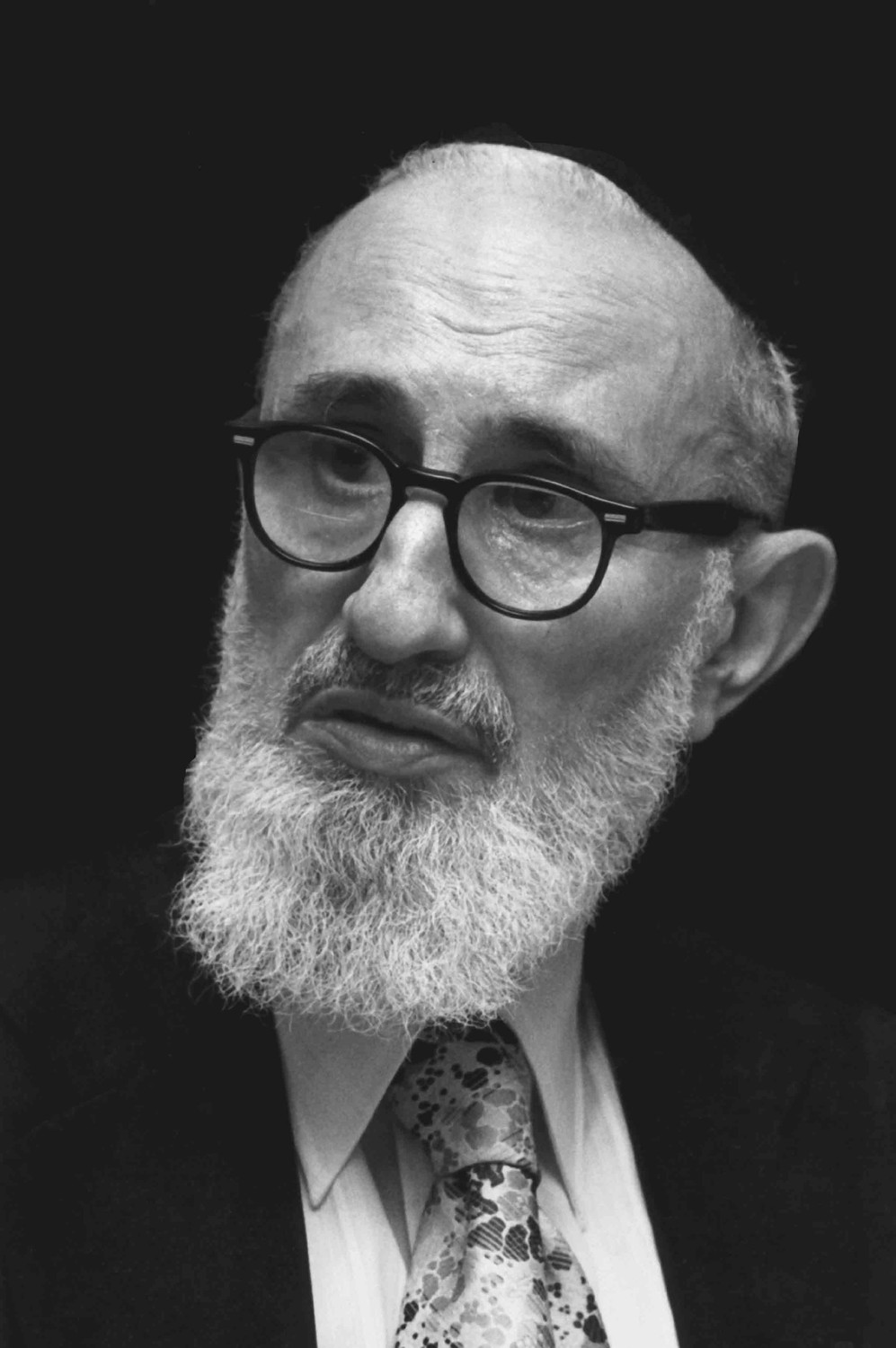

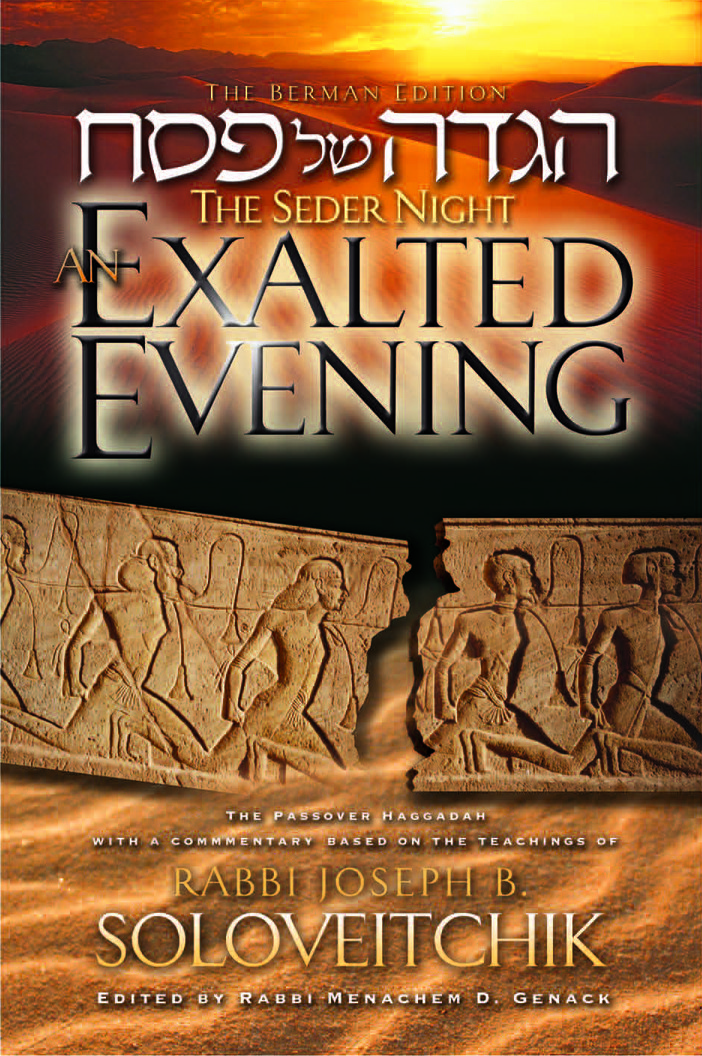

Anticipating an ‘exalted evening,’ with the Rav

Before we consider the Rav’s Haggadah, “The Seder Night: An Exalted Evening,” here are a few heartfelt remarks concerning what Pesach and its rituals meant to the Rav:

“In my experience — that is, in my experiential, not intellectual, memory — two nights stand out as endowed with unique qualities, exalted in holiness and shining with singular beauty. These nights are the night of the Seder and the night of Kol Nidrei. As a child I was fascinated by these two nights because they conjured a feeling of majesty. As a child I used to feel stimulated, aroused, and deeply inspired. I used to experience a strange peaceful stillness. As a child I used to surrender, using language of the mystics, to a stream of inflowing joy and ecstacy. In a word, as a young child I felt the presence of kedushah on these night.” (From “The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik,” by from Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff)

The exalted evening of the Seder is characterized by the themes of the acceptance of G-d’s sovereignty, the transmission of our tradition — the Masorah — and the dynamic and creative force of the Torah she-be-al peh, the Oral Law.

The Rav expressed all these themes in his life’s work. For decades, he taught the senior shi’ur at Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, continued teaching his former students and thousands of others at lectures delivered under the auspices of the Rabbinical Council of America and public shi’urim given at the Moriah Synagogue in New York City, and served as the chief rabbinic figure in Boston where, with his beloved wife Tonya, he founded and continued to direct the Maimonides School.

A rabbinic figure without peer and a seminal Jewish thinker of the twentieth century, the Rav was able to convey to all those who engaged in Torah study with him the immediacy and power of Torah and the experience of Torah as a living force.

For the Rav, the study of Torah was the ultimate path to accepting G-d’s kingship. By infusing the Torah with new insights and fresh approaches, the Rav ensured that Torah would be a continuing source of life that enabled generations of students to experience the eternal connection that every Jew has with Torah, thereby effecting the transmission of the Masorah. Moses is called the “Safra Rabbah de-Yisrael” (the great scribe of Israel), explained the Rav, because he not only wrote the Torah on parchment, but he also effectively inscribed the words of Torah on the hearts and minds of the Jewish people.

The Haggadah says that even though we are all scholars, we are obligated to recount the story of the Exodus and we all must view ourselves as though we personally experienced the momentous events of the Exodus. Rambam echoes this language when he discusses the miżvah of Hakhel, the commandment that the entire Jewish people assemble in Jerusalem once every seven years to hear the King of Israel read to them from the Torah.

He writes, “Even converts who are unfamiliar with the language [of Hakhel] are obligated to listen, with fear and awe, joy and trembling, as the day it was given at Sinai. Even great scholars who know the entire Torah are required to listen with intense concentration, for the Torah established [the miżvah of Hakhel] to strengthen the true creed. One should view oneself as now being commanded and hearing it directly from the Almighty, for the King is a messenger to proclaim the words of G-d” (Hilkhot Ĥagigah 3:6). …

The Rav personified Torah she-be-al peh, its vitality and dynamism, its intellectual excitement and spiritual depth. He also embodied Masorah. As the King was at Hakhel, the Rav was the noble messenger of the Almighty whose entire being was a testament to the transmission, preservation and perpetuation of Torah. He would say that when giving the shi’ur, he felt that Hillel and Shammai, Abaye and Rava, Rashi and Tosafot, the Taz and Shakh were present in the room as he explicated the Gemara. Similarly, when sitting at his father’s Seder, he felt that the Rambam and the Rashba, the Vilna Gaon and Rabbi Akiva Eiger, were invited guests, alive and vital, and active participants in the animated discourse around the Seder table. The Rav inspired his students to join him in this fellowship of learning.

The Masorah, however, can be preserved and transmitted to the next generation only if it is expressed intimately. It was to that endeavor that the Rav brought his extraordinary talents, his genius, integrity, eloquence, and his intense sense of mission and purpose. It was in large part because of his inspired leadership and brilliant pedagogy that we have a religious Jewish community in the United States that is integrated in contemporary society, yet committed to our ancient, glorious tradition, a community that not only observes the precepts of the Torah, but can also still hear the echo of Sinai which reverberates through the generations. …

The obligation of retelling the story of the Exodus on the night of the Seder is more than a recounting of historical events, he explained. Retelling the story of the Exodus must intrinsically encompass the miżvah of Torah study. … The Rav’s teachings emphasized the centrality of Torah study to the Seder night. But the question remains: Why is Torah study so integral to this night?

An understanding of this flows from the Rav’s comments on the miżvah of reciting the Shema, the quintessence of which is kabbalat ‘ol malkhut shamayim, accepting the yoke of Heaven. Rambam explains that a person is required to begin the Shema with the initial paragraph because that paragraph consists of three essential components — “the unity of G-d, the love of G-d, and the study of Torah which is the great principle upon which all else depends” (Hilkhot Keri’at Shema 1:2). …

The Rav’s grandfather Rav Hayim points out that although it is a miżvah to mention the Exodus, Rambam does not enumerate it as one of the 613 miżvot. He explained that Rambam omits it because he considers it not an independent miżvah but as subsumed under the Shema. Remembering the Exodus is an essential part of keri’at Shema because accepting the yoke of Heaven requires our belief in a G-d who is intimately involved in history and human events. That is why the miżvah to believe in G-d states “I am G-d your L-rd, who took you out of the Land of Egypt” (Deut. 5:6) for we affirm our belief in a G-d who cares about the creation and humanity; this is the principle of remembering the Exodus. …

The Seder night is not simply the retelling of an event that occurred in antiquity, but the personal re-experiencing of the event. This concept, observed the Rav, is implicit in the very word “Haggadah,” which can be seen from the phrase “haggadat edut,” a declaration of testimony. One of the basic principles of the law of evidence is that hearsay, testimony known only to the witness through someone else, is not admissible evidence. In this vein, the Haggadah emphasizes that “a person is obligated to see himself as if he personally left Egypt.”

Accordingly, the miżvah of retelling the story of the Exodus cannot be a mere recounting of the chronicle of a historical event. It must be first-hand testimony, an acknowledgement of an event that is in the actual realm of experience of the testifying individual. The Jew who brought his first fruits to the Temple keenly appreciated the contentment and tranquility he enjoyed. Yet this celebrating pilgrim must momentarily transform himself into a victim of the Egyptian slavery … [as he] relives the events of the Exodus.

The bikurim declaration as the foundation of the Haggadah is most appropriate, since both the pilgrim bringing bikurim and the Jew on the Seder night are obligated to re-live and actually experience the Exodus. The sense of immediacy and relevance is a fundamental aspect of Torah study, and that is what the Rav challenged us to recreate at the Seder.

The Torah she-be-al peh enables each generation to uncover novel interpretations and applications. It is not static; rather, it constantly radiates new vistas that bring joy to those who study it. “The orders of G-d are upright, gladdening the heart” (Psalms 19:9). The Rav brought this to all who were privileged to study with him. Alas, it is impossible to fully capture this experience with the printed word — even when the text was penned by the Safra Rabbah de-Yisrael of the last century himself. But our hope is that this work will help readers gain a deeper appreciation of the Rav and his life’s work.

58.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

58.0°,

Mostly Cloudy