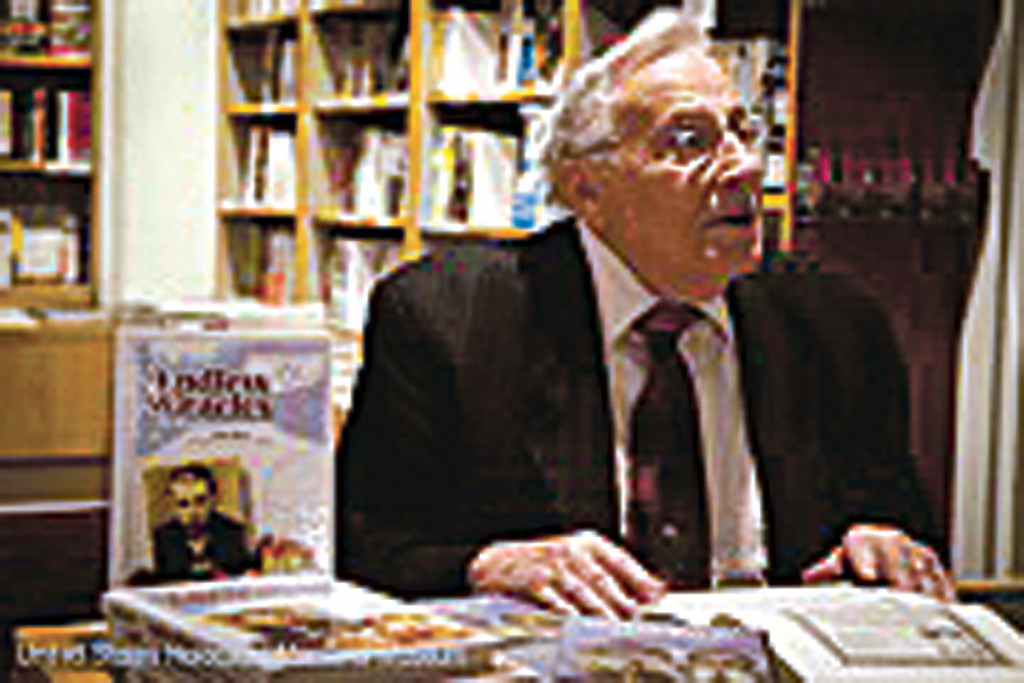

Jack Ratz, Holocaust survivor, teacher, zayda

Jack Ratz is a man on a mission.

The 88 year old Holocaust survivor harnessed his will to survive during the war years in Europe and now continues to muster his strength to tell his story, to speak the truth and educate, to shed light where there is darkness and denial.

He lives in his tidy Brooklyn home, surrounded by comfortable chairs and the mementos of the Shoah, his many laudatory letters from his speaking engagements, awards, certificates of appreciation and treasured photographs of his family, past and present. He speaks with a slight European accent, and stands about five feet tall, barrel chested, an image of strength in spite of some difficulty breathing and walking. His eyes are bright, warm yet worried. He wears a gray knitted kipa proclaiming “supper cool” on his thick gray hair, and clearly, the hand made cards from students across the United States back that up.

Ratz survived the war with his father, but lost an older brother to the war when he fought with the Russian army against the Nazis in Moscow, and lost his mother and three younger brothers when they were shot along with over 30,000 other Jews when the Nazis “liquidated” the Riga ghetto in 1941.

That Ratz survived against all odds and had hair-raising gutsy escapades with miraculous brushes with death are the stuff of movie making. He has told his life’s stories to his children and grandchildren repeatedly over the years; it both colors and frames his life and outlook, as well as those of his children and grandchildren.

“I grew up with the stories all the time, every Friday night,” recalled Dr. Jeffrey Ratz, Jack Ratz’s youngest son. “He was lucky, he took a lot of risks and never got caught.” Jeffrey noted that both he and his wife Pearl are children of survivors and feel that it is “important to carry on their message.” He also said that his son Mathew “spent a lot of time with my father” and that Mathew and Jack “collaborated on reprinting” Jack’s book and Mathew wrote the afterword.

Jack Ratz decided to begin telling his story to wider audiences about 30 years ago when he and his wife Doris, a”h, were at a hotel in Florida. Jack and Doris, he still calls her “my girl,” were married 57 years. “A man came to tell his story of hiding in the Nazi era,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘if he can do it, I can do it.’ I wanted people to now.” He plays a DVD that a school made of his story and sits watching, shaken and tearful. “There are less and less people to tell the story,” he said. “This is my mission.” Since then, he has delivered his message to Jewish and secular schools, synagogues, and meetings. He displays letters of gratitude from students, teachers, administrators, from Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Jack was born in Riga, Latvia in 1925. The Russians attacked Latvia June 1940—a few months later his family celebrated his bar mitzvah in secret. At that time, Jack’s oldest brother was conscripted into the Soviet army. His family never saw him again.

In August, all Jews in the outlying areas were killed. Between then and the end of 1941, the Nazis isolated a ghetto in Riga and segregated a smaller ghetto within the larger ghetto for able-bodied men aged 16 and up. The Nazis then slaughtered the remaining 30,000 Jewish men, women and children in the larger ghetto section, swept it clean of corpses and refilled it with Jews from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia also destined for death. Jack’s mother and younger brothers were killed along with the 30,000. His older brother, hearing of their deaths, was determined to fight the Nazis and was killed in a battle near Moscow.

