Keeping alive the truth of Babyn Yar massacre

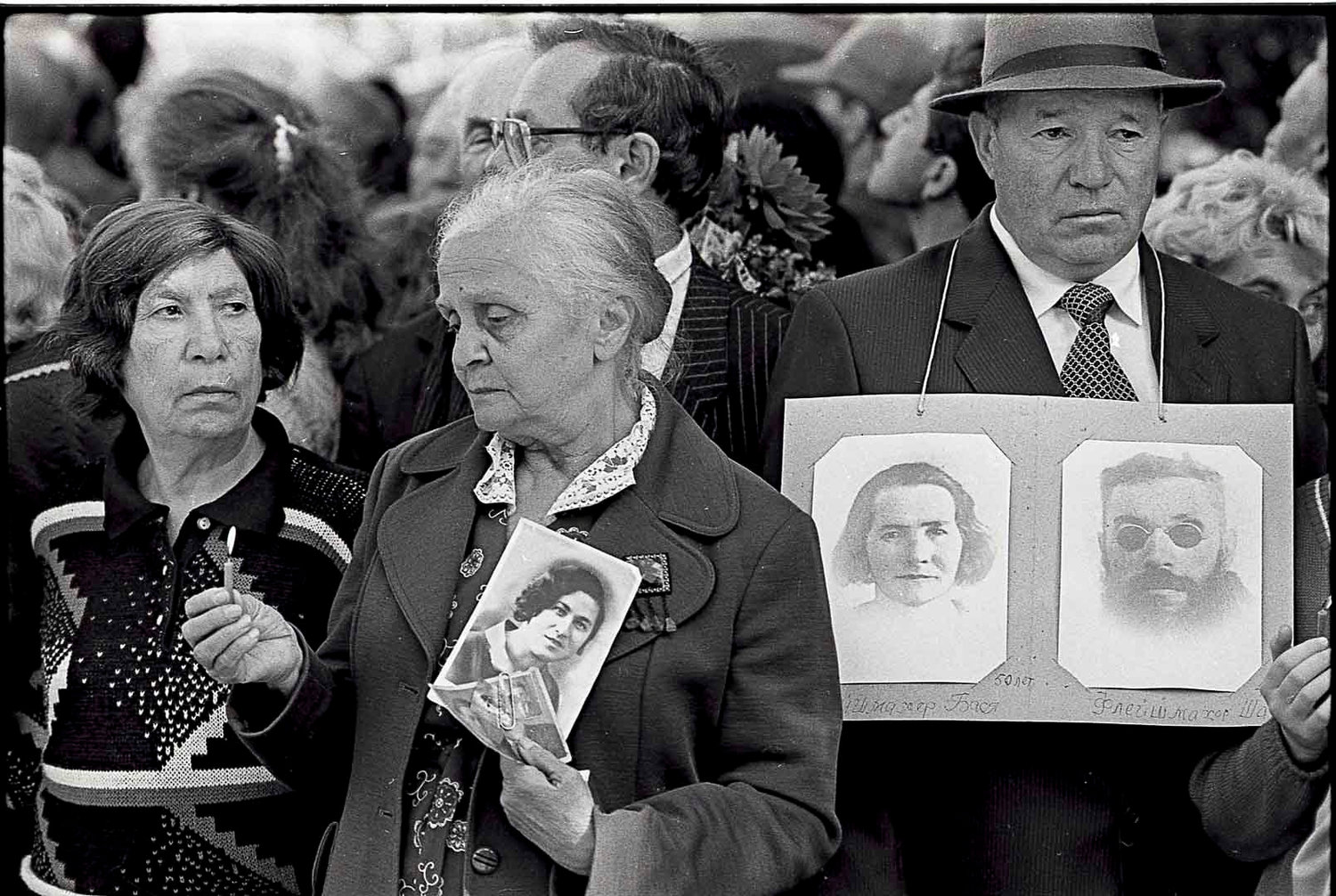

Over two-days, beginning on Sept. 29, 1941, almost the entire Jewish community of Kyiv was wiped out at a ravine on the outskirts of the city known as Babyn Yar (also referred to as Babi Yar).

