’Céline’ redux? France’s publishing problem

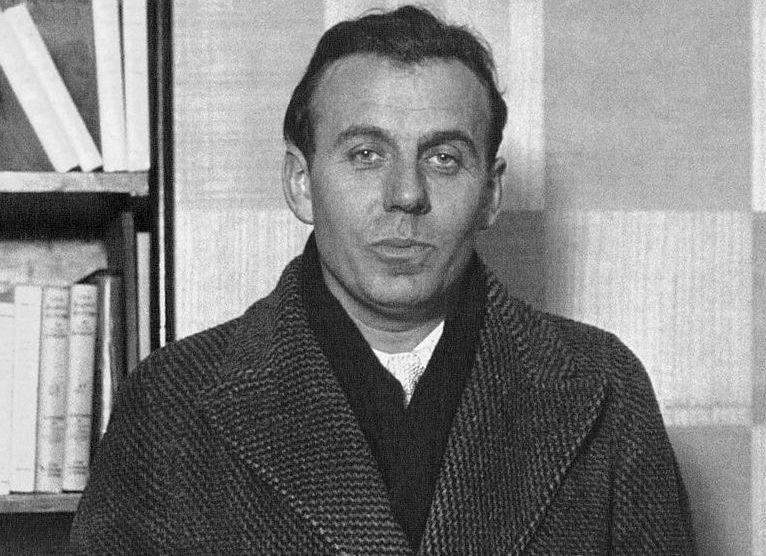

Mention the name “Celine” to most people in the United States—or Europe, for that matter—and they will think you’re talking about the long-serving Canadian pop diva. But among French intellectuals, there is only one “Celine”: Louis-Ferdinand Céline, one of a handful of writers who redefined the mission and style of French literature in the 20th century.

This Céline, whose heyday was in the 1930s, detested the Jews. No surprise there, of course, given the unhealthy number of writers and artists outside Germany who sympathized with the Nazi program for the Jewish people. There were quite a few, after all, in our own language. Take, for instance, the American writer Ezra Pound—regarded by some critics as the leading light of modern English-language poetry—who regaled listeners to his radio show, broadcasted from fascist Italy, with stories “about Jew-ruined England. About the wreckage of France, wrecked under y_d control. Lousy with k___s.”

With cases like these, there’s an inevitable debate about whether one can or should separate the artist’s vulgar hatreds from his or her works of art—rather like the furious arguments lots of Jews used to have about the appropriateness of listening to the operas of Wagner. And every so often, these debates enter the news cycle as ghosts of a past that has again become part of the present. That is exactly what has happened with Céline, at a time when anti-Semitism has re-established itself as a serious and enduring problem in France.

In brief, here is the backstory: Last December, the legendary French publishing company Gallimard announced that it would be reissuing three monstrously anti-Semitic pamphlets written by Céline between 1937 and 1941. When Céline died in 1961—having been condemned as a “national disgrace” for his collaboration with the Vichy regime, with whom he fled to Germany during the Allied offensive of 1944—he left explicit instructions that these pamphlets never be published again.

In fact, they have been, in French-speaking Québec, where the intellectual property rights of these works have expired. But publishing them in France under the imprint of one of the country’s most prestigious publishers is a proposition of an entirely different magnitude.

That was why French President Emmanuel Macron explicitly addressed what has become a bitter domestic controversy in his remarks this week at the annual dinner in Paris of the Conseil Représentatif des Institutions Juives de France, or Crif, France’s Jewish representative organization. In a clever swipe at Poland’s recent draconian Holocaust legislation, Macron pointed out that there are no “memorial police” in France; therefore, these matters are decided by conscience, not law. Macron personally left no doubt that he thought Gallimard should refrain from publishing the pamphlets.

What is the content of these pamphlets that make them so fearful? In 2010, the New York Review of Books carried a feature that revisited the original editions of these works—Bagatelles pour un massacre, L’école des cadavres and Les beaux draps—and quoted from them liberally.

The venom, frankly, is chilling. “The sordid schemes, the betrayals, a nose that points to, lowers toward, and falls over their mouths,” Céline wrote in Bagatelles pour un massacre. “Their hideous slots . . . their filthy k_e grins, boorish, slimy, even in beauty pageants . . . They erupt from the depths of the ages, to terrify us, to draw us into miscegenation, into bloody Talmudic mires and, finally, into the Apocalypse!” Small wonder that the author of the New York Review piece, Wyatt Mason, deemed these texts to be typical of a writer “who, from 1937 to 1944, spent all his flagrant literary energy and aptitude calling—shouting—for the death of every Jew in France.”

By the end of the war, 75,000 members of a pre-war Jewish population of 340,000 had indeed gone forcibly to their deaths. Céline was a direct participant in this genocide, every bit as culpable as the semi-literate French peasant alerting the SS to a Jewish family in hiding to make a few bucks. Reading his words, one hears the sounds of violence: shattering glass, boots on human flesh, the discordant strains of the Nazi anthem, the “Horst Wessel” song. And that is exactly how these words were intended.

One can only hope that Gallimard will heed the advice of France’s president, and abandon its Céline project out if its own volition. There isn’t really a free-speech issue at stake since all these pamphlets are available on the Internet. Thus, the dilemma for Gallimard is whether a publisher of its stature should be distributing anti-Semitic ravings in the name of literary endeavor.

No one could possibly believe that Céline’s words can be read dispassionately in France today, where anti-Semitic attacks of the most brutal kind occur with disturbing frequency. I have written on several occasions in this column about the torture and murder of a Jewish pensioner, Sarah Halimi, in April 2017. To study the account of her ordeal at the hands of a young Islamist intruder is to step into a Céline-like world of hatred, where every word uttered is echoed in physical violence.

Until France rids itself of these paroxyms of Jew-hatred—there was also the torture and murder of Ilan Halimi in 2006; the 2012 massacre of a teacher and three small children at a Toulouse Jewish school; the 2015 hostage situation and slaughter at the Hyper Cacher market in Paris; and much more—it cannot pretend that republishing Céline’s pamphlets is somehow incidental and unrelated to what French Jews are facing now.

59.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

59.0°,

Mostly Cloudy