Jack and his father’s odyssey began at this point. A jeweler in Riga offered to make jewelry from any silver the residents of the ghetto could muster. Jack brought him a silver spoon from his family; the jeweler melted it into liquid, said Ratz, and formed it into a ring engraved with his initials in Hebrew: yud resh—Yakov Ratz—and the date his mother and brothers were killed: 8 XII 41. He wore his silver spoon ring throughout the war. “I wore it all the time,” he said. “Somehow they didn’t see it. It was a miracle. It gave me strength to keep me going.” He holds it as a monument, a tombstone, for his mother and brothers. When his father passed away years later, he died on the same English date that his mother and brothers were shot. Father and son were sent to Lenta Work Camp; while there, Jack was photographed by the Nazis as prisoner #281. Jack’s father worked as a tailor in Lenta; others were shoemakers, machinists, milliners, or repaired cars. Before he was in Lenta, he worked in swamps pulling up roots to dry to be burned as fuel; those working there had a life span of three months, said Jack. He was transferred to Lenta. Jack worked unloading water pipes and then in the kitchen, always on the lookout for ways to increase their chances of survival. In his cubby, he hoarded leftover grease and fat to make into a spread for bread. When a Nazi commandant came in with his dog that sniffed it out and demanded to know what it was, a Jewish doctor confirmed that it was ok and the Nazi let it go. “I could have been killed on the spot,” explained Jack. At one point he stole cigarettes to use as barter for food and another time he found a dead horse that he and others cut up and cooked for food.

In August 1944, Jack, his father, and other prisoners were taken on a death march to Salaspils concentration camp in Latvia. He saw Russian prisoners purposelessly forced to move a mountain, dragging the dirt walking in a figure eight pattern from one place to another. “They died like flies,” said Jack. While there, he saw Jews tortured, put in cages, in lice-infested clothing to see how long they could survive. “At the end they went crazy,” Jack recalled. They were then taken to Stutthoff concentration camp, the first outside Germany and the last liberated by the Allies. Over 85,000 were recorded killed there, but there were many more unrecorded murders of Jews brought in and shot. From there, they were shipped to Burgraben and, in February 1945, taken on a death march to Gottendorf death camp. On March 10, Jack and his father were liberated by the Russian Army, only to be hospitalized with typhoid. They miraculously survived, lying sided by side incoherent and delirious in a hospital bed.

He recalled the triple-decker beds in the work camp, with four inmates on the bottom bunk, three in the middle, three on the top. He recounted one stint of grueling work—“we were full of lice, filth and dirt. We wore our clothes for six months with no possibility of bathing. We walked two hours to the pier, worked from 6 PM to 6 AM and walked back to our barracks by 10 AM only to be ready at 2 PM to walk back.”

In May 1945, the Russians wanted him to be a spy. He “expropriated” a motorcycle and escaped with his father to the American Zone eventually, making his way to the U.S. He later brought his father and his father’s wife (he had remarried). While in Europe, he studied engineering and math and found work in the U.S. repairing televisions and later worked for the MTA. “I always wore a yarmulke,” he stressed. “When you are a mentsh and stick to your principles they respect you.”

Rabbi Shmuel Klammer, a resident of Woodmere and menahel of Shulamith School of Brooklyn, spoke highly of Jack Ratz. “I am very inspired by his ability to maintain his frumkeit,” said Klammer. “I know him for several years. He came and spoke in school. He is incredibly engaging and connected with the girls. He has a zest for life. His story is very inspiring He is good-natured, good humored, warm and personable. He is an inspiration for adults and children.” He sets an example of “emunah and bitachon (faith and belief) and keeping a positive attitude towards life.”

When he speaks to students, he “sizes them up,” he said, shows them a DVD of his life and speaks about his life, about geography and history. He exhorts them, “you are the future. Now you met Mr. Jack Ratz, you have met a Holocaust survivor. Tell your children and grandchildren. Testify that there was a Holocaust. “ He tells them about the Holocaust, how it developed and “what the Nazis did to the Jews. A terrible thing. They killed six million Jews, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers. All G-d’s children. How could they kill them?!”

A flier in Flatbush advertising one of his talks proclaimed “What were you doing between age 14 and 18? Jack Ratz will tell you what he was doing.” “You were in high school,” he said. “Jack Ratz was in a ghetto.”

Inner city children asked him how their “ghetto” differed from his ghetto. He said his was surrounded by three rows of barbed wire with armed guards and anyone leaving would be shot and families were separated and shot to death.

“The message to live by,” said son Jeffrey, “is to live in the world, and appreciate everything Hashem sends us.” As a child of survivors, his outlook is “different than others, not better or worse, just different.”

Jack said that he “went through so much hell that I have no choice but to be religious and raise a family, with children, grandchildren and great grand children to be religious. Look what I have accomplished in life. I came with nothing. You have to have hope, courage, faith in Hashem, be optimistic. I was on a death march; I didn’t expect to live.

“Sometimes when I sit and learn Gemarah (Talmud),” mourns Jack, “I see it happened 2000 years ago that they killed Jews. Now it’s the same thing! Iran is not the only one. One girl (in one of the groups he spoke to) said that she ‘heard it never happened.’ ‘How can you say that!?’ I asked. ‘Where’s my family—who took pictures—the Nazis took pictures! How can you say it never happened?! I was there!”

Mr. Jack Ratz is currently conducting talks on his life in his home and is happy to welcome visitors. He can be reached by calling his cell phone: 646-750-6740.

76.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

76.0°,

Mostly Cloudy