Hey, Sweden, stop torching religious books

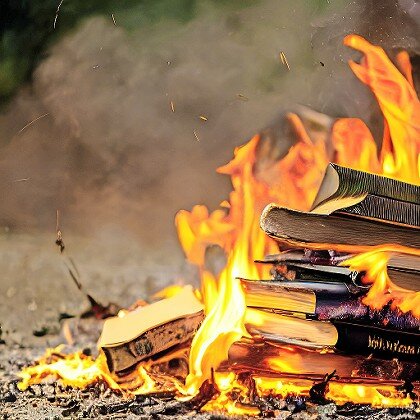

The great German writer Heinrich Heine famously observed in his 1821 stage play “Almansor,” set in Spain during the Inquisition, that “wherever books are burned, they will ultimately burn people.” Nearly a century after his death, the Nazis apparently took Heine’s dictum to heart, staging public book-burning ceremonies that were accompanied by the arrest, brutalization, deportation, and finally, extermination of the regime’s enemies, foremost among them the Jews of Germany.

Both Heine’s insight and the range of books burned by the Nazis — children’s titles like the wonderful “Emil and the Detectives” by Erich Kastner, Erich Maria Remarque’s World War I classic “All Quiet on the Western Front,” novels by Jewish writers like Franz Kafka and Max Brod, works by proscribed thinkers such as Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and, of course, Heine himself—cemented the notion in liberal minds that restrictions upon freedom of speech and conscience are inextricably tied to the most grotesque abuses of human rights. Anyone who has seen the hundreds of titles set aflame by the Nazis that are on display at Yad Vashem, Israel’s national memorial to the Holocaust, cannot but come away convinced that Heine was absolutely, perilously correct.

In our century, however, that logic has been turned on its head. Now, the burning of books has become a symbol of freedom of speech. For those who engage in it, the act of setting the printed word on fire is an affirmation of one’s freedom of conscience, as well as a statement that no book—and therefore no creed or belief system — is too sacred to escape this fate.

• • •

In Sweden, it is the religious books regarded as sacred by their followers that are being lined up for the bonfires of activists who insist that in setting them alight, they are acting in defense of fundamental freedoms.

In January, a provocateur named Rasmus Paludan burned a copy of the Quran, Islam’s holy book, outside the Turkish Embassy in Stockholm, resulting in fury across the Muslim world and potentially jeopardizing Sweden’s bid to join the NATO defense alliance, of which Turkey is also a member. Earlier this month, the act was repeated by Salwan Momika, a 37-year-old Christian refugee from Iraq, who burned the Quran and then stomped on its smoldering pages for good measure.

In the interim, Swedish police have been fielding further requests to burn copies of the Quran in public “as soon as possible,” one applicant demanded. Now, a 34-year-old man who holds both Egyptian and Swedish citizenship is seeking permission to burn the Torah, the five books of Moses that reside at the heart of the Jewish religion, outside the Israeli Embassy in Stockholm, as well as a Christian Bible in the Swedish capital’s Sergels Torg(Sergel’s Square). “Burning holy books is somewhat disgusting, but I am angry and I want to have a debate,” he told the Swedish news outlet Dagens Nyheter.

There is more than a whiff of insanity around all of this.

“I am shocked and horrified by the prospect of the burning of more books in Sweden, be it the Quran, the Torah or any other holy book,” Israeli Ambassador in Stockholm Ziv Nevo Kulman declared on Twitter. “This is clearly an act of hatred that must be stopped.”

Yet the body that could put a stop to the burnings (in the form of Sweden’s judiciary) is actually enabling them, with the country’s Court of Appeals having overturned decisions this year by the police to ban two separately planned Quran burnings.

Is the court in the right here? Can the burning of religious books be legitimately regarded as constitutionally protected free speech?

Here in America, there is little debate on this point. The First Amendment allows us to burn national flags and religious texts, distribute fliers that deny the Holocaust or blame Jews for the COVID-19 pandemic, and wear swastika armbands and other items with a hateful provenance. All of that exists within a culture accustomed to permitting exactly the kinds of speech that most of us find irredeemably offensive.

But in Europe, the combined impact over the last century of communism, fascism and national socialism has resulted in significant restrictions on hate speech; during the pandemic, for example, the authorities in the German city of Munich banned anti-vaccination protesters from appropriating the Star of David, which they did in order to compare their situation with the plight of Jews under Nazi rule. In addition, the debate has been heavily colored by the continent’s experience with Islamist militancy over the past 20 years.

The context was set in 2005, when the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a series of cartoons satirizing the Prophet Muhammad, in violation of the Islamic principle that the founder of the faith should never be represented in artistic form. Ten years later, the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo was the target of a brutal terrorist attack in part provoked by its republication of the same cartoons. (When the magazine resumed publishing after the atrocity, its first cover showed another caricature of Muhammad, this time with a tear droplet in the corner of his eye and the accompanying message “Tout est pardonné” or “All is forgiven.”)

• • •

To my mind, producing and publishing cartoons that satirize or lampoon the core precepts of Islam, or indeed any other faith, is an entirely legitimate act that warrants the protection of the authorities. But burning the Quran, and by the same token the Torah, the Gospels, the Bhagavad Gita or any other holy book, is not.

Here’s the difference. The drawing of a cartoon is a creative act whose goal is to compel the viewer to question their assumptions about a particular topic or to consider that topic in a completely different light, while trying to provoke a laugh, ruffle feathers or both.

Sure, not every cartoon will be able to deliver its message and avoid generalized bigotry — caricatures that encourage us to regard Muslims as bloodthirsty terrorists or Jews as shadowy, hook-nosed financiers are sadly inevitable — but in a liberal democracy, it is the responsibility of editors at independent media outlets to exercise proper judgment on such matters, rather than defaulting to the authorities to engage in censorship, as is the case in most Muslim countries. In other words, we don’t want or need the government to tell us what we can or can’t publish.

Not so with book burnings. These are acts of destruction that once more turn Heine’s maxim into reality by sending the message that in burning your sacred texts, we are declaring our intentions towards you. Given that incitement to genocide or ethnic cleansing can never be a legitimate component of democratic debate, the courts can confidently proscribe its advocates without creating a wider precedent. That is what the Swedish authorities must do now.

60.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

60.0°,

Mostly Cloudy