The Nazis and their collaborators rounded up and shot the 34,000 Jews who had been unable to flee in advance of the Nazi onslaught two weeks earlier, and over the next two years tens of thousands of others, including political dissidents, Roma, psychiatric patients and Ukrainian nationalists, faced death by shooting at the once bucolic site now known as Babyn Yar in Ukraine.

This year, due to restrictions associated with the coronavirus pandemic, the 79th anniversary of the Jewish massacre was marked by an online broadcast featuring Jewish and Israeli leaders, survivors and witnesses of the massacre and the launch of a Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center (BYHMC) audio installation project at the site.

Battles over the appropriate way to preserve memory at Holocaust sites are nothing new; however, efforts to build a memorial and an educational center at the infamous Babyn Yar have been particularly fraught with controversy.

This comes despite the fact that according to Dutch Holocaust researcher Karel Berkhoff, former chief historian for the BYHMC, “Babyn Yar has come to symbolize what has occasionally been referred to as the ‘Holocaust by bullets’ — mass shootings of Jews in Eastern Europe, by contrast with the better known stationary gas chambers used at Auschwitz and other death camps. In the ‘eastern’ Holocaust, the vast majority of Jews were slain in mass shootings, near their homes and within a short span of time — days, weeks or at most months.”

During the decades when the area was under Soviet control, there was no mention of the Jewish victims at the huge, Socialist realism-style official statue that hovered over one corner of the vast ravine. All who perished there were described on the plaques as “victims of fascism.”

Since the establishment of independent Ukraine, Jews are acknowledged, but attempts to create an appropriate official memorial that honors and respects all victims and provides a framework to impart the message of “Never again” have repeatedly stalled.

“There is a reason why every attempt to create a serious memorial at Babyn Yar over the last 30 years has failed,” explained Izabella Tabarovsky of the Kennan Institute in Washington, who said many Ukrainians sought to depict Babyn Yar as “an internal Ukrainian matter” disconnected from the Holocaust.

The latest effort to overcome this attitude came in 2016 with a Declaration of Intent to form the BYHMC, a non-governmental initiative now headed by former Soviet refusenik and human-rights activist Natan Sharansky and funded primarily by a consortium of Russian Jewish philanthropists.

Recently, the BYHMC launched a sophisticated online presence and held a design competition to build a multimillion-dollar state-of-the-art center planned to be operational by 2026. An Austrian architect firm won the competition. Artistic director Ilya Khrzhanovsky is in charge of the final concept and is “in dialogue” with the Austrian architects.

Building on top of the pre-World War II Jewish and Karaite cemetery that lies immediately adjacent to the site of the 1941 mass killings has been one of the major points of contention that have stalled previous attempts at creating a memorial at Babyn Yar. But the map attached to the call for submissions to the design competition clearly shows that the cemetery was included.

Sharansky, chairman of the BYHMC Supervisory Board, assured JNS that under no circumstances would the center build anywhere near the old Jewish cemetery. “We’re not going to dig even 20 to 30 meters away,” he stated.

In remarks to the Kyiv Jewish Forum last week, Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko said that the Babyn Yar property belongs to the municipality and that he sees it “as my mission to implement this memorial.”

Meylekh Sheykhet, director of the Ukrainian branch of the Washington-based Union of Councils for Jews in the Former Soviet Union, who lives in Lviv, has for years fought proposals to build at the site, citing violation of Ukraine’s rigorous Laws on the Protection of Cultural Heritage, as well as Jewish law, because of the cemetery.

One Jewish member of Ukraine’s parliament who wanted further information on the Jewish cemetery issue told JNS she approached BYHMC staff last week and asked to see a map of the site and the building permit. “They told me it was confidential, and I would have to sign a five-year nondisclosure agreement if I wanted to see it. Of course, I refused,” Olga Vasylevska-Smaglyuk of the ruling SN Party said.

