20 years after Sbarro: Remembering Malki Roth

On the 20th anniversary of the Sbarro bombing, we are again reprinting Rabbi Freedman’s first-person account.

Do we really appreciate all the gifts we have, and how blessed we are even with all the challenges life gives us?

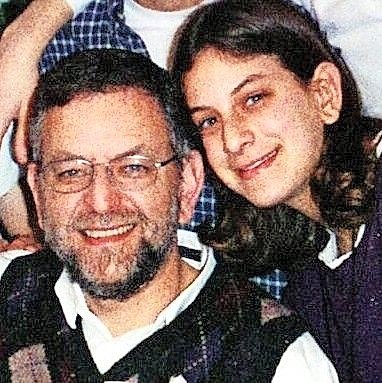

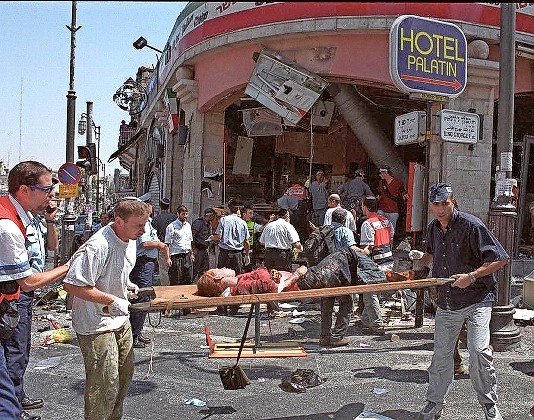

Twenty years ago this Thursday (20 Av 5761, Aug. 9, 2001), a terrorist walked into Sbarro’s pizzeria in Jerusalem and blew himself up, murdering 15 innocent people — including 7 children and a pregnant woman — and wounding 130 others. Malki Roth would have been 35 now, but she remains forever 15 years old, her dreams left in the hearts and minds of those who loved her.

The next day, I penned a letter and sent it to my dad. I’m sharing it now in memory of all those who were lost that Thursday afternoon in Jerusalem.

Friday, Erev Shabbat:

Her eyes, I think, will stay with me forever. Imploring, beseeching, full of so much sadness. I can’t begin to describe all that was in those eyes.

Yesterday, on my way to work, I found myself walking down Yaffo. Hungry, I decided to stop and grab a quick bite at Sbarro’s. In the past five years, I frequented this establishment exactly twice.

Walking into Sbarro, there is a larger area for sitting in the front, but the back looked a bit cooler and quieter, so I decided to grab a seat in the back. That decision saved my life.

When they brought me the baked ziti I ordered, it was cold. I asked the girl behind the counter if she’d mind warming it up. “Ein ba’ayah” (no problem), she said with a smile. I will always wonder if that was her last smile on earth.

A couple of moments later, a fellow from behind the counter came to the back with my baked ziti. That baked ziti saved his life.

Then I both felt and heard a tremendous explosion, and day turned into night. And the screaming began. An awful, heartrending sound; the sound of people coming to terms with a new reality, not wanting to comprehend that life has changed forever.

Those of us in the back were spared. I started yelling at everyone to quiet down, not to panic, and remain in the back; there is always the danger of a second explosion.

Then I smelled smoke and was suddenly afraid the restaurant might be on fire. The ceiling looked like it might cave in, so we started climbing through the wreckage. Would there be another explosion? Would the roof collapse? Were we making the wrong decision?

T

here are no words to describe what the front of Sbarro Pizza looked like in the immediate aftermath of that explosion. A woman was lying near the steps. Her eyes were staring straight at me, so full of pain and longing, sadness and despair. I dropped down beside her, trying to elicit a response. I tried to get a pulse, to no avail. She died there, on the steps, in front of me. She was lying by the table I had decided not to sit at.

There were bodies everywhere. A child’s body under the wreckage, a baby carriage, limbs and a torso, a woman holding a motorcycle helmet and screaming next to a person on the floor.

And then the mad rush to help the ambulance and emergency crews get the wounded out. They were afraid of a second bomb, so there was no medical effort inside beyond getting the wounded on to stretchers and out. A religious Jew missing two limbs, in tears and shock — what do you say?

The wall behind me had shielded me from the blast. Another fellow wasn’t as lucky. Sitting five or six feet to my right, opposite the steps, he caught the full force of the blast and was thrown in the air. When we got him on the stretcher he was bleeding profusely and was missing a leg.

There are no words to describe what his hand felt like, clenched around my arm. He just kept looking from me to his leg and back again. I started saying Tehillim.

I came home last night and gave each of my children a very long hug. But there are so many families today waking up to the reality that life will never be the same. Fifteen funerals, friends and families saying goodbye to those they loved, whose only crime was a desire for a slice of pizza on a beautiful Jerusalem afternoon.

Tonight we celebrate Shabbat. All over Israel, in eight hours, parents will bless their children at the Shabbat table. I imagine we will all hug them a little tighter this week.

In a few hours we will light Shabbat candles. This Shabbat, in the wake of all this darkness, the Jewish people will do what we have been doing for 4,000 years, what we have always done. We will pick up the pieces and light our candles, because that is all we have ever wanted, just to bring a little light back into the world.

After 2,000 years of dreaming, we have come home. So many nations and so many empires tried to stop us from getting here but here we are, nonetheless.

Home. That word has such a beautiful sound to it, for a people that has wandered the globe for so long.

We are not leaving. We will be here to celebrate this Shabbat and next Shabbat, and forever, until the end of time, here, in the hills of Judea and Gush Etzion, and Jerusalem.

M

ay Hashem, who in His infinite Wisdom saw fit to allow me the privilege of celebrating one more Shabbat with my family in the hills of Jerusalem, see fit to put an end to all of this pain and all of this suffering.

Wherever you are, and whoever you are, be with us here, in Yerushalayim, and offer up a prayer for all those who lost loved ones in yesterday’s terrible tragedy.

Yehi ratzon, may it be G-d’s will, that we soon find the road to the peace we have longed for.

After 20 years, what does one take away from such an experience?

The opening of this week’s parsha, Eikev, discusses the rewards we will receive if we will hearken to Hashem’s words. The commentaries point out that the word eikev, which means “as a result of” (ie, as a result of hearkening to Hashem’s words), also refers to a person’s heel, suggesting that one should be careful even regarding mitzvot one might tred on. But why does taking the “easier” mitzvot lightly have such consequences?

Perhaps a meaningful life begins with appreciating the little things, all of life’s seemingly insignificant blessings.

How much would Chana Nachenberg’s husband David give to have a conversation with his wife, who has been in a coma since that awful day? What wouldn’t Shmuel Greenberg give for the chance sit with his child, who was murdered as a fetus along with his pregnant wife Shoshana? That baby would have been 20 today.

Take a moment this Shabbat to appreciate the little things — the chance to give a smile to someone you love, or make the world a little better with one simple act of kindness.

41.0°,

Fair

41.0°,

Fair