The Kosher Bookworm:The Exodus and the Emancipation

This past Tuesday, January 1st, 2013 we celebrated the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. This coming Shabbat and for the next month ahead, we will be reading and learning from Shemot, the Book of Exodus, the story of our slavery in Egypt and the subsequent liberation and the giving of the Ten Commandments.

Given the cold weather that we are experiencing, these spring season-like Torah readings bringing to mind Pesach and Shavuot, should be giving us some rather warm feelings, spiritually speaking. Thematically speaking, the slavery link between the Exodus of so long ago and the emancipation of black slaves 150 years ago brings together two very precious events in both world and religious history. This week’s essay will touch upon both, citing some relevant literary works for your learning pleasure.

One month before President Abraham Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, he sent to Congress his annual message. He ended that message, in anticipation of the proclamation, with the following stirring words:

“Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves….No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation. We say we are for the Union. The world will not forget that we say this. We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. We – even we here – hold the power, and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free – honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope on earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just – a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud, and G-d must forever bless.”

The use of the Almighty’s name in this document was to be followed up in a month, when it is cited once again in the conclusion to the Emancipation Proclamation:

“And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and gracious favor of Almighty G-d.”

According to historian Allen Guelzo in his book, “Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America,” this reference to G-d was no accident. And, indeed, the same claim is made by historian Louis Masur in his recently published “Lincoln’s Hundred Days: The Emancipation Proclamation and the War For The Union,” wherein he quotes from the New York Tribune that, “The President has been strongly pressed to place the Proclamation of Freedom upon high moral grounds.”

According to historian Harold Holzer in his recently published work, “Lincoln: How Abraham Lincoln Ended Slavery in America,” Lincoln told a visitor at that time, “No human power can subdue this rebellion without using the Emancipation lever as I have done.” In the president’s own words, the Emancipation proclamation was not only “the central act of my administration,” but also “the great event of the nineteenth century.”

Mazur points out Lincoln’s certainty of commitment, quoting the president as having said at that time that, “I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper … If my name goes down into history, it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”

Hopefully, this year there will be meaningful commemorations of this historic event to teach our youth the meaning of freedom and of the freeing of slaves, for we, too, were once slaves in the land of Egypt. And, that freedom is commemorated at this time of year in our weekly Torah readings.

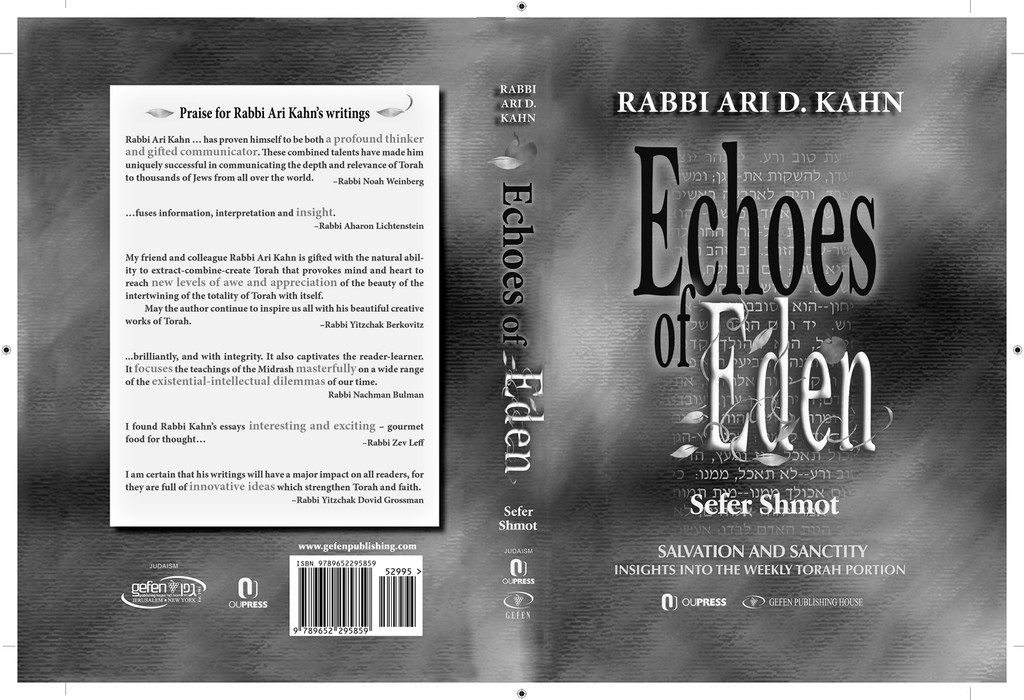

Freedom from slavery is given a very eloquent commentary in the recently published work, “Echoes of Eden: Sefer Shemot – Salvation and Sanctity” [OU Press / Gefen Publishing ,2012] by Rabbi Ari Kahn of Bar Ilan University.

Following the plague of the death of the first born, Paroh demands that the Jews leave immediately in the middle of the night.

According to Rabbi Kahn, “He pleads with them to leave, implores them to take the entire nation and go immediately. ‘Your are free, your are free!’ he shouts at them, but Moshe and Aharon retort: ‘Are we thieves that skulk about in the night? We will leave in the morning.’”

Rabbi Kahn continues with this observation that makes this moment even more significant than what the plain text appears to tell us.“The first act of freedom was choosing not to leave Egypt when Paroh told them to do so. G-d had commanded that no one was to leave their homes that night, and the nation exercised their right, as a free people, to obey the word of G-d and not the word of Paroh. They marched out of Egypt at the hour when the sun god was perceived to have been at the height of power. There would be no mistake about it: day or night, midnight or sunlight – Egyptian deities were powerless, meaningless. The Jews were set free when the firstborn were struck – at night, but they left Egypt the following morning, in broad daylight, with their heads held high, and the vanquished Egyptian gods no more than a memory.”

The Exodus experiences of our people served as an inspiration for those, some four thousand years later, to experience themselves, here in America. The very invocation of the Almighty in the Emancipation Proclamation 150 years ago this very week, serves as a testament to the everlasting faith that we Americans all share in the belief of a Higher Being who governs us all, and to the shared recognition of that fact, that will help sustain us all in the difficult times to come.

48.0°,

Light Rain

48.0°,

Light Rain