40 years ago, Sadat almost didn’t go to Jerusalem

On March 26, 1979, the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt was signed in Washington. But it almost never happened. President Jimmy Carter tried to scuttle the talks when Anwar Sadat said he would visit Jerusalem. But Sadat ignored the wishes of the American president (and the Arab world) and went anyway, arriving in the Israeli capital 40 years ago this week, on Nov. 19, 1977.

It’s not that Carter didn’t want peace, but he wanted it on his terms. The POTUS was pushing a “Geneva Peace Process” which included all of the Arab Nations, but Sadat felt that the process was all “show” and couldn’t see a way to form a united negotiating bloc with his Arab allies.

For his part, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin wanted to avoid the Geneva conference at all costs. Carter’s Geneva conference would be run by the U.S. and the USSR. Israel would be facing the terrorist PLO, along with her neighbors — including Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Libya, Lebanon and Jordan, mostly Soviet satellites. Add to that the Carter administration’s anti-Israel orientation, and Begin knew the conference would be all of the participants vs. the Jewish State.

Begin wanted bilateral talks and he wanted them with Egypt, which had the strongest Arab military.

So, in late August 1977, Begin went to Romania and asked President Ceausescu for his help, as Ceausescu was close with Egypt’s Sadat. He also sent Moshe Dayan, his minister of foreign affairs, to Morocco to secretly meet with King Hassan and express Israel’s desire for peace talks with Egypt. Eventually that led to secret talks between Dayan and Egypt’s Deputy Prime Minister, Dr. Hassan Tuhami.

Sadat visited Romania shortly after Begin and Ceausescu told him that Begin wanted to make peace. And added, “Begin is a hard man to negotiate with, but once he agrees to something he will implement it to the last dot and comma. You can trust Begin.”

Sadat took the initiative and on Nov. 9, 1977, he delivered a speech to the Egyptian parliament saying that Israel “will be stunned to hear me tell you that I am ready to go to the ends of the earth, and even to their home, to the Knesset itself, to argue with them, in order to prevent one Egyptian soldier from being wounded.”

That speech led Begin government to declare that, if Israel thought that Sadat would accept an invitation, Israel would invite him. Walter Cronkite acted as the go-between. On Nov. 14, Cronkite interviewed Sadat, who confirmed he was willing to go anywhere at any time for a meeting; all he needed was an invitation. Cronkite then interviewed Begin who extended an invitation for the Egyptian leader to come to Jerusalem.

