WWII-era violins keep musicians’ memories alive

After World War II, Palestine Symphony Orchestra musicians who wanted nothing to do with their German-made instruments offered Moshe Weinstein an ultimatum.

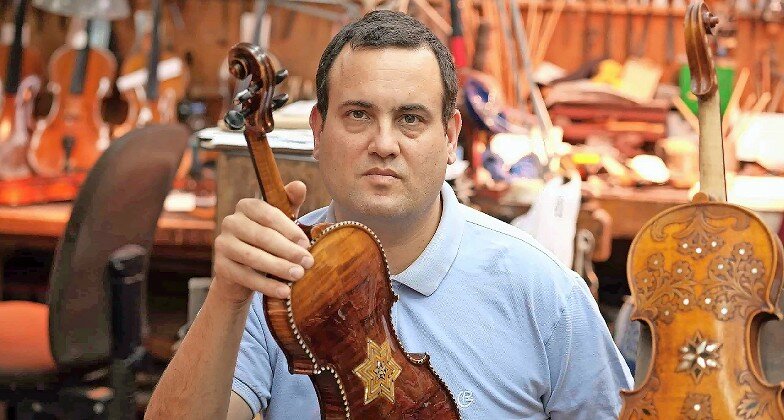

Weinstein had trained as a violinist and violin maker in Vilnius, then part of Poland, and moved in 1938 to Mandatory Palestine, where he opened a violin shop. The musicians told him of the instruments, “Either you buy them, or they will be destroyed,” Avshalom Weinstein, the late violin dealer’s grandson, told JNS.

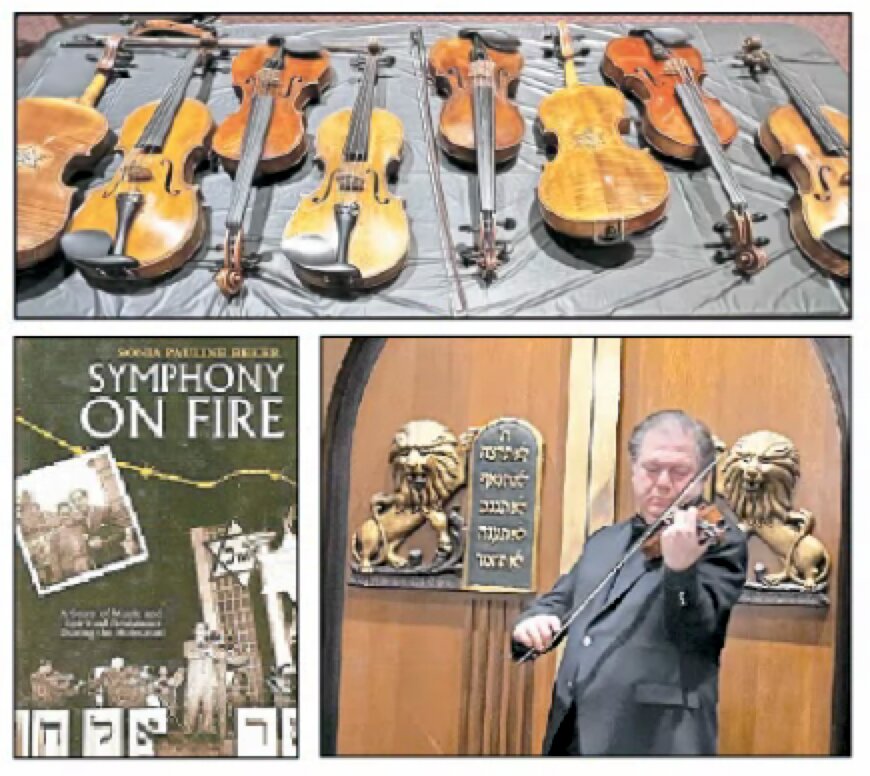

Moshe Weinstein opted to buy, and the instruments he purchased formed the heart of a collection of Holocaust-era stringed instruments, according to the dealer’s grandson. These instruments — along with dozens of others subsequently accumulated — form the heart of Violins of Hope, a project that presents concerts, exhibitions and other educational events around the world, honoring survivors and memorializing those who were murdered.

“The collection started off scrappy, with little documentation and provenance information, then blossomed into a full-fledged collection under the supervision of Avshi Weinstein and his father, Amnon,” the Chicago Tribune reported.

