Crete’s doomed Jewish community is reborn

HANIA, Crete — On Sunday, 263 candles will be lit at an interfaith memorial service at the city’s historic Etz Hayyim synagogue. The names of local Jews who perished during the Holocaust will be read before a delegation expected to include Chief Rabbi Gabriel Negrin of Athens, Greek Orthodox and Catholic clergy, and ambassadors from Italy, Germany and Israel.

Missing will be Kostas Papadopoulos, who may be the last surviving link to a proud 2,300-year Jewish lineage and the tragic military decision that virtually eliminated one of Europe’s oldest Jewish communities.

His story dates back to May 29, 1944, when he was just two years old. On that day, German secret police singled out and rounded up 263 people across Greece’s largest island. All were arrested and carted off to Agia Prison for the crime of being Jewish.

Eleven days later they were forced at gunpoint into the hold of a Greek merchant vessel, the Tanais, set to sail for Piraeus.

“A higher proportion of the Jewish community of Crete was deported by the Nazis than of any country in Europe,” said Rabbi Nicholas de Lange, a professor emeritus of Hebrew and Jewish studies at the University of Cambridge who conducts High Holiday services here.

None of the prisoners would make it to Piraeus and a train bound for Auschwitz. The ship left Heraklion as part of civilian convoy. Near Santorini, a British submarine captain, unaware of the human cargo below deck, ordered the crew to blow up the ship. A direct hit with two torpedoes killed nearly everyone on board.

The sole survivors were half a dozen Cretan Jews who escaped the Germans in May 1944 by hiding with Christian families. Papadopoulos is the last of them, Jewish historians at Etz Hayyim believe.

I recently met Papadopoulos in Heraklion, Crete’s largest city, after a short drive from the ship that brought me to Crete from Piraeus. My overnight journey crossed the same waters where the Tanais and its hundreds of victims remain entombed. Papadopoulos, a dealer and appraiser of fine Christian art, spoke at Daedalou Gallery, his elegant shop in the heart of an upscale shopping neighborhood.

His survival traces back to his Jewish mother Xanthippe’s decision to marry a Christian during the German occupation. After Papadopoulos was born in 1942, his Christian father moved to Athens, leaving his young son with his mother and grandmother. In 1944, when it became clear that the Nazi roundup was imminent, the three of them moved into hiding with a Greek farm family outside Heraklion.

“My mother knew the Nazis were coming,” Papadopoulos said. “Fortunately my family name was Greek, which helped us escape the Germans. It also made it easier to find a family willing to take the risk of hiding us.

“Some of the Greeks who heroically hid Jews were executed as collaborators, but fortunately that was not the fate of the family that protected us. They even returned special paintings we had given them to hide.”

For Papadopoulos, who grew up in Greece and learned his trade as an auction house apprentice in Europe and New York, returning to Crete in the 1970s was not a quick or easy decision.

“People who do what I do, selling religious art, live in places like New York or Switzerland,” he said. “But I wanted to be close to my friends, the people I grew up with.”

One of the challenges that comes with operating a first-class gallery in a place like Hania is the flood of bargain hunters arriving by plane and ship, many of them Germans.

“Customers are used to looking at knockoffs. When they see real art, some believe the prices are too high,” he said.

After cultivating his reputation as an art and antiquities appraiser, Papadopoulos has little patience for customers who try to talk him down.

Several years ago, a towering Chinese tourist made a ridiculous offer of 10 euros for a valuable icon worth far more. Papadopoulos stood his ground, and the angry customer knocked him down. Papadopoulos is still recovering. He says the attack has limited his mobility, making it impossible for him to return for this week’s memorial.

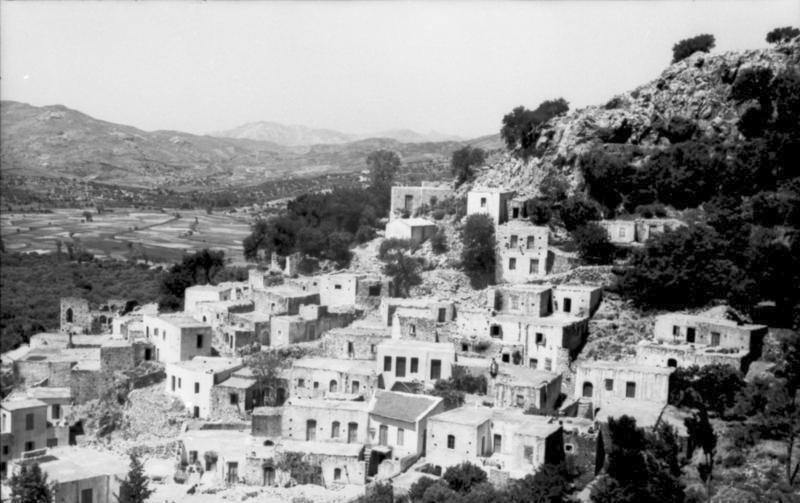

Heraklion’s defunct synagogue was destroyed by the Germans at the beginning of the Battle of Crete in May 1941, but Papadopoulos has eagerly connected with Etz Hayyim in Hania.

The historic sanctuary was looted by the Nazis and fell into disrepair. Years after graves were robbed and the synagogue site became a local dump, an international effort led to its rebuilding under the leadership of the late Nikos Stavroulakis, former head of Athens’ Jewish Museum of Greece.

The reconstruction, completed in 1999, was largely the work of a Muslim and Christian crew from Albania. Rededication led to the creation of a havurah, an interfaith community including Jews, Christians and Muslims enthusiastic about Stavroulakis’ work. He defined Etz Hayyim as a “place of prayer, recollection and reconciliation,” making it open to everyone in the tradition of Hellenistic synagogues.

This fraternity shares common values despite their different religious affiliations. Even a pair of 2010 arson attacks that destroyed many important records failed to slow down the rebirth of this interfaith community supported by donations from around the world.

Anja Zuckmantel, the synagogue administrator at the heart of this week’s event, moved here from Germany 10 years ago.

“Our congregation grows in part because so many Jewish tourists want to come and see what we have done,” she said. “At our summer Kabbalat Shabbat, we have services with up to 60 participants. The number of Jews settling in Crete is slowly but steadily growing. Crete is a beautiful place to live.”

Kostas Papadopoulos may not make it to Hania for the annual memorial service, but he’ll be there in spirit.

One table at his gallery is not for sale. It is covered with Judaica, including a menorah, Torah pointers, a samovar and other heirlooms.

“To be happy,” he said, “I always have to see them.”

54.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

54.0°,

Mostly Cloudy