Where 7 were slain: Neve Yaakov’s US roots

News reports about the Neve Yaakov synagogue massacre have characterized that Jerusalem neighborhood as an “Israeli settlement” located in “predominantly-Palestinian East Jerusalem.”

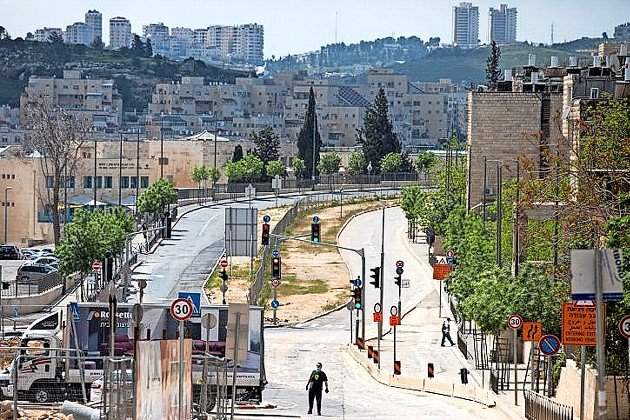

Visitors to the area might be surprised, however, to discover that Neve Yaakov actually is a major urban community with more than 30,000 residents, not at all resembling the stereotypical “settlement” of trailer homes on a windswept hilltop. And far from being some recent foreign implant, Neve Yaakov’s origins reach back nearly a century, to an era long before terms such as “Palestinians” and “East Jerusalem” had even entered our vocabulary, at least in the way they are understood today.

A JTA news brief on Jan. 1, 1924, announced the laying of the cornerstone of a new Jewish settlement by the Mizrachi religious Zionists, just north of Jerusalem’s Old City. The neighborhood would be known as Kfar Ivri Neve Yaakov, after the founder of the religious Zionist movement, the late Rabbi Yitzhak Yaakov Reines. Rabbi Meir Berlin (later Bar-Ilan), president of World Mizrachi, spoke at the event, as did Sir Gilbert Clayton, Civil Secretary of the British Mandatory government.

The new community was located on 16 acres purchased from local Arabs by the American wing of the Mizrachi movement, today known as the Religious Zionists of America. Loans from the movement’s longtime treasurer, Baruch H. Schnur, helped make it possible.

Richard Kauffmann, the renowned German Jewish architect, was retained to design Neve Yaakov. Kauffmann would also become known for designing the cities of Afula and Herzliya, a number of neighborhoods in central Jerusalem, and the residence of Israel’s prime minister.

The role of American Jews in the purchase and development of land in British Mandatory Palestine is a little-known but significant chapter in Zionist history. During the early 1900s, American Zionists in various cities established local “Ahuza” groups to advance these efforts. (In Hebrew, “ahuza” means “holding,” as in real estate holdings.) The St. Louis and Chicago Ahuza branches established the towns of Poriya (1910) and Sarona (1913); the New York branch founded Ra’anana (1921) and Gan Yavneh (1931).

An American Zionist brochure in the 1920s, offering half-acre plots in Neve Yaakov for $150 apiece, emphasized the value of the investment and the opportunity to build a new life, but most of all appealed to those who “want the Holy Land to be in the hands of the Jewish people.”

Neve Yaakov encountered hardships similar to those endured by other Jewish communities in Mandatory Palestine during the 1920s and 1930s. Arab terrorists attacked the neighborhood in 1929 and again during 1936-1939. The British authorities did not connect the town to the national water supply until 1935; another four years passed before it was hooked up to the electricity grid.

Despite these hardships, Neve Yaakov prospered, and by the 1930s boasted a population of more than 150 Jewish families. Neve Yaakov’s farmers became a major source of dairy products for the rest of Jerusalem, and its schools and summer camps attracted students from around the country.

Details concerning the makeup of the community’s population are fragmentary, but it is clear that at least some American Jews not only bought land in Neve Yaakov but settled there as well. The April 1927 edition of Palestine Pictorial, a Zionist advocacy magazine, included a photo of an Orthodox couple kneeling in a field, with the caption, “Springtime Has Come in Palestine: American Jews in Kfar Ivri [Neve Yaakov] planting seed in their garden. Every year sees an increasing number of well-to-do Jews from America settling in Palestine.” Several histories of pre-World War II American Jewish immigration mention the Zelig family, from Philadelphia, living in Neve Yaakov in the 1930s.

The neighborhoods ringing Jerusalem to the north, including Neve Yaakov, were frequent targets of attacks by Arab forces during the 1948 War of Independence. More than a few British soldiers joined in the assaults. During the defense of Neve Yaakov on March 10, Haganah fighters captured two Englishmen who were wanted for their role in carrying out an anti-Jewish terrorist attack on Ben-Yehuda Street in Jerusalem earlier that year, murdering 58 passersby and wounding 200 more. The pair, George Ross and Godfrey Stevenson, were tried by the British authorities for desertion, not terrorism, and then allowed to “escape” to Egypt.

The rapid approach of Arab armies forced residents of Neve Yaakov to flee. On May 17, a New York Times correspondent reported that the Arab troops entering Neve Yaakov included “eight British deserters and one German former paratrooper” — another peculiar feature of the 1948 war.

During the 19 years of Jordanian occupation which followed, the Jews of Neve Yaakov were not allowed to return, or even to visit. Nor were they ever paid compensation for the destruction of their homes, farms and property.

After Israel recaptured the area in the 1967 war, the Jordanian policy of barring all Jews was reversed by Israel’s Labor government, and Neve Yaakov was rebuilt. Eventually it became one of the eight “ring” neighborhoods forming the outer perimeter of Jerusalem, along with Ramot, French Hill, Pisgat Ze’ev, Talpiot Mizrach, Ramat Shlomo, Gilo and Har Homa.

Decades removed from the stereotypical settlements of yesteryear, these communities, with their modern apartment buildings, schools, stores and hospitals, have come to constitute an integral part of Israel’s capital.

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy