Sacred Spaces, in 5 Towns, promotes child safety

A resident of Squirrel Hill in Pittsburgh, where 11 people were killed and six others injured at the Tree of Life Congregation on Oct. 27, came to the Five Towns last week to speak on another painful topic.

Shira Berkovits, founder and chief executive officer of Sacred Spaces, still emotional after seeing her community targeted by an apparent anti-Semite, delved into child abuse in a presentation on Oct. 30, breaking down complex concepts into simple and easy-to-understand ideas and splicing Hebrew words into her Oct. 30 lecture. Sacred Spaces is a cross-denominational initiative to address institutional abuse in Jewish communities.

The meeting, at the Young Israel of Woodmere, was the Five Towns kickoff of Aleinu: A Safeguarding Children Campaign, which Sacred Spaces is spearheading, along with Congregation Sons of Israel, also in Woodmere, Hebrew Academy of Long Beach, Hebrew Academy of the Five Towns and Rockaway, the Hewlett-East Rockaway Jewish Centre, the Marion & Aaron Gural JCC, the Mid Island Y JCC, Ohel Children’s Home and Family Service, and the UJA-Federation of New York.

Noting recent programs in the Five Towns that have addressed children’s issues not previously discussed by the Orthodox Jewish community, including drug abuse, Rabbi Hershel Billet, of Young Israel, cited “a maturation of the Jewish community” for its efforts to begin discussing difficult topics. “Children should feel safe at home, safe at a synagogue, safe at school, camp and other programs where they need the protection of those who know that ill or evil people could take advantage of our children,” Billet said.

Berkovits acknowledged her uncertainty about leaving Squirrel Hill after the tragedy. She said a rabbi, Steven Exler, told her, “We honor their lives by protecting other lives.”

And many children need protection: Two-thirds of the sexual assaults committed nationwide target them, according to national statistics. Berkovits, who is also a lawyer, cited a 1998 Centers for Disease Control study that surveyed 17,000 adults, and found that before they turned 18, 28 percent suffered physical abuse, 25 percent endured neglect and 20 percent had been sexually assaulted. Subsequent studies found similar results, she said. “The impact is lasting — it doesn’t just go away,” Berkovits said. “There are psychological impacts, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicide, anxiety.”

