Omer count blends space & time, past & present

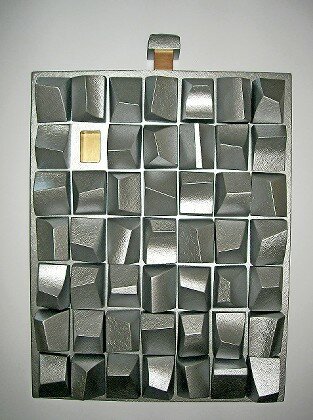

Tobi Kahn grasps an asymmetric block of wood in both hands. He turns the piece, a fluid combination of angles and curves painted a rich metallic pewter, to reveal the base: a perfect rectangle, soft gold and marked with a hand-written number eight. Behind him, 48 similar blocks sit in a wooden grid suspended from the wall.

“I didn’t want each individual piece to look the same because every day is a different day,” he says.

Very much a work of 21st-century art, Kahn’s sculpture is also part of a tradition that stretches back centuries. The Torah commands the Israelites to count 49 days each year, from the second day of Passover until the holiday of Shavuot (which begins this year at sundown on Thursday, May 25). Originally a celebration of the grain harvest in ancient Israel, the seven weeks of Sephirat HaOmer have absorbed additional shades of meaning over millennia of Jewish history.

And they have inspired generations of Jewish artists.

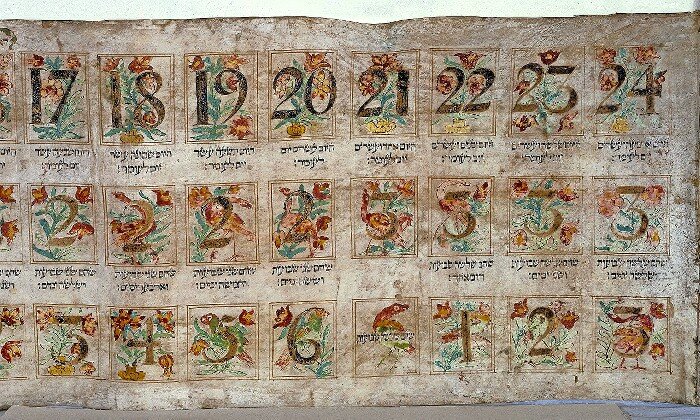

Omer counters have been a staple item of Judaica since at least the 18th century.

“We see so much artistic creativity: paper cuts, books — handwritten and printed — parchment scrolls in calendar boxes,” says Abigail Rapoport, curator of Judaica at the Jewish Museum in New York, which has a large collection of Omer counters, including Kahn’s.

The richness and detail in the counters reflect the meditative aspect of the practice, she notes. “The makers of these calendars are thinking about ingenious methods for counting the Omer and then converging it with a work of art.”

Though the Torah describes it purely as a harvest ritual (omer is the measurement of the barley offering brought at the start of the count), in the Diaspora, Sephirat HaOmer took on spiritual significance.

The fifth-century text “Leviticus Rabbah” describes the Israelites counting 49 days in the desert after the Exodus from Egypt in anticipation of receiving the Torah. In the 16th century, Rabbi Isaac Luria and his disciples connected the seven weeks to seven Kabbalistic sephirot, attributes of Divine revelation, and Sephirat HaOmer became a period of self-reflection and refinement in preparation for receiving the Torah anew on Shavuot.

But Omer counters also reveal the contemporary experiences of the communities that produce them. A parchment counter from the 18th century in the Netherlands depicts the numbers intertwined with tulips — not long after the region’s “tulip mania” — and colorful birds. Portuguese script next to the numbers hints that the counter was made by descendants of refugees fleeing that country’s inquisition.

A counter produced in early 20th-century Rochester, NY, shows a darker aspect of Sephirat HaOmer. The Talmud relates that 24,000 students of the Tannaitic sage Rabbi Akiva perished in a plague during this time, and many Jews observe it as a period of mourning. The intricate papercut counter doubles as a memorial plaque that includes hundreds of names of deceased congregants.

Kahn has been fascinated by Sephirat HaOmer since childhood (his birthday falls during the count), but never saw an Omer counter that inspired him. In 2002, he produced his sculpture, “Saphyr,” which allows the user to count by removing or adding one piece each day. The 49 unique pieces are an expression of his own relationship with tradition.

“I believe in diversity in Judaism,” he says. “I like that there are many types of Jews. I like that each person looks more interesting because of the person next to them.”

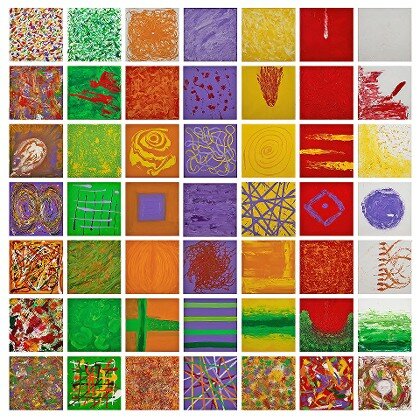

As counting apps and electronic reminders have made traditional counters obsolete, Jewish artists have taken a different approach to Sephirat HaOmer. In 2011, British artist Jacqueline Nicholls began creating a drawing on each of the 49 days, each year focusing on a different theme.

“It’s really slowing down that ritual of counting the day, realizing that the process of time is slow and steady,” she says. “But also, by doing it as a drawing practice, it allows me to grow.”

Nicholls’s first cycle of drawings, “I Am Alive,” focused on small objects she found on the ground; in another cycle, she created intricate geometric shapes out of a single barley grain. This year, she is painting clouds.

Inspired by Nicholls, Chassidic artist Yitzchok Moully, who grew up in Australia, created 49 abstract paintings based on the Kabbalistic interpretation of Sephirat HaOmer. And in 2015, US artist Hillel Smith made a GIF for each day of the Omer that attracted a global following.

Engaging with Sephirat HaOmer as an artist has deepened her appreciation of the counting process, says Nicholls. Her drawings, which blend space and time, are also a way to connect the past to the present: “to engage with the place I am in.”

While counting the Omer, she explains: “My thinking shifts and changes. It’s allowing the time, and that steady habit to build up, allowing Jewish ritual to change me as a person.”

48.0°,

Overcast

48.0°,

Overcast