Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, acclaimed scholar who made the Talmud more accessible, niftar at 83

By Ben Harris, JTA

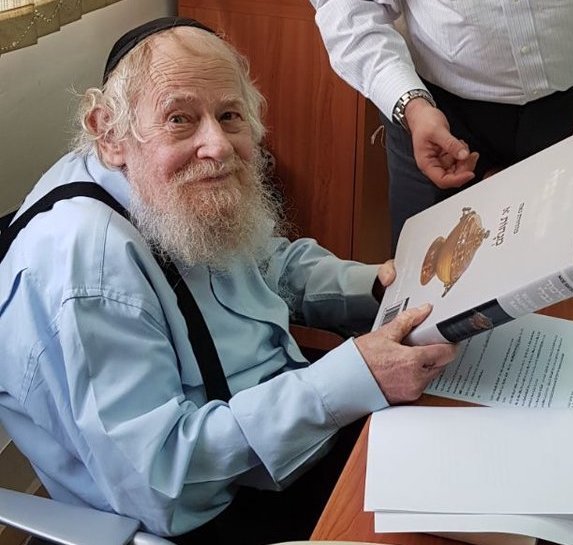

Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, the acclaimed scholar whose landmark translation of the Talmud enabled a vast readership to access one of Judaism’s most canonical texts, was niftar on Friday in Jerusalem. He was 83.

Rabbi Steinsaltz’s monumental translation of the 63 volumes of the Babylonian Talmud made the arcane rabbinic debates and folkloric tales easier to comprehend, unlocking the wonders of Talmud study for those lacking a high-level Jewish education. The project took 45 years to complete.

Rabbi Steinsaltz not only rendered the forbidding Aramaic text into modern Hebrew, but integrated his own commentary into the sparse language of the original, filling in gaps in the text that had previously required deep familiarity with the internal mechanics of talmudic discourse to decipher.

A new English version of the Steinsaltz Talmud by Koren publishing, and a free version of the translation available on the website Sefaria, further expanded Rabbi Steinsaltz’s reach.

“The Talmud was never meant to be an elitist book,” said Arthur Kurzweil, author of two books about Rabbi Steinsaltz and a board member of the Aleph Society, which raises funds to support the rabbi’s work. “It was meant to be for everybody. So Rabbi Steinsaltz spent 45 years trying and succeeding to make that happen.”

Authoring a comprehensive commentary on the Talmud alone put him in a category alongside Rashi, the medieval French scholar whose commentary on the Bible and the Talmud, composed 1,000 years ago, is considered the most authoritative. But Rabbi Steinsaltz, described as a once-in-a-millennium scholar, also wrote another 60 books on topics ranging from Jewish ethics to theology to prayer to mysticism. And he helped establish educational institutions in Israel and the former Soviet Union.

Born to secular parents in Jerusalem in 1937, he embraced Jewish practice as a teenager. Though his father was an irreligious socialist, he sent his son to study Talmud with a tutor at the age of 10. His gifts were evident early, when he became the youngest school principal in Israel at 23.

In 1965, Rabbi Steinsaltz founded the Israel Institute for Talmudic Publications, the same year he began his Talmud translation. His work was driven by a desire to educate large numbers of Jews about their heritage. “Let my people know,” was his favorite slogan.

“The Talmud is the central pillar of Jewish knowledge, important for the overall understanding of what is Jewish,” Rabbi Steinsaltz told JTA in 2010 on the occasion of the completion of the translation. “But it is a book that Jews cannot understand. This is a dangerous situation, like a collective amnesia. I tried to make pathways through which people will be able to enter the Talmud without encountering impassable barriers. It’s something that will always be a challenge, but I tried to make it at least possible.”

Rabbi Steinsaltz’s work was long deemed controversial. His Talmud departed from longstanding conventions, introducing punctuation and paragraph breaks, altering the pagination and placing his own commentary in the space around the main text that had previously been the domain of Rashi.

Rabbi Elazar Shach, a leading haredi rabbi in Israel, called Rabbi Steinsaltz a heretic and forbade his followers from reading his works, apparently out of concern for some passages in two works on the Bible that Rabbi Steinsaltz subsequently agreed to modify. Rabbi Shach insisted that all of Rabbi Steinsaltz’s work was heretical. Another eminent 20th-century authority, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, approved of the Steinsaltz Talmud.

Rabbi Steinsaltz was also criticized for accepting the leadership of a modern-day Sanhedrin, a recreation of the ancient rabbinic body. Rabbi Steinsaltz resigned the post in 2008 out of concern for potential breaches of Jewish law.

But none of that slowed Rabbi Steinsaltz’s embrace as an unparalleled scholar of Judaism, both in the Jewish world and beyond. He was awarded the Israel Prize, the Jewish state’s highest cultural honor, in 1998, along with the inaugural Israeli Presidential Award of Distinction, the French Order of Arts and Literature, and a 2012 National Jewish Book Award. He was invited to deliver the prestigious Terry Lectures at Yale University and was a scholar in residence at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington. In 2016, he was invited to a private audience with the pope.

Among his best-known works beyond the Talmud translation is “The Thirteen Petalled Rose,” an introduction to Jewish mysticism first published in 1980. A follower of the Chabad Hasidic movement, Rabbi Steinsaltz also authored several books on Tanya, one of the group’s core texts. In 2018, he published a translation and commentary on the Five Books of Moses.

Despite his massive intellectual achievements, Rabbi Steinsaltz often appeared slightly disheveled in public and had a playful streak. Kurzweil recalled an appearance at a Long Island yeshiva at which Rabbi Steinsaltz encouraged the students to do everything they could to make their teachers’ lives miserable, and even suggested a source book where they could find difficult questions sure to flummox them.

“He’s a troublemaker and he’s got a gleam in his eye at all times,” said Kurzweil, who served as Rabbi Steinsaltz’s driver during his visits to New York. “He likes to question everything.”

Long plagued by ill health, Rabbi Steinsaltz suffered a stroke in 2016 that left him unable to speak.

“Jewish learning is created by the Jews and is also creating the Jews,” Rabbi Steinsaltz said in 2010. “When you learn, you learn about yourself. So learning one page of the Talmud is equivalent to two or three sessions with a psychoanalyst. That’s why people are interested — Jewish learning is a mirror into our soul.”

Updated to reflect print edition version of this article.

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy