NYC mural honors man who saved 3,000 Jews

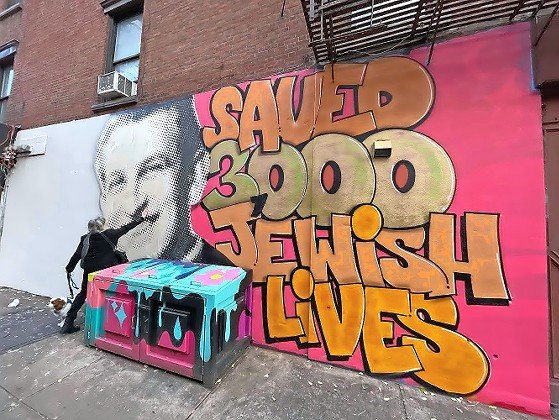

In New York City, antisemites graffiti the walls with Jew-hatred. Last Sunday, though, locals strolling through SoHo saw something else: A mural honoring a man responsible for saving the lives of at least 3,000 Jews.

As part of a series conceptualized by Artists 4 Israel that focuses on the Righteous Among the Nations, New York artist Fernando “Ski” Romero unveiled his mural dedicated to Tibor Baranski, who saved more than 3,000 Hungarian Jews from the Nazis in 1944. The mural debut came, not without coincidence, on the first night of Chanukah.

“There is, of course, the historical aspect of Chanukah, but in modern times, Chanukah has been trying to bring light and goodness to sometimes a very dark world,” Jeremy Goldscheider, an American filmmaker who is producing a documentary on the project, told JNS. “We chose this night because this hero brought light in a dark time.”

Righteous Among the Nations is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who, for altruistic reasons, risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis and their helpers.

Baranski, then only 22, was forced by the advancing Soviets to leave his Catholic seminary in present-day Slovakia and return to his home in Budapest. When Baranski arrived home, he was asked by his aunt, who was raising him, if he could procure fake documents to help save a Jewish family, the Szekeres.

“And he said, ‘Okay, no problem’,” Peter Forgach told JNS of his father. “He just went down to the Papal Nuncio Monsignor Angelo Rotta, the Vatican’s representative in Budapest. And he finagled his way into seeing the ambassador. The fake documents were taken care of in a few minutes.”

Rotta, impressed by Baranski’s cunning and fluent German, recruited him to help with further efforts.

“I think he was in his late ’70s, early ’80s. And he said, ‘Listen, there’s a lot of good that we can do. I just don’t have the energy and you’re young, energetic and fearless. Would you be my right-hand man in this’,” Forgach said of Rotta’s discussion with Baranski, whom he appointed as the executive secretary of the Vatican’s Jewish Protection Movement in Hungary.

In that role, Baranski met with the likes of Raoul Wallenberg, a legendary Swedish diplomat later credited with saving tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from German death camps. In one of his boldest endeavors, Baranski drove a diplomatic car loaned to him by Rotta, a Rolls-Royce limousine flying the Vatican flag, to a factory where nearly 50 Jews who had been baptized as Catholic were being held captive before deportation to Germany, where death would be likely.

Disguised as a priest and using the official automobile and a chauffeur for legitimacy, Baranski told defiant Nazis at the factory gates, “I need this door open. If you don’t open this, I’m going to make a huge scene that’s going to be [heard about] all over the world,” said Forgach. He was bluffing, because I don’t think he had any connections. But the other side didn’t know that. And so they opened up and he started saving the Jewish people at that time.”

Inside, Baranski discovered 2,000 Jews being held captive. After calling out the names of the baptized individuals, he distracted the guards while his assistants gave the remaining Jews information on how to contact the underground.

Over a nine-week period before the Soviets surrounded Budapest, Baranski orchestrated the rescue of more than 3,000 Jews.

Later randomly arrested by the Soviets in order to fill a POW quota, Baranski survived a 16-day, 160-mile forced death march before being left by the side of a house, where a family took him in and helped him recuperate for four months before his return to Budapest to complete his studies. He was later arrested following the communist takeover of Hungary and convicted for conspiracy to spy. He served five years of a nine-year sentence before receiving amnesty.

Baranski became a freedom fighter during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, attempting to garner Western support. Following the failed effort, Baranski escaped to Italy, marrying Forgach’s mother, Katalin Korosy. After starting a school and camp for refugees, the family moved to Toronto, and later to Buffalo, where he lived a quiet life before passing away in 2019.

Baranski was recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in 1979 and was selected by President Jimmy Carter to serve as a member of the US Holocaust Memorial Council.

The mural of Baranski follows two others. The series started last year when Portuguese diplomat and Righteous Among the Nations Aristides de Sousa Mendes was honored in the northern Portuguese city of Vila Nova de Gaia.

“There’s a double-decker bus tour that makes a stop these days [at that mural] for photos. The second one was in Patras in Greece —a huge mural, 10 stories, [that] really transformed the neighborhood. And the amount of media that attention got was incredible,” Goldscheider said of the mural of Mayor Loukas Karrer and Archbishop Dimitrios Chrysostomos.

The mural of Baranski, at the corner of Elizabeth and Spring streets in SoHo, includes a QR code that links to a pop-up video telling the story of Baranski’s heroism.

“We talked a lot within the family many times about his work, and I think he was a very, very religious person. In the Bible, it talks about seeing the image of G-d in the face of every other person,” said Forgach. “My dad said, ‘When I’m looking at a person who has been persecuted, I see the image of G-d there. And I’m obligated to help’.”

48.0°,

Overcast

48.0°,

Overcast