He’s 93, and we can’t forget

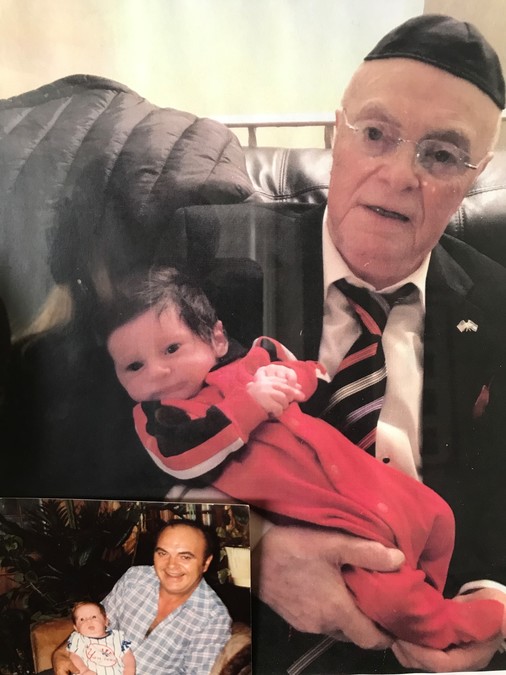

Last March, The Jewish Star reported on the 70th wedding anniversary of Woodmere residents and Shoah survivors Bonnie and Jack Rybsztajn. On the occasion of Jack Rybsztajn’s 93rd birthday on July 12, his story continues.

After the war ended, Jack Rybsztajn was desperate to get from Stuttgart to Brussels, where a few relatives were located. Through two daring voyages on cargo trains, during which he was discovered and arrested, then ultimately given legal residence in Brussels, the couple and their future sister-in-law finally completed the journey. They had headed to Brussels to meet Jack’s sister Cyla, who to their dismay had left for Palestine one day before they arrived.

While in Brussels, the Rybsztajns ate at a kosher restaurant, where they saw a placard on the wall stating that a Mr. Jacobs, with a Brooklyn address, was looking for anyone named RYBSZTAJN who survived. Rybsztajn wrote to this man, saying he is the son of Yechiel Rybsztajn, who had been Mr. Jacobs’ nephew. Not long afterwards, a package containing a tallis and a pair of tefillin was received in Brussels, plus papers authorizing his travel to the United States.

However, “we stayed in Belgium for five years,” Rybsztajn recalled. “The gentile people of Brussels were so nice, which was such a relief after what we went through in Poland. So we stalled coming to America.” He mentioned the Shaydels, a well-to-do couple who welcomed the Rybsztajns into their home and gifted them with nice clothing for their wedding day. This was especially meaningful, as they had no belongings or family.

“Before the wedding, Mr. Shaydel placed a pocket handkerchief in my jacket. To this day I wear one, in honor of that man,” Rybsztajn said.

Amid whispers and rumors of a new war, the couple traveled to Brooklyn in 1950, with the papers that Mr. Jacobs, had provided. The Rybsztajns moved to Woodmere about 40 years ago.

Rybsztajn’s retelling of his experiences — before a videographer sent to his home from Wagner College’s Holocaust Education and Programming Center, run by Dr. Lori Weintrob — was punctuated with periodic sobs of horror and moans of sorrow. Yet at other times, this resilient man was able to smile as he recalled events from his past, as well as affirming his belief in Hashem’s guiding hand.

The following are excerpts from our interview.

Do you remember your bar mitzvah?

Of course, I was a religious boy. I remember a present I got — individual volumes of the five books of Moses, with my name engraved in gold letters on the covers, although I don’t remember who gave them to me.

Were your grandparents there?

Yes. Our families lived close together in nearby towns. We lived in Sosnowiec, which the Soviets renamed Sosnovitz. It was 18 kilometers away from Auschwitz.

Who were your parents?

Yechiel and Yittele. In my town everyone spoke with endearments — I was Yankele, my mother was Yittele, my sister Esther was Estushka. Everyone’s name was an endearment. We lived with my grandparents on my mother’s side, David and Gittele Fiszel (pronounced Fischel), the address was Ciasna #9. The families of my eight uncles and two aunts lived together in my grandparents’ 14-family house.

But anti-Semitism was so big in Poland. Every Friday morning at dawn, my father, who was the president of our synagogue (it was a later burned), took me to the mikvah. Back then not all homes had electricity, many used a liquid called nafta as fuel for their lamps. As we walked to the mikvah, a Pole threw some of this nafta on the beard of a Jew and ignited him with a match. His whole head was on fire. You know what happened to that Pole? They took him in the front door of the police station and let him out the back door. That’s how it was.

Ze’ev Jabotinsky worked with my father to organize Jewish youth to go to Israel. He was a big Zionist, had a lot of influence on the kids. He inspired his brother-in-law, my uncle Ephraim Fiszel, to go, among several hundred other chalutzim, to create the state of Israel on the Exodus boat, which was detained at Cyprus.

What else do you remember about your childhood?

