Reparations

German ‘blood money’ risked civil war

This is the first in a year-long series of special articles recounting the history of the modern Jewish state in Israel. B”H, The Jewish Star, an unflinching champion of Zionism, the national liberation movement of the Jewish people, looks forward to joining our readers in celebrating the country’s 75th birthday this spring.

Sixty-nine years before the Capitol riot that shocked Washington, Israel went through its own insurrection, on the Knesset.

On Jan. 7, 1952, while lawmakers were debating the Nazi war reparations agreement between Israel and West Germany, a stormy demonstration was taking place outside by opponents of any connection with that country a mere seven years after the end of World War II.

Menachem Begin, then-head of the Herut party, vehemently opposed the move, saying it was tantamount to a pardon of Nazi crimes against the Jewish people. Addressing a crowd of some 15,000 people he gave a passionate and dramatic speech in which he attacked the government and called for its violent overthrow.

The demonstrators began marching toward the Knesset, which was then located in downtown Jerusalem. Policemen, who had set up roadblocks, were unable to control the angry crowd, some of whom managed to reach the doorstep of the parliament and began throwing stones into the plenum hall. The protests were eventually quelled, but not before rioters injured several lawmakers.

Israel was on the brink of a civil war. Then-Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion was intent on striking a deal with West Germany to secure reparations for Holocaust survivors seven years after the camps were liberated and at a time when the death of six million Jews divided the public.

After three days of deliberations, the bill was passed with a majority of 61 (50 lawmakers voted against it). In West Germany, then-Chancellor Konrad Adenauer also faced strong opposition to the payment of any reparations to Israel and the Jewish state with only 11% of Germans having said they believed the country needed to pay such funds.

Opinion polls that were conducted by the Allies in Germany at the time showed that Jews ranked lowest on the list of victims in WWII. The Germans were busy rebuilding their country and negotiating the reparation terms with the Allies for the war damages and saw no reason to compensate the Jews. Audenaur was even sent a letter bomb by Jews who opposed the reparation negotiations.

Against such a charged atmosphere, West Germany began the explosive, sensitive, and complex negotiations with the Allies, all of which were conducted in secret. Separate talks were held with Israel and Jewish leaders of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, or Claims Conference.

After six months of negotiations and several crises, the two agreements were signed at the Luxembourg City Hall by Adenauer, then-Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett, and Nahum Goldman of the Claims Conference. West Germany pledged to pay Israel 750 million dollars in goods and services and the Claims Conference received an initial sum of 107 million dollars for reparations to victims. Both sums were lower than the original demands.

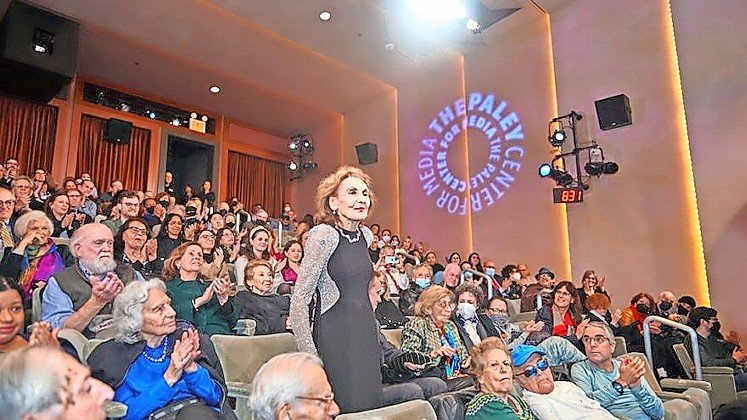

In honor of the 70-year anniversary of the signing of the agreement that paved the way for normalization between Germany and Israel and the Jewish world, Jewish-American director Roberta Grossman recounted the tense negotiations between the leaders in her recent film “Reckonings.”

The movie, which was recently screened at the Jerusalem Jewish Film Festival and in New York, includes testimonies by Holocaust survivors who agreed to receive reparations and those who did not, as well as by Jewish American lawyer Benjamin Ferencz, the last surviving participant in the negotiations and chief prosecutor for the United States Army at the Einsatzgruppen Trial, one of the 12 Subsequent Nuremberg Trials held by the US authorities at Nuremberg, Germany. It also includes testimonies by Adenauer’s grandson and Sharett’s son.

Grossman, whose family immigrated to the US before World War I, first became aware of the reparations issue when working on a documentary about the secret archives of the Warsaw Ghetto and when she received a grant for it from the Claims Conference.

The thing that amazed her the most in her work on Reckonings was discovering that the Israeli delegations and the Claims Conference were concerned about the identity of the German negotiators.

