The Kosher Bookworm Pikuach nefesh on Shabbat among American Jews- A Contrast in Generational Response

Saving a life in Jewish law is given very special consideration. According to Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, whose 30th yahrtzeit is this Friday, in his “Handbook of Jewish Thought” states that, “When life is endangered, all religious laws may be totally disregarded.” Regarding pikuach nefesh on Shabbat,

Rabbi Kaplan teaches us that, “Although keeping the Sabbath is considered a foundation of our religion, it may be violated in any manner necessary to save a life. In such a case, it is a meritorious deed to violate the Sabbath, and one who hesitates is guilty of bloodshed.” With this as prologue, let us now consider the following.

My interest in this concept was recently piqued when reading about how the concept of pikuach nefesh was addressed by two American rabbis, both living over a century apart from each other, with each applying Sabbath violation in deference to pikuach nefesh for two radically variant reasons.

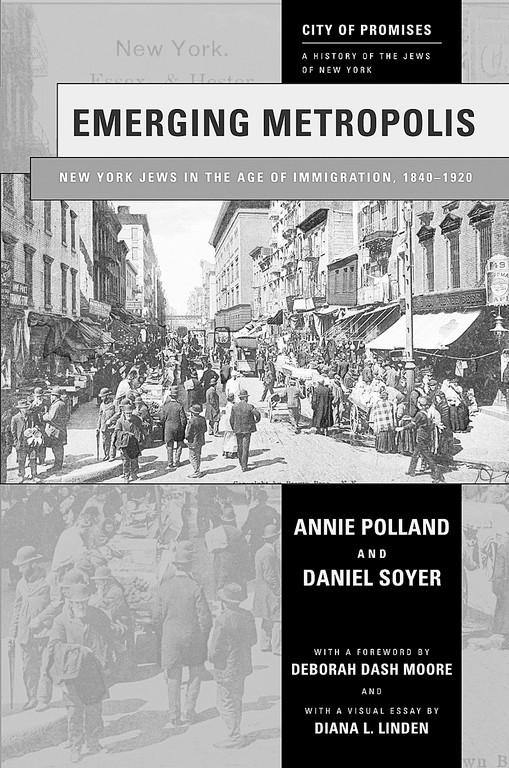

Historians Annie Polland and Daniel Soyer, in their recently published work, “Emerging Metropolis: New York Jews in the Age of Immigrants, 1840 – 1920” [NYU Press, 2012] describe the horrific economic conditions experienced by newly arrived Jewish immigrants in the mid-1800s. One of the first casualties of this experience was Sabbath observance. This was to ultimately define the overall spiritual devastation in Jewish religious observance in America for all time.

Consider the following shocking narrative:

“In an editorial in the Jewish Messenger, an exasperated Rabbi Samuel Myers Isaacs noted that the average Jewish New Yorker desired to keep the Sabbath, but felt that America’s ‘climate’ created ‘something in the air that opposes his intention.’ This pattern held steady. Fifty years later, Rabbi Bernard Drachman, a staunch crusader for Sabbath observance, claimed that Sabbath laxity became significant in the mid 1800s. Immigrants seeking freedom and economic opportunities ‘seemed to think there was something in the American atmosphere which made the religious loyalty of their native lands, and especially the olden observance of the Sabbath, impossible’.”

Further on, Polland and Soyer state:

“To rationalize working on the Sabbath, some immigrant Jews applied the concept of pikuach nefesh – the understanding that one could break the Sabbath to save a life – to Sabbath work for family support. One Orthodox rabbi, Jacob Bauman, even wrote a responsum that used pikuach nefesh to excuse Sabbath desecration by immigrant Jews who worked to support their families [American Jewish History, December 1979]. While most rabbis rejected this interpretation, the immigrant community in America accepted it….So strong was the necessity to work on the Sabbath to feed one’s family, that it could be justified and excused in this way.”

Fast forward a hundred and fifty years to the essay recently published by the Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals, entitled, “Practicing Jews Serving in the National Security Community” by Rabbi Dr. Dov Zakheim. Dr. Zakheim, a musmach of Rav Shmuel Walkin, zt”l, served our nation as Under Secretary of Defense from 2001-2004 and before that from 1985 to 1987 as Deputy Under Secretary of Defense. In these capacities, Zakheim, the first ordained rabbi ever to have served in such a senior government post, came to appreciate the full meaning and impact of pikuach nefesh as it applied to public service and responsibility.

Consider the following contrasting impressions by Dr. Dov Zakheim:

“Exemptions from both biblical as well as rabbinic laws are not limited to government officials when danger to life is concerned. Pikuach nefesh docheh Shabbat – the saving of life trumps even Sabbath prohibitions – is a well-known principle in halacha. How one defines pikuach nefesh is, however, the subject of considerable discussion among halachic decisors.”

“When, therefore, in January 2001, before either of us had been confirmed for our respective positions, Donald Rumsfeld told me that life was always in danger somewhere within the realm that is covered by the Department of Defense, I told him that I could certainly work on my Sabbath when life was truly in danger. On the other hand, I added, if it was merely a matter of attending an ordinary meeting of some kind, such as a staff meeting, that was an entirely different matter. Rumsfeld accepted this explanation without hesitation.”

In viewing this contrast of the Jewish work experience involving chillul Shabbat and pikuach nefesh over a span of 150 years, we mush step back and truly behold how our status within American society has changed over this vast number of years. Both our economic, as well as political status, has gained in both stature and regard from our fellow citizens. Our safeguarding of our religious observances is increasingly gaining the respect of our Christian neighbors, and the witness of these observances by our non-observant fellow Jews is serving as a welcome catalyst to their acceptance by many among them.

Both works cited above deserve your attention. Also, may I take this opportunity to make note, once again, of the 30th yahrtzeit this Friday, the 14th of Shevat, of my dear young friend Rav Aryeh Kaplan, zt”l. A more complete tribute to him and his life’s work will, iy”H, be forthcoming.

61.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

61.0°,

Mostly Cloudy