My mother was a real balabusta. I liked everything she cooked; in fact all my four sisters became the best cooks! And my sister Mila, she was so pretty. You know Miss America? Mila would have been Miss Poland if she wasn’t Jewish, so pretty. There was a gentile family that lived in our building as a concierge; we grew up playing with their children and they helped us on Shabbos by adding coal to the fire.

That lady, the concierge’s wife, was still living in our house when my sister Fela went back to Sosnowiec after the war, to liquidate our property. This lady looked out the window and saw my sister coming down the street, and came out of the house so Fela wouldn’t come inside. She crossed her arms and says to her, “So, Felushka, you’re still alive?” My sister just walked away from her.

Tell me about the school you went to.

I went to public school with Jewish children; our town was about 70 percent Jews. And in the afternoons we had yeshiva where we wore yiddishe headloch, special caps with a brim that religious boys wore. I remember how my uncle used to take me to soccer matches; we called it football. The year the HaKoach Jewish team won the championship match, the Poles were so furious that the Polish team lost to the Jewish team that they dismantled the wooden seats and beams of the stadium, just destroyed it, and ran after all the Jews in the town, beating and hitting them with the wooden pieces from the stadium.

What do you remember from the year before the Nazis invaded Poland?

Smaller families ran away out of Poland, but a large one like ours, six children, was not so easy to move.

Poland had a Jewish governance, the Yudenraad, the Germans called it, which kept track of Jewish births, marriages, deaths, etc. It was a great disaster when the Germans came. They took over the governance and had every bit of information on every Jew — addresses, ages, names.

The entrance to the cellar of my grandparents’ house was through the kitchen, it was the place to keep potatoes and things for the winter. My grandfather told the concierge who lived in our house, “I’m going down to the cellar with my wife to hide. After I close the door, put a rug over the door” (to conceal it). We heard the boots marching in and heard “Weisen die Juden?” The concierge, who had lived off the Jews, says in Polish, ”Here they are!” They took my grandparents, the Fiszels, from their cellar to Auschwitz that very first day.

After Poland was occupied, Jews had to walk on our own sidewalk. There was a German police station, not the same place as the Polish police station. I remember walking down Demblinska Street near the German police and one of them calls me, “You there! Come here.” It was easy to see I was a Jew from the yellow star I wore. They made me come every day and shine the boots of the German police and clean the floors of the station.

We had to survive somehow, so my father decided to make a soap factory in the house, and we sold soap. Somebody must have told on us, the Nazis found out and came to the house. I quickly put my father in his bed and covered him with a blanket. When they came in I took the blame for the illegal soap factory and I showed them my father was asleep in his bed. They took me and not my father. But he was a wealthy man, so they stole me for two to three months, and kept me in the jail of the next town while my father paid them. It cost my father everything but he managed to keep me safe.

I was released and went home from the Benjing jail but soon after we had to leave our home and go to the ghetto they created on the outskirts of the town, a suburb of the city called Shrodula (you spell it with a dot over the S). It was very crowded there; we had one room for the eight of us.

There was an ordinance that every boy by the age of 15 must report to the gymnasium, a school which had become a place where they shipped off people to Auschwitz. Leaflets were passed out reading “boys of this age must report” but I didn’t go. I’m not giving myself up, I said to myself. I went into hiding for a few days. They came and took my 7-year-old brother Kalmon [Karolik] instead of me! Then I went to give myself up so they would let him go, I wanted a clear conscience, but they had already sent him off. We never saw him again.

I was tattooed in Auschwitz, so I didn’t have a name anymore, only a number. [Rybsztajn had the tattoo removed years later; documentation he obtained years later showed his number was 124551, and that he arrived at the Langenstein-Zwieberge Concentration Camp, a sub-camp of Buchenwald, in February 1945].

I was a nice husky boy of 15 in 1939, so instead of one bag of cement to carry on my shoulders, they gave me two bags. My father had advised me to tell them I was a tischler, a carpenter, when they took me. He said to be outside was slavery, better to be working inside at a trade. But they didn’t believe I was a carpenter.

I was in so many camps. At one there was a long fence of barbed wire that we marched by every day, and on the other side of the fence were the English prisoners of war, who waved at us. One day some of the POWs threw packages over the fence to us. We moved to pick them up but then we heard bullets and a warning, “stay still.” They arrested us six who had packages in our hands, took our numbers for indentification, and beat us up. I recuperated.

When Yom Kippur came along, we were looking forward to the fast; even with little food, people still fasted. At the end of the day, instead of letting us into the barracks, they made us all go to behind them, where three gallows were erected and facing us. “Remain standing,” was the order, and keep our eyes on the gallows. Three Germans came out and read out three numbers from a file; I was among the first three called. “This and this number committed the crime of obtaining a package of food from English soldiers.” The penalty is to lie on a bench and be whipped, like in a circus. We were bleeding badly, flogged for a piece of bread we never even ate. But the other three numbers committed a capital crime: picking up cigarettes instead of food, and those three were hung on the gallows while we watched. Capital crime. Could easily have been me who picked up the cigarettes instead of the food. G-d wanted me to live!

Continued in next week’s Star.

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy