Yiddishkeit in unexpected places. 1st stop: Myanmar

YANGON, Myanmar — There was a Chanukah party last month in this former capital city and enough guests — over 200 — to surprise an uninvited tourist.

“There’re no Jews here anymore,” the tourist proclaimed, confused about the celebration at Yangon’s Chatrium Hotel.

“Yes there are,” replied Ari Solomon, a guest from Australia.

“No, they said there are 10 families,” the tourist responded.

“Well, that’s not nothing — that’s 10 families,” Solomon countered. “That’s a lot. You go back to my hometown, Calcutta, and there are lucky to be 16 Jews, let alone 10 families.”

Myanmar’s Jewish community has dwindled to about 20 people. Most of the Jews fled when Japan invaded the country in World War II, distrusted for their perceived political alignment. The majority who remained left in the mid-1960s, when the new regime implemented a socialist agenda that would run the country into the ground.

Still, Sammy Samuels, 38, the de facto leader of the nation’s remaining Jewish community, holds out hope for its future. His father, Moses, maintained the community, opening the door of Yangon’s sole synagogue daily in the hopes of welcoming tourists.

Following his father’s death in 2015, Samuels took over. But Myanmar’s fraught politics — notably the crimes perpetrated by its military against the Rohingya Muslims — are putting his gains at risk.

“[Everyone] thinks that we’re small community [and that there’s] nothing going on,” Samuels said at the Dec. 7 Chanukah celebration. “But we have this kind of event, the government people come — the embassy, friends and family, too.”

The Jewish community here grew rapidly from the mid-1800s through 1942. At its peak, when it was known as Burma, 3,000 Jews called Myanmar home. Jewish restaurants, pharmacies and schools once marked the city’s streets. Stars of David still adorn some buildings.

“My great-grandfather came to Rangoon around the mid-19th century,” Samuels told JTA. A Jewish community soon began to flourish, with many, like the Samuels family, coming from Baghdad, Iraq, in search of prosperity.

Today, the 19th century Musmeah Yeshua Synagogue in Yangon sits solitary in this land of golden pagodas, unguarded in the city’s main Muslim neighborhood.

“People [here] would not understand what is ‘anti-Semitism,’” said Samuels.

The owners of the shops surrounding the synagogue — mostly men wearing traditional Burmese and Muslim clothing — are not hawking Judaica but superglue and paint, among other utility products.

“Five buildings away, we have a mosque. And then right in front of us is the Buddhist temple,” Samuels said.

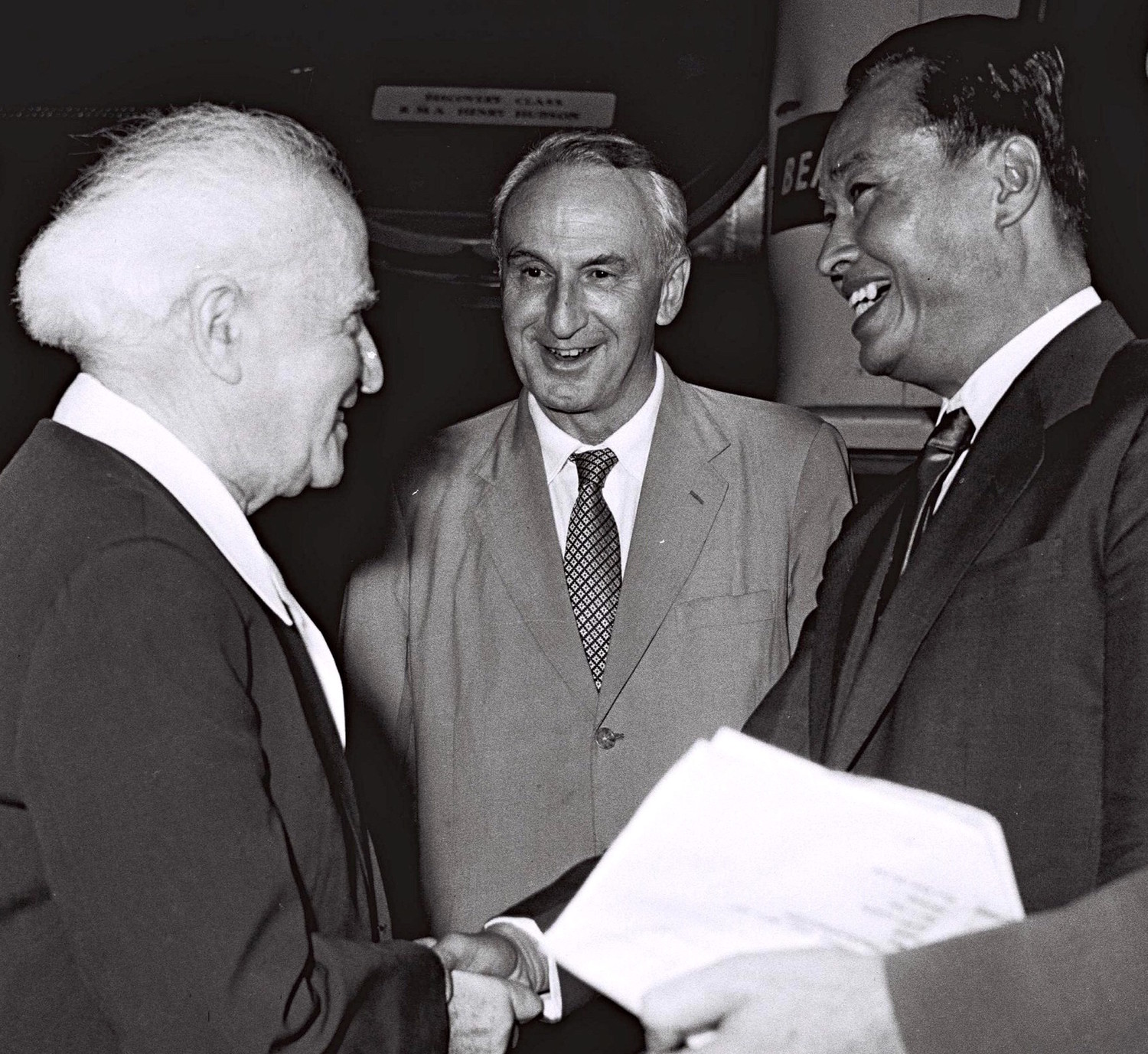

Samuels credits this respect across ethnic and religious groups as directly tied to Israel. Burma was Israel’s “first friend” in Asia, as both countries secured independence from the British in 1948. Burma’s first prime minister, U Nu, had a “soft spot for Israel” and was close with his Israeli counterpart David Ben-Gurion. U Nu was the first prime minister of any country to visit the Jewish state.

“The Burmese population, if you tell them ‘Judaism’ they don’t know, but if you tell ‘Israel,’ they feel like Israel is a religion,” Samuels said. “They fully respect Israel.”

But Yangon’s religious diversity, which has long bestowed Jews with safety, is not reflective of Myanmar at large. The majority of the country remains off limits for tourists due to raging ethnic conflicts; Jews historically lived mostly in Yangon and Mandalay.

In 2016, the Myanmar military ramped up its long-running persecution of the Rohingya, whom most Burmese regard as outsiders and terrorists. The military’s barbarism includes torching villages, throwing babies into fires, decapitating young boys and mass rape. Some 1.1 million Rohingya have fled; thousands are believed to have been killed in what a United Nations investigator called ongoing genocide.

People in Yangon are disconnected from if not outwardly antagonistic toward the Rohingya. Burmese social media is awash with anti-Rohingya posts.

Samuels, perhaps due to his Western education and Jewish understanding of ethnic scapegoating, speaks more empathetically. He even uses the word “Rohingya,” although the Israeli government, in line with Myanmar’s government’s preference, refuses to do the same.

Israel allowed its arms firms to sell weapons to Myanmar’s military through the fall of 2017. In an interview, Israeli ambassador to Myanmar Ronen Gilor declined to comment.

“It’s an unfortunate event,” Samuels said cautiously, likely because of Myanmar’s limited freedom of speech. “We really sympathize with them.”

Samuels opts not to comment on Israel’s arming of Myanmar’s military. He does say, however, that the military’s campaign has caused a decline in tourism.

“A lot of people start to boycott traveling to Myanmar, but when we say tourism, it’s not just about us, a tour company, or the hotel or airline. It involves the tour guide, taxi driver, hotel bellman,” he said. “They should not be punished for what happened. When you come here as a tourist, you see things different.”