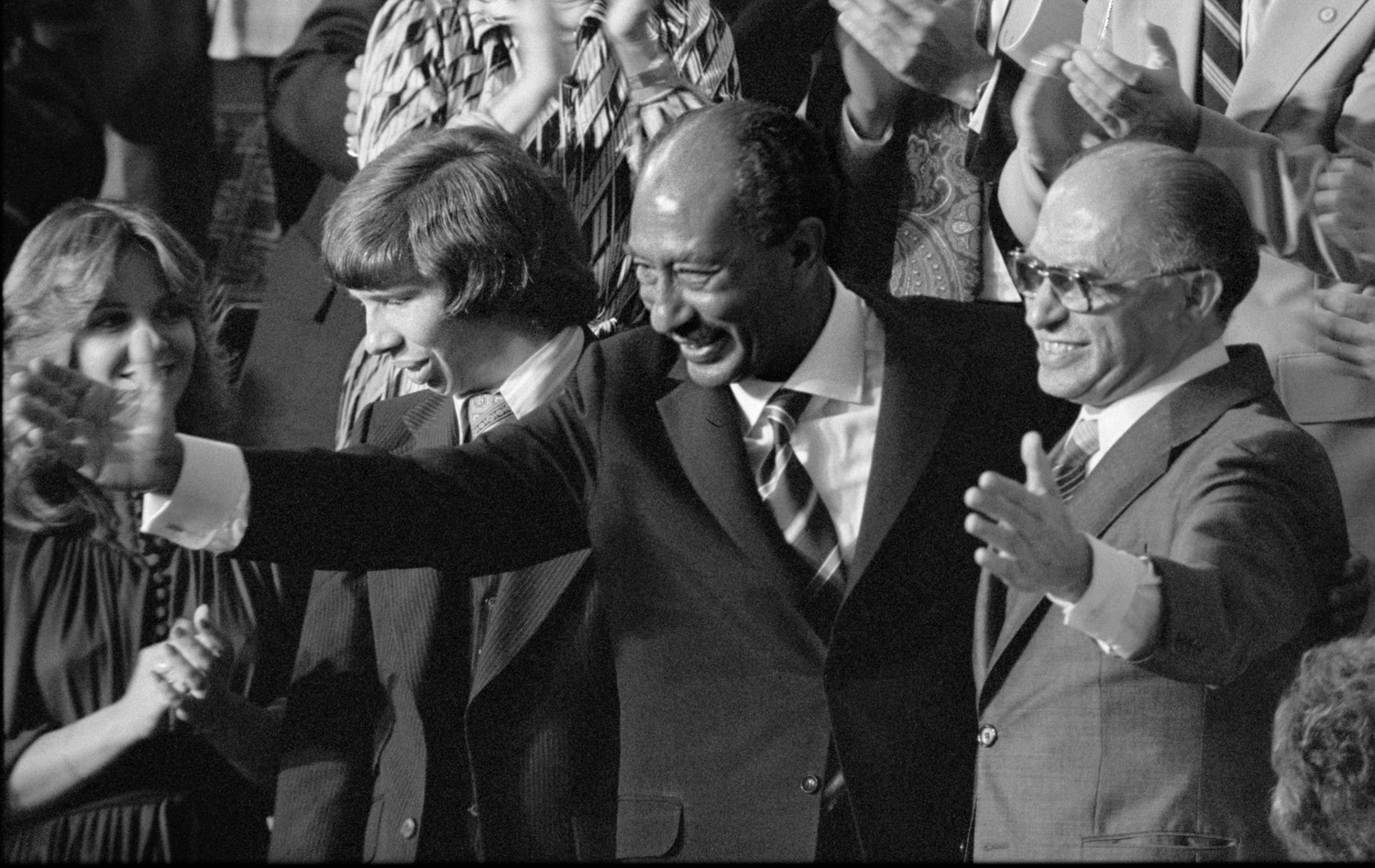

Five days later, Sadat landed in Jerusalem, made a speech to the Knesset and sat with Begin. As the two laid out their opening positions, their staffs began to set up how their bilateral talks would work.

As reported by the Forward, Yossi Alpher, a former senior adviser to Prime Minister Ehud Barak and former director of the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel Aviv University, said that at first Carter was not pleased:

“When Sadat announced he was going to Jerusalem, the Carter administration understood the move as yet another attempt, this time by an Arab leader, to scuttle its scheme to bring everyone together in Geneva. Carter wanted a comprehensive [international] process.” Not only did both Egypt and Israel reject Carter’s internationalization of the process, but Sadat wanted to ease away from the Egyptian-Russian alliance and build a stronger relationship with the U.S.

“By Dec. 1, 1977, three weeks into the Sadat peace initiative, the Carter administration had offered only the faintest approval for the Egyptian president’s visit to Jerusalem, and had not yet abandoned its support for Geneva in favor of the bilateral Egyptian-Israeli process that Sadat, Begin and Dayan were actively proposing.”

The two leaders wanted the peace negotiations to start right away. Sadat suggested to Begin that Israel place a secret representative in the American embassy in Cairo. With American “cover,” the true identity of the Israeli in the Egyptian capital would be known only to the American ambassador in Cairo.

Carter’s acceptance of the proposed liaison scheme would have signaled American backing for Sadat’s unprecedented peace initiative. But Carter said no.

Carter wanted his Geneva talks. He didn’t care that the nascent process begun by Sadat and Begin might lead to peace, Carter wanted his plan or nothing. But thankfully Carter couldn’t stop the approaching peace train. Within days Israeli journalists were allowed into Cairo, breaking a symbolic barrier, and from there the peace process quickly gained momentum. Sixteen months later there was a treaty signing ceremony at the White House.

On Dec. 25, 1977, Begin reciprocated Sadat’s gesture and traveled to Ismailia, Egypt, holding a summit meeting with the Egyptian president. By then Carter had no choice and had to join in on the effort.

Once he got involved, Carter — who had done his very best to screw up what would eventually become the only foreign policy success of his presidency — was instrumental in keeping the talks going. The peace which was signed on March 26, 1979, wouldn’t have happened without him.

47.0°,

Fair

47.0°,

Fair