The Kosher Bookworm: The color blue: It’s part of a Jew’s tradition

The color blue has always played a role in both the religious and political traditions of our faith. This can be seen in the references in the ritual requirements of the mitzvah of Tzitzit in scripture, in prayer, and in ritual practice.

The political application is seen in the blue color component that we see in the flag of the State of Israel, both in the two stripes and the Star of David that serves as the emblematic centerpiece of the flag.

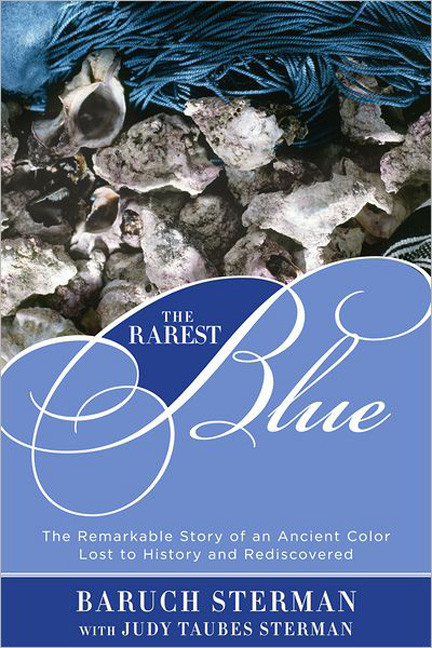

A recently released book titled “The Rarest Blue: The Remarkable Story of an Ancient Color Lost to History and Rediscovered” by Baruch Sterman and Judy Taubes Sterman [Lyons Press, 2012] goes into great historical and technical detail in explaining every facet of the color blue in our spiritual tradition as well as to its role in western civilization.

Especially endearing to me, as detailed in this work, is the role played by the late Chief Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog in the scholarship that helped to clarify our contemporary understanding of this mitzvah. Hopefully, iy”H, a future review will go into further detail on this fascinating saga.

I first came to know of Stermen from a detailed reference by him in a fascinating study published in 1996 by Rabbi Alfred Cohen and cited by Dr. Stephen Bailey in his work, “Kashrut Tefilin Tzitzit” [Jason Aronson, 2000].

In this prior work, Sterman informs us of the historical antiquity of the ritual use of the color blue. According to Rabbi Cohen, “Sterman notes that at the time of the Exodus, te’chelet and argaman [purple] were well-known commodities throughout the ancient world. They are mentioned in the Torah in the list of materials needed for the Tabernacle, and it is generally assumed that the Jews brought these with them from Egypt.”

Bailey, noting the royal use of this color, points out that, “A remnant of this exclusivity is apparent in our contemporary idiom of ‘royal-blue’ or royalty’s ‘blue-blood’.” Humor aside, blue can also express mood both in emotion and in musical mode.

The Torah readings for this time of year give the color blue a high profile. The mitzvah practice itself is self-evident in this past week’s readings, and the midrashic references to Tzitzit and blue in the Korach rebellion are highlighted in two very interesting essays.

The first is by the distinguished theologian from Jerusalem’s Pardes Institute, Rabbi Michael Hattin titled, “Korach and the Garments of Sky-Blue” [vbm-torah.org]. The centerpiece of Rabbi Hattin’s essay is the now well known classic midrashic reading in Bemidbar Rabba wherein we read a deliberately fabricated irony in the following: ”Korach sprang forth and said to Moshe: ‘If a garment is entirely colored with sky-blue techelet dye, is it or is it not exempt from the obligation of tzitzit?’….’If a garment that is colored entirely with sky-blue techelet dye cannot exempt itself, shall four small threads then exempt it?’”

Rabbi Hattin skillfully parses this midrash to lay bare the inner, deeper meaning both as to Korach’s intentions and the reply by Moshe.

As always, Rabbi Hattin’s analysis warrants close scrutiny for the deeper meanings he brings to what otherwise might seem on the surface to be simplistic stories and tales. However, the author cautions us with the following admonition:

“When they read a narrative in the Torah, they [the Sages] paid scrupulous attention to its grammatical structure, to its linguistic nuance and to its major and minor themes.” Read further on in Rabbi Hattin’s teachings for further elaboration on his theme and analysis.

Another essay titled, “Tzitzit and Korah” by Bible Professor Amos Frisch of Bar Ilan University also deserves your time and attention. Prof. Frisch’s essay is predicated on the theme that, “In this homily, the passage on fringes which preceded at the end of Shelach serves as a tool for Korah to attack Moses. We would like to take a closer look at both tzitzit and the Korah story to show how this commandment actually undermines the words of Korah and his followers.” Of major importance to this method are the seven detailed footnotes that give to the author’s thesis a fuller meaning and definition of purpose.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

Given contemporary events stemming daily from our nation’s capital concerning honesty and ethics in government, I would like to bring to your attention a most timely teaching from Dr. Elishai Ben-Yitzhak of Sha’arei Mishpat College, titled, “On Accountability in Public Affairs” [Parashat Hashavua Study Center] based upon the verse from Parshat Korach, “I have not taken the donkey of any one of them.”

To be direst in this matter the author states the following:

“The duty of reporting stems …from the verse, ‘you shall be clear before the L-rd and before Israel’ [Num.32:22]. The Sages deduced from this that everyone in general, and public figures in particular, are obliged to avoid situations which might lead people to talk or suspect them of having exploited their position and used public resources for their personal enrichment or benefit.”

In this regard, the author appropriately cites the timely examples of Garmu and Abtinas and of how scrupulous they were in their service in the Temple as cited in Mesechet Yoma 38a.

And, last, there is the reference from Nechama Leibowitz’ remarks on the crucial stand taken towards those who engage in public service: “Human beings are …petty, suspicious, seeing everything great through their petty vision, ready to slander, to blacken that which shines.” [Iyunim Hadashim Besefer Shmot, page 479]

How true then, and how much is this all the more true, now.

61.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

61.0°,

Mostly Cloudy