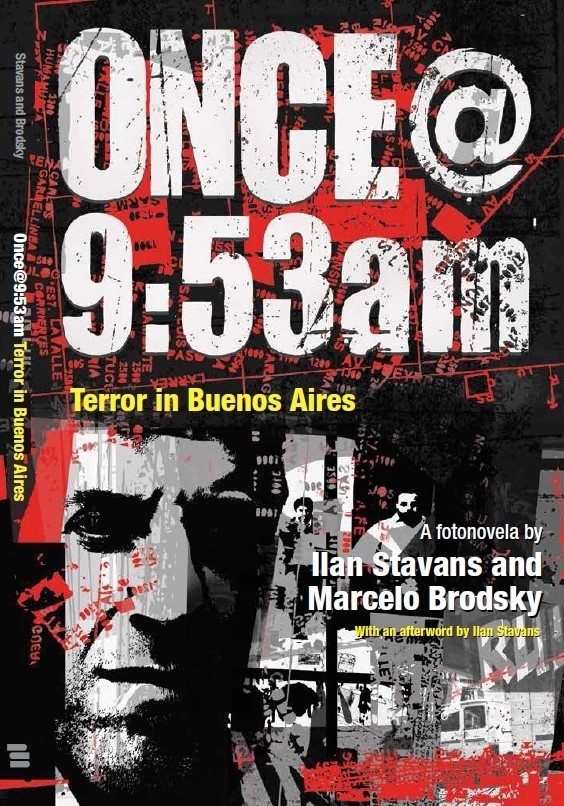

‘Fotonovela’ eyes Argentine Jewish center bombing

Do you know what a fotonovela is?

I didn’t either until I read “Once@9:53am: Terror in Buenos Aires,” a fascinating book that has renewed relevance, thanks to the recent reopening of an investigation into former Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s alleged covering up of Iran’s role in the bombing of the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA) Jewish center, an attack that killed 85 people and injured hundreds more.

The moment was 9:53 am on July l8, 1994, when a truck drove up to AMIA center, the major Jewish institution in Buenos Aires, and set off explosives. Nobody has been arrested for this crime, which is widely believed to have been perpetrated by Iranian-backed Hezbollah terrorists. The Jewish community and the people of Argentina have not yet recovered from the trauma of this awful event.

How do you describe what that day was like in words? Marcelo Brodsky, a talented photographer, and Ilan Stavans, a scholar of Latin-American Jewish life, enable us to understand what happened in a book that is part documentary, part chronicle and part fiction.

Minute by minute, Brodsky takes us through the three hours that led up to 9:53 that morning. El Once, the Buenos Aires neighborhood where the AMIA center was located, consisted of shops and rundown houses, something like what the East Side of Manhattan must have looked like a couple of generations ago. All kinds of ethnic groups lived side by side: Koreans, Poles, Peruvians, Armenians, Russians, Germans, Chinese and Jews. Even some ex-Nazis to whom the Juan Perón government gave a home in Argentina probably lived in El Once, bumping into their former victims on the crowded streets, with neither group ever acknowledging the other.

Brodsky takes his camera and walks the streets of El Once starting at 7 am, and reproduces what the neighborhood must have felt like that day. He enables us to watch as the stores open, as the blinds come down, as people hustle across the streets on their way to work, as life returns to the area after a night of quiet. He lets us listen in to the small talk that storekeepers, garbage collectors, customers and young people on their way to work exchange with each other as the day begins. To the average viewer, the people on the street seem to make up a faceless crowd, but Brodsky’s camera catches them in close-ups and enables us to see them as individuals: this one old, this one young, this one tense, this one happy, this one on the way to his yeshiva, this one on the way back from his night out.

We see these people stop and browse at the newspaper stands. All the front-page news is about yesterday’s soccer game, and nobody has any idea what’s about to happen will be tomorrow’s front-page news.

Brodsky sees a blonde woman dressed in a red suit, walking with three men who seem out of place, and for some reason he is attracted to her. He follows her, clicking away at her with his camera. She and the three men walking with her are annoyed that Brodsky is taking pictures of them, and they try to get away from him by darting in and out of some stores on the street, but he keeps pursuing them. Only three hours later will Brodsky realize who they are and why they are so eager to avoid him and his camera, but by then, it will be too late.

The photographer stops to schmooze with a young religious girl who is carrying some balloons, and he tries to explain what photography is all about. He tells her that he puts his eye behind the camera, and lets it carry him along, revealing the hidden treasures that it sees. He tells her sometimes he does not see the hidden treasures until he develops the film.

Throughout the morning, Brodsky keeps stopping to point his camera whenever he sees something significant. He has taken more than 200 pictures so far, but still does not know whether they add up to one coherent story or whether they are only records of casual encounters. He still keeps looking for the blonde woman and the three men, but they are nowhere to be seen.

At 9:32 am, they find him. The three young men jump him and beat him. They take his camera and throw it into the back of a garbage truck, and they run off, leaving him on the ground. At 9:53 am, the explosion goes off, and the world changes forever for those who are killed, for those who are wounded and for those who knew the victims.

The explosion smashed into the souls, if not into the bodies, of the loved ones of these casualties, into the hearts of people who live in Mexico, Miami, Moscow, Berlin, Tel Aviv and who knows where else. The fotonovela ends with these matter-of-fact words: “Eighty-five people died that day; more than 300 people were injured; the perpetrators were never captured; and the camera that saw the killers and that saw so much else that day remains lost.”

If that camera had not been lost, it might have identified the killers and led to their apprehension. Or, as Ilan Stavans makes clear in the afterword to this book, perhaps it would not have changed anything, because the Argentine government, politically and economically aligned with Iran, might not have looked at the pictures or cared about what they showed.

Nobody who reads this book will remain unaffected by the story that it tells. It gives a measure of immortality to those who died in the AMIA Jewish center attack that day. And it teaches us the enormous power of the camera to expose the truth.

When you read this book and look at these photographs, you cannot help but think of all the terrorist incidents that have occurred since that day in Buenos Aires. You think of Nice and of Berlin and now Jerusalem, where trucks hurtled down the streets killing innocent people who were in their path. You think of San Bernardino and of Orlando, where terrorists opened fire on people who were at an office party or at a nightclub. You think of Ankara, where the Russian ambassador was shot while dedicating an exhibit at an art gallery, or of Tel Aviv and many other places in Israel, where obscene acts like these have occurred so often—at bus stops and in cafés, at train stations and in airports. You realize this is a book that all of us need to read and study, so that we never get accustomed to atrocities and never take them for granted.

Jack Riemer is a prominent Conservative spiritual leader who has been referred to as President Bill Clinton’s rabbi.

69.0°,

A Few Clouds

69.0°,

A Few Clouds