Even when Myanmar was a pariah, Moses Samuels had long helped Jewish tourists interested in visiting, answering their queries regarding accommodations, flights and restaurants. Father and son eventually turned it into a business: Myanmar Shalom Travel and Tours.

“Thank G-d, since 2011, the country start[ed] changing unbelievably” and business began “booming,” the younger Samuels said.

This increased business corresponded with a series of reforms pursued by Myanmar’s military junta. The junta even released from house arrest Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Prize-winning human rights advocate who spent nearly 15 years in some form of imprisonment and now runs the country’s civilian government. (She has since drawn criticism for her unwillingness to stand up for the Rohingya, although she has no control over the military.) A photo of Samuels and his family with Suu Kyi is on display outside the synagogue.

Samuels says that since 2011, social media has played a key role in strengthening his community.

“We have a WhatsApp group, ‘Yangon Jews,’” he said. While others in Myanmar have used WhatsApp to encourage violence, Samuels has used the platform for good. Beyond social media, he praises the Israeli Embassy for contributing to Yangon’s Jewish community.

“The Israeli Embassy and us — I would even say it’s a family,” he said.

Gilor echoes those thoughts.

“It’s a very good thing to have collaboration with Sammy and the Jewish community,” the ambassador told JTA, calling the community “a bridge” between Myanmar, Israel and the Jewish world.

Gilor was among the Chanukah celebration’s guests, as was Phyo Min Thein, the chief minister of Yangon. Other leaders, including those from local Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, Baha’i, and Hindu communities, were on hand, too. Two Myanmar Shalom tour groups — one of Israelis and one of Jews with familial histories in Myanmar — accounted for the overwhelming majority of the night’s Jewry.

Solomon, the Australian guest who appeared to be in his 60s, told JTA that his mother was born in Burma. During the Japanese invasion she fled to Kolkata, India. No one from their immediate family had ever returned to Burma.

“My father forbade us from coming back because of the military junta,” Solomon said. Solomon’s mother is 90, so his father finally conceded — partially due to the Samuels-organized tour.

“This my last chance to come and take back videos and pictures while she can still appreciate them,” Solomon said. “This is my only chance. … She came alive once I arrived in Burma and rang back.” Her caretakers “wheeled her around to Dad’s iPad, and we spoke and she was so happy.”

Samuels once pursued opportunities beyond Myanmar’s borders, attending Yeshiva University and working for the American Jewish Congress in New York City. A Jewish visitor to Yangon had helped him get into Y.U. and obtain a full scholarship. Samuels would have been unable to obtain such an education in Myanmar, as universities were closed intermittently for years as part of a military effort to bulwark repeated student revolutions.

“I could’ve moved to U.S. and lived a better life,” Samuels said, explaining why he returned home following his father’s 2015 death. “But our main mission here is very simple: We don’t want any Jewish visitor coming to this country to be a stranger.”

By that measure, the Chanukah event was a coup for Samuels.

“Things change,” he said, recalling years when he celebrated with fewer than 20 people. “A few years ago, no Burmese people knew of Hanukkah. Now the Buddhists wish me on Facebook ‘happy Hanukkah Sammy!’”

And while the synagogue is ranked third on TripAdvisor among Yangon’s “things to do,” there is no minyan without tourists.

Another sign of decay is Yangon’s Jewish cemetery: It is neither computerized nor indexed. In 1997, the government announced its intentions to move the cemetery out of Yangon but never followed through. It remains hidden on a hill that some stray dogs have clearly claimed as their territory; a sign outside proclaims it to be only accessible “with permission from Myanmar Jewish Community.”

Samuels gives me such permission by jotting down a phrase in Burmese on a business card, which I hand to the elderly woman who guards the cemetery and appears to live on its grounds.

Modernity pokes through the cemetery’s historical veneer: A TV satellite protrudes from the caretaker’s home, and her assistant, who smiles and casually watches as I wander the grounds, plays pop music from his smartphone while smoking a cigarette.

Instead of stones placed by visitors, debris comprised largely of shattered gravestones sits atop the few intact graves. As Samuels creates a modern community in Myanmar, the memory of its Burmese predecessor continues to crumble.

This is the first article in a series about the Jews of Southeast Asia.

48.0°,

Light Drizzle Fog/Mist

48.0°,

Light Drizzle Fog/Mist