“They were very worried that they would find themselves negotiating with Nazi criminals,” Grossman said. “To a certain extent, this was the case, because they negotiated with a government that replaced the Nazi government. But the people they met were opponents of the Nazi regime. Many of the Israeli negotiators were German Jews, who immigrated to Israel before the war or after surviving it. At some point, one of them discovered that he had gone to the same school in Weimar where one of the German negotiators studied before the war.”

Q: Negotiating with Germany about war reparations a mere seven years after the end of the Holocaust was very complex.

“There was a lot of opposition,” Grossman stressed. “There was a significant part of Israel that was very opposed to negotiations with the Germans. They felt that it would be unconscionable to talk about money with the murderers. And some thought the opposite, that conscience should be put aside and something should be done to help the survivors. Tensions were running high not only in Israel but in many parts of the Jewish world. Survivors were divided between those who found a way to agree to receive money from the Germans and those who thought it was horrifying to even think that someone could receive money to somehow compensate for the murder of their parents, siblings, and relatives.

“Ultimately, the decision was to do something to help the survivors get back on their feet and to help Israel at a time of very severe economic distress, which could have led to the end of the State of Israel a few years after it was established.

“At the time, Israel was faced with very difficult economic consequences of the Independence War and the high costs of about 700,000 refugees who had come to Israel within the previous year or two, of which about 400,000 were Holocaust survivors. The number of refugees taken in was greater than the total population of Israel at the time. It was a very heavy economic burden, and Israel urgently needed financial aid.”

Q: Till today, some say that the agreement was struck too fast and too soon. Have you thought about whether it was the right decision?

“Of course, and I believe it was the right decision. There is no such thing as perfect. Adenauer was sincere in his desire to pay reparations as a form of apology, and he did his best to help. Obviously, he had realistic political considerations, chief among them the desire to regain the favor of the nations of the world. In the end, survivors who had no home, no parents, and no education, who were physically and emotionally broken, needed help, and also a certain kind of recognition and apology from Germany. Emotionally and financially, this agreement was important.”

Greg Schneider, vice president of the Claims Conference, noted that, contrary to popular belief, the payments were not “money for blood.”

“From the Jewish and Israeli point of view, the moral dilemma was related to sitting in the same room with the Germans only seven years after the liberation of the camps,” he explained. “Everything was still very fresh and full of emotions. The issue of looted property, as well as reparations for suffering and damage to health, were present in the negotiations. Although the negotiators themselves were not Nazis, the whole idea of sitting down with Germans and discussing reparations for survivors seven years after the Holocaust was difficult. It’s almost inconceivable that people from both sides would be able to sit in the same room together.

“Reckonings is also about the emotional journey of the survivors in receiving the money. The check they receive every month as compensation is a reminder of what they lost and what was taken from them. It is a very unique story about the Jewish people, but at the same time, it has a universal lesson. The idea that Jews could sit in one room with Germans in 1952 gives hope for reconciliation between groups that are in conflict. This is an important message in the dark times the world is experiencing today.”

Schneider explained that another misconception is that the agreement included a deadline for the payments.

“After all, the suffering of the survivors continues even today,” he continued. “It’s about helping to deal with the suffering — providing home and medical care, transportation, psychological help, and social programs. All of this is dealing with the consequences of the Holocaust, which are very present in the lives of the survivors.

“People who were 15 during the war and today are in their 90s suffering from nightmares about what happened to them in their youth. Some people suffer physically from what they experienced at that time or from the consequences of deprivation.

“The annual negotiations we still have with Germany are not about money. We talk about the status of the survivors, how many of them are still alive, what they went through, and how the German government can help them. As long as the suffering continues, the negotiations will continue, and the German government has agreed to this. We have differences of opinion on the size and nature of the aid, but at least today the German government accepts the concept that it must continue to help deal with the consequences of the Holocaust.

“In recent years there has been an understanding in Germany that this is the last stage of the reparations and the last chance to do the right thing. There is a new generation of government officials, who understand that they will be the ones to write the last words regarding the way Germany conducted itself on this issue of reparations, and this puts a lot of responsibility in their hands.”

To date, Germany has paid approximately 90 billion dollars in reparations to Holocaust survivors.

In Israel, opposition to the negotiations came from Right, Left and Center, said historian Jacob Tobi, researcher and lecturer at the University of Haifa, an expert in Israel-German ties. It was also opposed by non-political entities, like Holocaust survivor assocations and student groups, as well as news outlets like Maariv and Yediot Ahronoth.

