The Freifeld legacy

We call it yichus — the legacy of generations of the past. Rabbis, scholars, talmidei chachamim, community leaders who were ancestors to those we now look up to. All the above, Rabbi Shlomo Freifeld, of blessed memory, was not to have. Yichus was to begin with him.

He was born in 1925 into a minimally observant family. His given name was Seymour, but even at an early age he felt the pull of his G-d and his people. By his passing in 1990, he had left a mark upon those whose lives he touched in a manner rarely witnessed in our time.

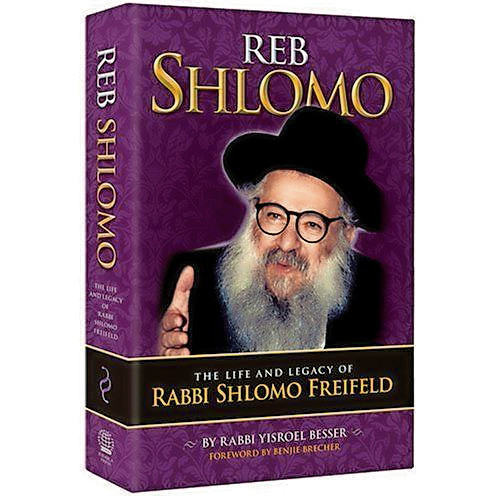

This is the story of his life written using examples of his deeds and teachings as the narrative of his life’s journey. Titled simply Reb Shlomo: The Life and Legacy of Rabbi Shlomo Freifeld, by Rabbi Yisroel Besser, we have over 300 pages of stories of Reb Shlomo’s impact upon the Jewish youth of his time, mid-20th century America.

It was an era that witnessed the devastation of the Holocaust, the founding of the State of Israel and the coming of age of the power and position of American Jewry in world affairs; yet, there was something amiss.

This era soon evolved into a drug culture with rampant promiscuity that enveloped the best of our youth. Through music, poetry, song and dance, our young people of that era, even from the finest of frum homes, with yichus that would impress the best shadchanim, were swept away from their faith, many forever. Rabbi Shlomo Freifeld entered into this cultural fray.

The term baal teshuvah (which Reb Shlomo disliked), was hardly known until the 1960s. Yet this phenomenon was to come forward through the hard work and tireless efforts of Reb Shlomo, and this book is his story.

By 1967, the hippie culture was reaching its nadir, threatening to engulf even our most sacred institutions and families. This was the year that Reb Shlomo established his famous yeshiva, Sh’or Yoshuv, in Far Rockaway, far from the turmoil of urban New York. Within a short amount of time, it evolved into a haven for young boys who, in their eyes and those of others, were castaways from normative Jewish educational institutions.

Reb Shlomo would have none of this. No boy was rejected, no boy was given up on. All “his” boys were given a fair chance to reach their potential no matter how long the road, regardless of the effort required. This book is as much the story of their lives as it is a living tribute to their rebbi’s mesiras nefesh on their behalf.

Within the pages of this biography, we have the story of a young boy who “just had to” go to Woodstock on that famous Labor Day weekend of 1969. How Reb Shlomo confronted that young man upon his return can serve as a stellar example of ahavas Yisrael for all of us. His love definitely preserved this lad’s link to his people in the many years to come.

Another story details how he dealt with the grief that befell another boy when he learned of the passing of his “hero,” Jimi Hendrix, a great rock singer of the era. Reb Shlomo invited the boy to his house that night, asking him to bring a Hendrix record. Together they listened intently to the compositions. Afterward, Reb Shlomo played a classical recording, a rousing symphony designed to lift up one’s spirits, which it did. The contrast was obvious to both.

Afterward, Reb Shlomo gave his evaluation of the recording. “Now I understand why Jimi Hendrix is so popular; the music defined a generation in turmoil,” he said. “You should know that it is disturbing music, indicative of struggles and discontent.”

The boy’s reaction was telling: “That was all he said, but his message penetrated.” That was the genius of Rabbi Freifeld.

According to one former rebbi of the yeshiva, Rabbi Freifeld was venerated by his students, and he in turn never gave up on them. He was a disciple of Rav Yitzchok Hutner of blessed memory, yet he was a devoted fan of the writings and teachings of Rav Avraham Yitzchok Kook zt”l. He was an avid reader of the New York Times, especially its book review section, and had a deep appreciation for the teachings of Chabad. Yet despite everything, the center of his life and his mission was his holy work with baalei teshuvah. Nothing was to come between him and his boys.

In our own community he was the inspiration for Rabbi Moshe Weinberger to establish Aish Kodesh in Woodmere, whose devotion to the teachings of Rav Kook echo that of Reb Shlomo. The awesome presence of the yeshiva, on its sparkling campus in Lawrence, is eloquent testimony to the continued legacy of Reb Shlomo’s activism.

On a personal note, I met Reb Shlomo on Sunday morning, June 22, 1986, after davening at his beis midrash on Central Avenue in Far Rockaway. We were introduced by one of his devoted followers, Robert Dornbush of Bayswater, who knew that I wanted to meet him. We talked for a while, much of our conversation centering upon the national tragedy that had engulfed our nation a few months before. On a cold winter morning in January at Cape Canaveral, the Challenger shuttle exploded upon liftoff, killing seven astronauts, among them Dr. Judith Resnik, a cousin of Rabbi Freifeld.

This book is not a biography, in the traditional sense. It is a story, a series of stories, each designed to teach us the important lesson of ahavas Yisrael. I hope and pray that it will be a lesson well learned by all who read it and share its message.

BOOK EXCERPT

One of the most interesting episodes in Sh’or Yoshuv history is the much-discussed encounter between the celebrated secular singer Bob Dylan and Reb Shlomo.

There was a young baalas teshuvah who had grown close to Rebbetzin Freifeld, and when she found her match, the yeshiva hosted a sheva brachos for her. Among the guests that she invited were two colleagues from her previous life, Bob Dylan and the poet Allan Ginsberg.

The way that Reb Shlomo dealt with the visit of the pop music icon to his Yeshiva taught his boys much about his outlook on that world. One of those talmidim recalled that day.

“To us, Bob Dylan was more than just a celebrity. We lived with his music; he was larger than life and Reb Shlomo knew that. Yet Reb Shlomo called me in before the sheva brachos and informed me in no uncertain terms that there would be no adulation or admiration for the singer whatsoever.

“‘This is a yeshiva,’ he said, ‘and here we give respect to talmidei chachamim, not rock singers.’

“Reb Shlomo told me that, as a big, strong boy, I was in charge of ensuring that no reporters would be allowed in. He also instructed the bachurim that they were not to approach Dylan for an autograph. He told us that we should all say hello, we should all be polite, but nothing that smelled of hero worship would be tolerated.”

The participants in that sheva brachos will never forget the evening. There, in the hot, crowded yeshiva dining room, they sat for hours: Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg, two Yiddishe neshamos who had been swallowed up by the decadence and hedonism of American culture.

They were mesmerized as they listened to Reb Shlomo’s speech and were moved by the stirring music of R’ Shmuel Brazil. R’ Shmuel recalls how Reb Shlomo told him to play the niggun to Libi Uvesari Yeranenu L’Kel Chai, composed by R’ Meir Shapiro.

The guests joined the bachurim in spirited dancing and ate the simple yeshiva fare. For one glorious night, the complications of their lives were left outside in the winter night as they encountered true Yiddishkeit.

In the days that followed, Dylan came to speak with Reb Shlomo. One frosty evening, he left Reb Shlomo’s home and commented to a reporter that “it may be dark and snowy outside, but inside that house, it’s so light.”

According to the testimony of some who were involved at the time, the singer offered to host a concert to benefit the yeshiva, an offer that Reb Shlomo refused. He then told Reb Shlomo that he planned to purchase a home in nearby Long Beach and join the yeshiva as a talmid. Reb Shlomo received his idea warmly, but gently told him that the way to become a talmid would be to join the yeshiva completely.

“First spend three months in the dormitory, and then, if you still want to, you can purchase a home in the neighborhood.”

Dylan had trouble accepting the plan.

To a close confidante, Reb Shlomo explained, “He is struggling to find himself, and the only way that the yeshiva experience won’t just be another transitional stage for him will be if it’s done with true ratzon; for that, it has to be difficult for him. The only way this will work is if he has a genuine resolve to make it work; he has to invest something in it, too.”

Ultimately, it proved too much of an undertaking for the singer, and he moved on.

To Reb Shlomo, Bob Dylan was the same as any other Yid who wanted to learn. All he needed was ratzon and he would be welcome.

A version of this column appeared in 2008.

64.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

64.0°,

Mostly Cloudy