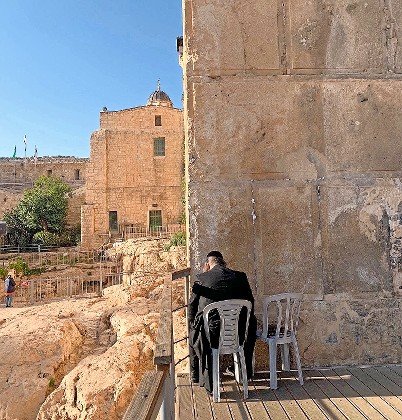

For many centuries, Hebron’s Jews remained a tiny impoverished community under Muslim control, barely able to gather a minyan for prayer. Prohibited from entering the Machpelah enclosure, they could not ascend beyond the seventh step outside the southeastern wall, where they could squeeze messages through a tiny space between the stones.

A Christian visitor described “poor Israelite pilgrims … prostrated, stretching their necks like burrowed foxes in order to try to press their lips against their ancestor’s tomb.”

In the 16th century, Jewish exiles from Spain purchased a courtyard where the Avraham Avinu synagogue was built and still stands. But Jews remained confined to a tiny ghetto, risking harm and even death if they ventured beyond the enclosure. It took another two centuries before the community was significantly enlarged by the arrival of a group of Hasidic Jews.

Over time, Hebron was recognized for its Jewish scholarship and learning. By the mid-19th century, the discoveries of archeologists testified to its antiquity. Yeshivas opened and renowned artists David Roberts and BH Bartlett focused their talents on the majestic Machpelah holy site.

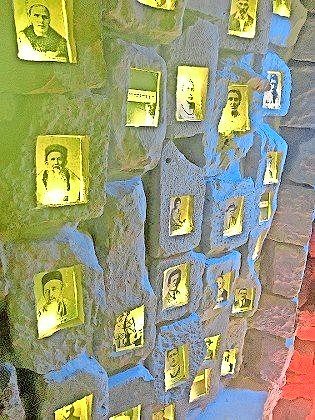

But in 1929, as violent Arab rioting against a growing Jewish presence swept through Palestine, the Hebron Jewish community was attacked and 67 Jews brutally murdered. Once British soldiers removed the traumatized survivors, no Jews remained in Hebron.

In 1948, during Israel’s War of Independence, Hebron was conquered by the Kingdom of Jordan. In the old Jewish Quarter, there were no synagogues or yeshivas. Even the ancient cemetery was desecrated.

But Jews retained an unyielding attachment — identified as “sacred memory” — to the burial site of their patriarchs and matriarchs. Nineteen years later, during the Six-Day War, Hebron was restored to the Jewish people. For the first time in seven centuries Jews could pray inside the Machpelah enclosure at the tombs of their revered biblical ancestors. The following year, a group of religious Zionists led by Rabbi Moshe Levinger came to Hebron to celebrate Passover and begin to rebuild the destroyed community.

Despite devastating Arab terrorist attacks and Israeli government impediments that rarely permitted Hebron Jews to return to abandoned Jewish property, the Jews of Hebron have remained determined to preserve their biblical legacy. They understand, even if others do not, that if Zionism means the return of Jews to their biblical homeland in the Land of Israel, Hebron cannot be excluded.

Shabbat Chayei Sarah in Hebron is an unrivaled experience. A seemingly endless flow of Jews walk down the hill from nearby Kiryat Arba, flanked by Israeli soldiers for protection against Arab terrorist attacks. Inside the massive Machpelah enclosure, they gather in the magnificent Isaac Hall for the reading of the biblical narrative that recounts when “Abraham buried his wife Sarah in the cave of the field of Machpelah, facing Mamre (now Hebron).”

Shabbat Chayei Sarah recounts the precise moment when the attachment of the Jewish people to Hebron and the Land of Israel was forever sealed. It testifies to the enduring power of Jewish history and memory in our promised land.