“There was conscientious-principled-historical opposition to direct talks with the murderers so soon after the terrible event of the Holocaust,” Tobi said. “They saw this as a desecration of the memory of the millions who were murdered, a form of humiliation for the hundreds of thousands of Holocaust survivors who lived in Israel and abroad, a humiliation of Israel’s honor among the nations who saw how they ran to ask for money.”

In Begin’s case, “it also stemmed from his personal story, as his family perished in the Holocaust.”

Q: How did these parties react to the argument of the government at the time, that German aid was essential for the continued existence of the young state of Israel?

“Both camps, the one that opposed the negotiations and the one that supported it, had several main arguments, one of which stood out. For the government, the prominent argument was that the reparations would restore the State of Israel, allow it to exist and prevent a second Holocaust in the face of an existential threat from the Arab nations.

“The opposition claimed that the move would lead to reconciliation between Israel and West Germany, and that the entire moral-conscience establishment of boycotting Germany and the German people for generations following the most terrible crime in Jewish history would collapse and normalization would take place — which is what happened.

“When the opposition responded to the financial argument, it said that the Germans would not transfer the funds, claiming the German people were liars, so the government’s hope that the reparations would save the country was baseless. Another argument was that the Germans would not transfer goods to Israel in the quantity and quality required.

“Moreover, they claimed that as soon as Israel accepts the reparations agreements — if it accepts — it will lose financially from other sources. The US would stop helping Israel with loans, and world Jewry would not help either. It also claimed that the amount that Israel was demanding from the Germans did not at all reflect the loss caused to the Jewish people in the Holocaust. It is also claimed that the future moral damage as a result of these negotiations would have heavier consequences than not taking the funds.”

The negotiations were conducted and the agreement was struck with West Germany. But meanwhile, on the other side of the Berlin Wall, East Germany was ruled by a post-Soviet government, with which Israel did not negotiate reparations and to this day has not demanded from it its share of the payments.

According to Tobi, “East Germany was a branch of the USSR, which had no interest in East Germany paying reparations to Israel or the Jews. From 1950, Israel adopted a Western orientation, and Moscow did not want to help such a country receive economic aid from its own country. There was also disguised antisemitism among the communists, which did not contribute to the desire to give compensation money to the Jews. The USSR felt that it was the country that suffered the most in WWII, and therefore it should be the first to receive reparations. Moscow suspected that had East Germany agreed to pay reparations to Israel, other countries would follow suit with demands.

“When Israel sent letters to the four occupying powers and demanded reparations, the Soviet Union from the beginning refrained from responding or responded negatively. The Israeli Foreign Ministry decided to keep the demands vis-à-vis East Germany on the back burner since the West German course had begun to develop. In Israel, they came to the conclusion that if they tried to push East German matter, it would not yield results and might undermine efforts with West Germany.

“After the signing of the agreement with West Germany, Israel renewed its attempts with the East through various diplomatic channels, mainly through the USSR because there were no diplomatic relations between Israel and East Germany, but it did not yield success. In the late 1980s, there was an attempt to settle the matter, but it too failed. Some speculate that once united, Germany gave East Germany’s share of the reparations through the donation of the first two submarines that Israel received following the Gulf.”

Q: In hindsight, would you say Israel made the right choice?

“There were two worldviews: Ben-Gurion’s pragmatic and realistic approach and Begin’s emotional and value-based one. At a government meeting in 1951, then-Finance Minister Finance Eliezer Kaplan said, ‘We have fuel for one month.’ That is, after a month factories, agriculture, and the army could not be operated. In fact, there would be no state. To which Ben-Gurion replied, ‘We do not need to experience a second Holocaust, this time by the hands of the Arabs. We will take any help we can get to build the state.’

“Begin claimed, for his part, that a nation that does not remember its history has no future, and that this will be reflected in various aspects and will be translated into the attitude of the nations of the world toward Israel and the attitude of the country’s residents toward the state. He believed that the practical aspects would undermine the moral existence of the country and that this is no less serious than a danger of physical-economic existence.

“A Bank of Israel study said that it would have been possible to restore the country’s economy from its dire state in the early 1950s by raising more funds from world Jewry and the United States, further tightening the belt and adopting an even more assertive economic plan, but it would have taken more time. In my opinion, the only thing Israel lacked at that time was time.

“Arab countries were declaring day and night their intention for a second round of fighting set to destroy the Jewish state. Between the fear of being physically wiped out and the fear that the move against Germany would corrupt public morality, between the urgent and the predictable, the urgent was more important. But perhaps one can question the accelerated normalization that followed the reparations agreement.”

47.0°,

Fair

47.0°,

Fair