Born in 1909, Moshe Weinstein and one of his brothers were the only two of 11 siblings to survive the Holocaust. Moshe passed away in 1987, his grandson told JNS.

Amnon brought attention to his father Moshe’s instrument collection in a 1999 lecture in Dresden, as well as in an interview that year on Israeli radio. Owners of the instruments and family members of the owners, who heard about the collection in the lecture and on the radio, contacted Amnon.

“It was at that point we understood where these violins came from,” Avshalom told JNS. “Each of these violins tells us a story.”

The Violins of Hope collection now numbers more than 90 instruments. The concerts and exhibitions connected to the instruments honor those who suffered and were killed in the Holocaust, Avshalom said.

The JCC Chicago website lists 65 related events in the Chicago area from April 4 to Sept. 9 connected to Violins of Hope; there will also be events in Pittsburgh in October and November.

During a tour in New York earlier this year, Violins of Hope was invited to Congregation B’nai Avraham of Brooklyn Heights by Sonia Beker, a congregant at the Orthodox shul whose father’s violin is included in the Violins of Hope catalog and was displayed during the project’s visit.

“The violin my dad had loved had been his constant companion since he was a POW,” Sonia said at the event, describing how it was acquired for him clandestinely in 1942 so he could be a member of his concentration camp’s spring, jazz and gypsy orchestras.

“He carried this violin on a German death march of the POWs, stealthily escaping the German guards and then encountering his American liberators in a farmer’s field.”

At a DP camp, Max Beker joined the ex-concentration camp orchestra and met his wife, also a musician. He brought the violin to America in 1949.

Sonia recounted her father’s story in a book, “Symphony on Fire: A Story of Music and Spiritual Resistance During the Holocaust,” published in 2007.

Referring to the project’s collection of violins, Sonia remined that “each violin had an owner — those who survived, and those who didn’t.”

Ilene Uhlmann, director of community engagement at JCC Chicago and Chicago director of Violins of Hope, told JNS that the instruments can make a powerful impression as Holocaust memory “grows dimmer in public memory” every year.

The instruments that are part of the programs relate to varying degrees to the Holocaust. Some belong to Palestine Symphony Orchestra musicians, while others that were found during World War II were named in honor of Holocaust survivors and other noted people, according to Uhlmann.

A “Rabin violin,” for example, is signed but was never owned by former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

“Most of the instruments give little hint of their history, but a few wear it proudly. The back of a violin owned by a prisoner of war bears an ornate engraving of a fortress wall and battlements with the inscription, ‘Souvenir de captivité,’” per the Tribune.

“Several klezmer violins are adorned with Stars of David. In most, if you peer through the instrument’s F-hole, you can glimpse a précis of the instrument’s history, provided by the Weinsteins and usually in English or Hebrew,” it added.

One violin that has been shown and played as part of the project is identified with the late Holocaust survivor and musician Violette Jacquet-Silberstein. (It is listed as No. 100 in a Violins of Hope catalog.) Jacquet-Silberstein’s life was saved multiple times due to her involvement in a concentration-camp orchestra, per the catalog. Her violin, “with its original strings,” is part of Violins of Hope, it stated. The violin is being restored.

“Every story is powerful and an opportunity to change the way people think,” Uhlmann said. “Maybe it will cause people to look at others differently and realize that we are not so different.”

James Grymes, professor of musicology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, met Amnon and Avshalom in 2011, inspiring him to write the 2014 book, Violins of Hope: Violins of the Holocaust — Instruments of Hope and Liberation in Mankind’s Darkest Hour.

A story of Feivel Wininger and his violin stands out, Grymes told JNS.

In the ghetto of Shargorod in Ukraine, a judge gifted an Amati violin — a name, along with Stradivarius, that’s among the most celebrated in instruments — to Wininger, whom he recognized as a talented young musician.

Wininger played the violin at weddings and holidays in exchange for leftover food in a deal he made with a local peasant. He lost the Amati violin but somehow acquired another from the workshop Placht in Schonbach, Germany. The latter violin became part of the Violins of Hope when Wininger’s daughter brought it to the Weinstein shop in Tel Aviv for repair, and the collectors learned its story, the project website states.

“Like I tell my students, each of the 6 million Jews who were killed during the Holocaust have stories to tell,” Grymes said. “These violins are a different type of survivor, and they have stories to tell us.”

50.0°,

Overcast

50.0°,

Overcast