Like most Ukrainian Jews, Vasylevska-Smaglyuk had family members who perished during the Holocaust. “The Ukrainian government will never build it,” she said. “There’s no money and not too much interest. Russians give money here for all kind of things, and if they don’t build it, we will have nothing here.”

Izabella Tabarovsky said “this project is our best hope — maybe our last hope — to turn Babyn Yar into a kind of place of memory that the 2.7 million Jews murdered in Holocaust by bullets at sites across those territories deserve to have.”

Sharansky, who was born in 1948 in the eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk, recalls being arrested on his way from Moscow to one of the annual clandestine and illegal memorial gatherings at Babyn Yar in the mid 1970s. “Babyn Yar is a powerful symbol of two things: the ‘Holocaust by bullets’ and secondly, the awful crime of the Soviet regime and their big efforts to erase the memory” of the Jews who were killed.

“My childhood was spent just three miles from other Holocaust killing fields,” he tells JNS. “But we grew up knowing nothing about it.”

Sharansky relates that even as the independent Ukrainian government put a stop to the policy of silence surrounding Jewish victims of the Holocaust, “there has been no serious effort to create any memorials, due to bureaucratic and financial reasons,” he added.

“So, when the mayor of Kyiv and one of the philanthropists approached me” to head the supervisory board of the BYHMC, “it was like closing a big circle in my life.”

Sharansky told JNS that “our funders are first, Jewish international businessmen. They are involved not because … they are from Ukraine and have families who were killed in the Holocaust, some in Babyn Yar. Our board is filled with some of the most respected names.”

They include the first president of Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk; former President of Poland Alexander Kwasniewski; former US Senator Joe Lieberman; former Foreign Minister of Germany Joschka Fischer; and president of the World Jewish Congress Ronald Lauder.

Sharansky believes that the BYHMC should include Ukrainian government involvement, “but not be owned by the government.” He cites the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and Yad Vashem in Jerusalem as examples of entities receiving government funding and input with no government control over museum policy. “We don’t want either the Moscow or the Ukrainian version of the Holocaust to dictate our policy.”

In his meetings with Zelensky, Sharansky says he has invited participation of government representatives to the BYHMC board and is waiting for someone to be appointed.

Meanwhile, as the politics play out, a young and enthusiastic staff of Jews and non-Jews is busy formulating innovative programs to stimulate interest in preserving memory, honoring the victims, and fostering Holocaust education.

Under the direction of artistic director Khrzhanovskyi, the team has initiated projects such as Letters to the Righteous, an effort to reach out to help ease the isolation of the 30 surviving Ukrainians who took part in hiding Jews during the Shoah.

The museum “should be dynamic, modern and tell a story,” says Khrzhanovskyi. “Our task is to convey this story to people living now, so that they feel that this story concerns them. This is important for everyone who lives in Ukraine. This story is not only about how many Jews were killed by the Nazis. It is about humanism, about the events that took place in this country and about which the whole world knows. I believe that this museum will become the hallmark of Kyiv and Ukraine all over the world.”

Nadia Pizharskaya, who manages the Righteous Generation project, is working on the audio installation that was rolled out for the anniversary on Sept. 29 and become a permant exhibition at the BYHMC.

“It’s taking place in the alley,” Pizharskaya said in a Zoom interview. “We picked it because it’s the quietest, cleanest, best-lit place — and then we found out it’s the Jewish cemetery. We didn’t know it beforehand. On each lamp post there will be a different soundtrack, and because it’s the cemetery we won’t be allowed to use any music, so we’ll be reading the names of the victims. Kaddish will also be heard.

“On the next part of the alley, where the TV tower built by the Soviets is on the right-hand side, they took the gravestone of the nearest rabbi and just put it there to remind people that there used to be a cemetery there.”

Pizharskaya, who is not Jewish, says she frequently walks through the area, which is used as a public park, and notes that “the first gravestone you come to is where all the dogs are pissing. People just don’t care. That’s why I want to do this project, just to make them aware.”

48.0°,

Overcast

48.0°,

Overcast