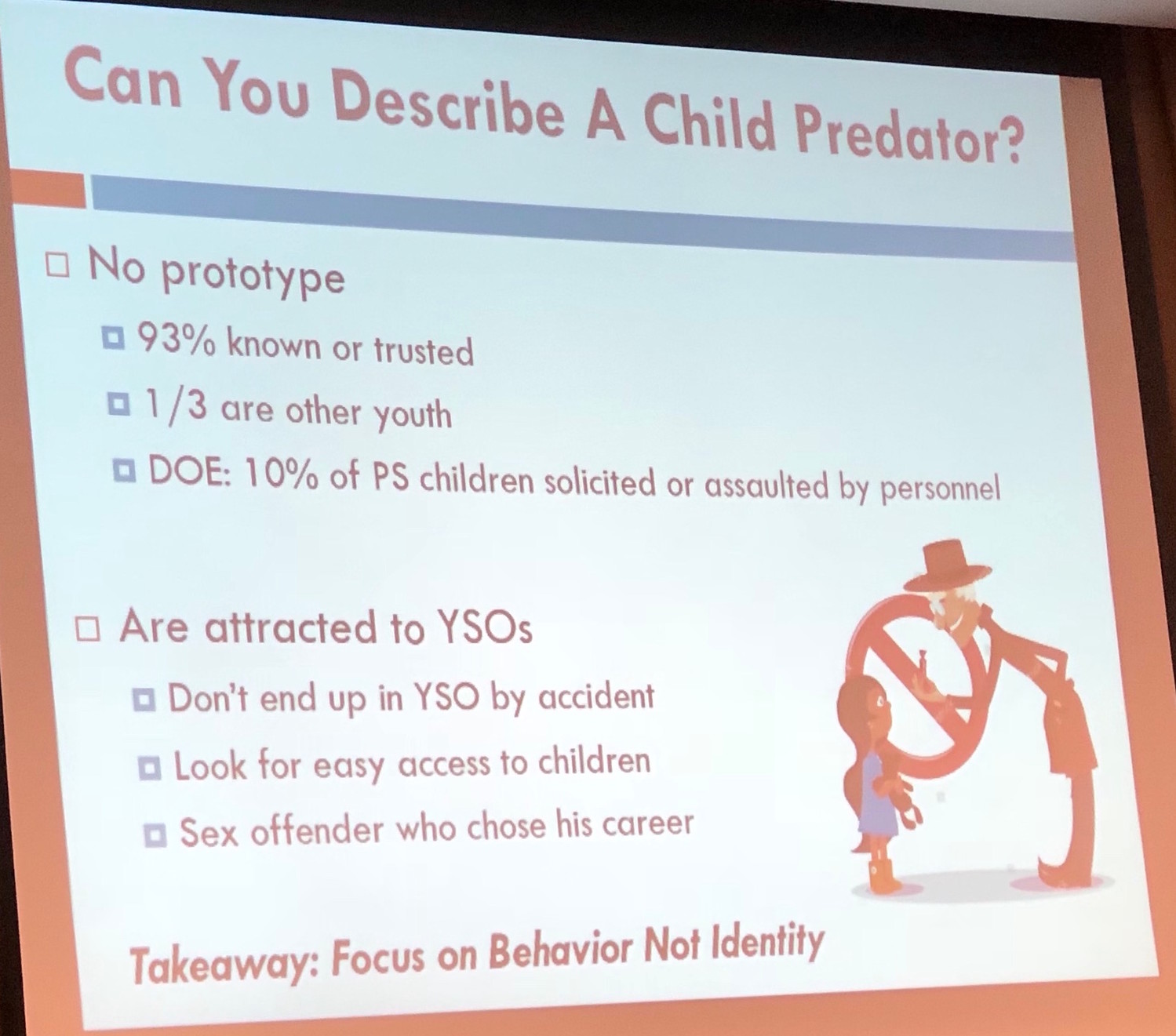

Spotting a child predator is not easy, because there is no known prototype, Berkovits noted, adding that 93 percent of predators are known or trusted by their victims, 33 percent are other young people and, according to the U.S. Department of Education, 10 percent of children in public schools have been solicited or assaulted by school personnel. “Child predators don’t end up in schools by accident,” she said, adding that they are also attracted to youth service organizations and summer camps.

Pointing to the sexual assault scandals involving the Catholic Church and Olympic gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar, Berkovits noted that incidents of abuse are often reported to different people who do not see a pattern or the entire picture. Her research led her to establish Sacred Spaces.

Elliot Pasik, an attorney from Long Beach and the father of six children, has been pushing for the fingerprinting of nonpublic-school employees for more than decade. Public schools in New York state are required to fingerprint employees as part of their background checks.

“There are persons with serious criminal histories who have tried getting jobs in both the public and nonpublic schools,” Pasik said. “Checking their criminal records keeps the schoolchildren out of harm’s way. Also, people with serious criminal histories who know they will be fingerprinted are deterred from applying for school employment.”

Of the 390 Jewish schools in the state, only two — North Shore High School in Great Neck and Shema Koleinu in Brooklyn — fingerprint employees. The New York State Association of Independent Schools recently mandated that its members fingerprint prospective employees, beginning this school year. Lawrence Woodmere Academy, in Woodmere, and North Shore are two of the 16 Long Island schools that are association members.

“Lawrence Woodmere Academy has been closely working with NYSIAS on the issue of fingerprinting requirements,” said LWA Headmaster Alan Bernstein. “NYSIAS is still reviewing a policy for existing employees, and has not yet made a decision on how member schools should begin to address that.” Bernstein said that fingerprinting each job applicant costs roughly $99.

An incident of sexual assault allegedly occurred recently at LWA. A former teacher at the school, Daniel McMenamin, of Valley Stream, was arrested on Oct. 18 and charged with multiple counts of sexual assault involving an underage girl who was a student at the school from November 2014, when she was 14, until July 2017, according to police.

Saying he takes the responsibility of keeping 450 boys and girls safe seriously, North Shore Headmaster Dr. Daniel Vitow said that is the reason his school fingerprints all prospective employees, from custodian to administrators, as part of the school’s background check. “I want to make sure that we’re working to maintain the maximum degree of safety and security,” Vitow said, adding that the policy has been in place for five years.

The Hebrew Academy of Long Beach, which includes HALB Elementary and DRS High School for Boys, both in Woodmere, SKA High School for Girls and Lev Chana Early Childhood Center, both in Hewlett Bay Park, and the Avnet summer day camp in Woodmere, does not fingerprint employees. “We do comprehensive background checks,” said Executive Director Richard Hagler.

Berkovits said that organizations and institutions must “decentralize power” and establish committees that will implement best practices to protect the children in their care. “What we are building has the ability to change the world,” she said.

Nearly all who attended the meeting were educators, social workers or youth group leaders. Michele Vernon, a senior vice president of Camp Sunrise, and Brielle Brook, the camp’s registrar, both said they benefited from Berkovits’s presentation. “It was concise and proactive on how we can take care of the children,” Vernon said.

“I liked that the institutions are working on this together,” Brooke added, “and we don’t have reinvent the wheel.”

49.0°,

Fair

49.0°,

Fair